As for the group known as the Essenes, though they are not mentioned in the Bible, nor for certain in the rabbinical literature, they are mentioned quite explicitly by Josephus and Philo. From these sources the Essenes appear to have been formed in small communities leading a religious and communistic on the shores of the Dead Sea. They were organized in several grades and formed a closely knit brotherhood.

The Essenes attached great importance to purity of life, practiced daily lustration and rejected animal sacrifices. Ultimately, the Essenes were a small Jewish order of about four thousand individuals who comprised a league of virtue. With their agricultural settlements, their quaint semi-ascetic practices, their strict novitiate, their silent meals, their white robes, their baths, their prayers, their simple but stringent socialism, their sacerdotal puritanism, their soothsaying, their passion for the mystical world of angels, their indifference to Messianic and nationalistic hopes, their esoteric beliefs, and their approximation to sacramental religion make it highly unlikely that the Essenes influenced early Christianity in any appreciable degree.

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Essenes, Essenians אִסִּיִים | |

|---|---|

| Historical leader | |

| Founded | 2nd century BCE |

| Dissolved | 1st century CE |

| Headquarters | Qumran (proposed)[1] |

| Ideology | |

| Religion | Judaism |

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Essene, member of a religious sect or brotherhood that flourished in Palestine from about the 2nd century bc to the end of the 1st century ad. The New Testament does not mention them and accounts given by Josephus, Philo of Alexandria, and Pliny the Elder sometimes differ in significant details, perhaps indicating a diversity that existed among the Essenes themselves.

The Essenes clustered in monastic communities that, generally at least, excluded women. Property was held in common and all details of daily life were regulated by officials. The Essenes were never numerous; Pliny fixed their number at some 4,000 in his day.

Like the Pharisees, the Essenes meticulously observed the Law of Moses, the sabbath, and ritual purity. They also professed belief in immortality and divine punishment for sin. But, unlike the Pharisees, the Essenes denied the resurrection of the body and refused to immerse themselves in public life. With few exceptions, they shunned Temple worship and were content to live ascetic lives of manual labour in seclusion. The sabbath was reserved for day-long prayer and meditation on the Torah (first five books of the Bible). Oaths were frowned upon, but once taken they could not be rescinded.

After a year’s probation, proselytes received their Essenian emblems but could not participate in common meals for two more years. Those who qualified for membership were called upon to swear piety to God, justice toward men, hatred of falsehood, love of truth, and faithful observance of all other tenets of the Essene sect. Thereafter new converts were allowed to take their noon and evening meals in silence with the others.

Following the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls (late 1940s and 1950s) in the vicinity of Khirbat Qumrān, most scholars have agreed that the Qumrān (q.v.) community was Essenian.

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

The Essenes (/ˈɛsiːnz, ɛˈsiːnz/; Hebrew: אִסִּיִים, ʾĪssīyīm; Greek: Ἐσσηνοί, Ἐσσαῖοι, or Ὀσσαῖοι, Essenoi, Essaioi, Ossaioi) or Essenians were a mystic Jewish sect during the Second Temple period that flourished from the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century CE.[2]

The Essene movement likely originated as a distinct group among Jews during Jonathan Apphus' time, driven by disputes over Jewish law and the belief that Jonathan's high priesthood was illegitimate.[3] Most scholars think the Essenes seceded from the Zadokite priests.[4] They attributed their interpretation of the Torah to their early leader, the Teacher of Righteousness, possibly a legitimate high priest. Embracing a conservative approach to Jewish law, they observed a strict hierarchy favoring priests (the Sons of Zadok) over laypeople, emphasized ritual purity, and held a dualistic worldview.[3]

According to Jewish writers Josephus and Philo, the Essenes numbered around four thousand, and resided in various settlements throughout Judaea. Conversely, Roman writer Pliny the Elder positioned them somewhere above Ein Gedi, on the west side of the Dead Sea.[5][6] Pliny relates in a few lines that the Essenes possess no money, had existed for thousands of generations, and that their priestly class ("contemplatives") did not marry. Josephus gave a detailed account of the Essenes in The Jewish War (c. 75 CE), with a shorter description in Antiquities of the Jews (c. 94 CE) and The Life of Flavius Josephus (c. 97 CE). Claiming firsthand knowledge, he lists the Essenoi as one of the three sects of Jewish philosophy[7] alongside the Pharisees and Sadducees. He relates the same information concerning piety, celibacy; the absence of personal property and of money; the belief in communality; and commitment to a strict observance of Sabbath. He further adds that the Essenes ritually immersed in water every morning (a practice similar to the use of the mikveh for daily immersion found among some contemporary Hasidim), ate together after prayer, devoted themselves to charity and benevolence, forbade the expression of anger, studied the books of the elders, preserved secrets, and were very mindful of the names of the angels kept in their sacred writings.

The Essenes have gained fame in modern times as a result of the discovery of an extensive group of religious documents known as the Dead Sea Scrolls, which are commonly believed to be the Essenes' library. The scrolls were found at Qumran, an archaeological site situated along the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea, believed to have been the dwelling place of an Essene community. These documents preserve multiple copies of parts of the Hebrew Bible along with deuterocanonical and sectarian manuscripts, including writings such as the Community Rule, the Damascus Document, and the War Scroll, which provide valuable insights into the communal life, ideology and theology of the Essenes.

According to the conventional view, the Essenes disappeared after the First Jewish–Roman War, which also witnessed the destruction of the settlement at Qumran.[3] Scholars have noted the absence of direct sources supporting this claim, raising the possibility of their endurance or the survival of related groups in the following centuries.[8] Some researchers suggest that Essene teachings could have influenced other religious traditions, such as Mandaeism and Jewish Christianity.[9][10]

Etymology

[edit]Josephus uses the name Essenes in his two main accounts, The Jewish War 2.119, 158, 160 and Antiquities of the Jews, 13.171–2, but some manuscripts read here Essaion ("holding the Essenes in honour";[11] "a certain Essene named Manaemus";[12] "to hold all Essenes in honor";[13] "the Essenes").[14][15][16]

In several places, however, Josephus has Essaios, which is usually assumed to mean Essene ("Judas of the Essaios race";[17] "Simon of the Essaios race";[18] "John the Essaios";[19] "those who are called by us Essaioi";[20] "Simon a man of the Essaios race").[21] Josephus identified the Essenes as one of the three major Jewish sects of that period.[22]

Philo's usage is Essaioi, although he admits this Greek form of the original name, that according to his etymology signifies "holiness", to be inexact.[23] Pliny's Latin text has Esseni.[5][24]

Gabriele Boccaccini implies that a convincing etymology for the name Essene has not been found, but that the term applies to a larger group within Judea that also included the Qumran community.[25]

It was proposed before the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered that the name came into several Greek spellings from a Hebrew self-designation later found in some Dead Sea Scrolls, ʻosey haTorah, "'doers' or 'makers' of Torah".[26] Although dozens of etymology suggestions have been published, this is the only etymology published before 1947 that was confirmed by Qumran text self-designation references, and it is gaining acceptance among scholars.[27] It is recognized as the etymology of the form Ossaioi (and note that Philo also offered an O spelling) and Essaioi and Esseni spelling variations have been discussed by VanderKam, Goranson, and others. In medieval Hebrew (e.g., Sefer Yosippon) Hassidim "the Pious" replaces "Essenes". While this Hebrew name is not the etymology of Essaioi/Esseni, the Aramaic equivalent Hesi'im known from Eastern Aramaic texts has been suggested.[28] Others suggest that Essene is a transliteration of the Hebrew word ḥiṣonim (ḥiṣon "outside"), which the Mishnah (e.g., Megillah 4:8[29]) uses to describe various sectarian groups. Another theory is that the name was borrowed from a cult of devotees to Artemis in Anatolia, whose demeanor and dress somewhat resembled those of the group in Judea.[30]

Flavius Josephus in Chapter 8 of "The Jewish War" states:

Location

[edit]

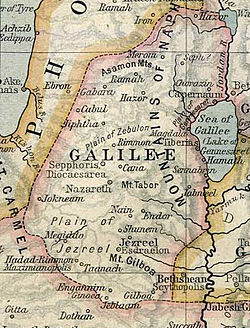

According to Josephus, the Essenes had settled "not in one city" but "in large numbers in every town".[32] Philo speaks of "more than four thousand" Essaioi living in "Palestine and Syria",[33] more precisely, "in many cities of Judaea and in many villages and grouped in great societies of many members".[34]

Pliny locates them "on the west side of the Dead Sea, away from the coast... [above] the town of Engeda".[24]

Some modern scholars and archeologists have argued that Essenes inhabited the settlement at Qumran, a plateau in the Judean Desert along the Dead Sea, citing Pliny the Elder in support and giving credence that the Dead Sea Scrolls are the product of the Essenes.[35] This theory, though not yet conclusively proven, has come to dominate the scholarly discussion and public perception of the Essenes.[36]

Rules, customs, theology, and beliefs

[edit]The accounts by Josephus and Philo show that the Essenes led a strictly communal life—often compared to later Christian monasticism.[37] Many of the Essene groups appear to have been celibate, but Josephus speaks also of another "order of Essenes" that observed the practice of being engaged for three years and then becoming married.[38] According to Josephus, they had customs and observances such as collective ownership,[39][40] electing a leader to attend to the interests of the group, and obedience to the orders from their leader.[41] Also, they were forbidden from swearing oaths[42] and from sacrificing animals.[43] They controlled their tempers and served as channels of peace,[42] carrying weapons only for protection against robbers.[44] The Essenes chose not to possess slaves but served each other[45] and, as a result of communal ownership, did not engage in trading.[46] Josephus and Philo provide lengthy accounts of their communal meetings, meals, and religious celebrations. This communal living has led some scholars to view the Essenes as a group practicing social and material egalitarianism.[47][48][49]

Despite their prohibition on swearing oaths, after a three-year probationary period,[50] new members would take an oath that included a commitment to practice piety to God and righteousness toward humanity; maintain a pure lifestyle; abstain from criminal and immoral activities; transmit their rules uncorrupted; and preserve the books of the Essenes and the names of the angels.[51] Their theology included belief in the immortality of the soul and that they would receive their souls back after death.[15][52] Part of their activities included purification by water rituals which was supported by rainwater catchment and storage. According to the Community Rule, repentance was a prerequisite to water purification.[53]

Ritual purification was a common practice among the peoples of Judea during this period and was thus not specific to the Essenes. A ritual bath or mikveh was found near many synagogues of the period continuing into modern times.[54] Purity and cleanliness was considered so important to the Essenes that they would refrain from defecation on the Sabbath.[55]

According to Joseph Lightfoot, the Church Father Epiphanius (writing in the 4th century CE) seems to make a distinction between two main groups within the Essenes:[28] "Of those that came before his [Elxai, an Ossaean prophet] time and during it, the Ossaeans and the Nasaraeans." Part 18[56] Epiphanius describes each group as following:

We do not know much about the canon of the Essenes, and what their attitude was towards the apocryphal writings, however the Essenes perhaps did not esteem the book of Esther highly as manuscripts of Esther are completely absent in Qumran, likely because of their opposition to mixed marriages and the use of different calendars.[58][59]

The Essenes were unique for their time for being against the practice of slave-ownership, and slavery, which they regarded as unjust and ungodly, regarding all men as having been born equal.[60][61]

Involvement in the First Jewish–Roman War

[edit]At the outset of the First Jewish–Roman War in 66 CE, as Roman advances were anticipated, command over parts of western Judea was assigned to John the Essene (or Essaean), who was placed in charge of the toparchy of Thamna. This region encompassed Lydda, Joppa, and Emmaus.[62]

Scholarly discussion

[edit]Josephus and Philo discuss the Essenes in detail. Most scholars[citation needed] believe that the community at Qumran that most likely produced the Dead Sea Scrolls was an offshoot of the Essenes. However, this theory has been disputed by some; for example, Norman Golb argues that the primary research on the Qumran documents and ruins (by Father Roland de Vaux, from the École Biblique et Archéologique de Jérusalem) lacked scientific method, and drew wrong conclusions that comfortably entered the academic canon. For Golb, the number of documents is too extensive and includes many different writing styles and calligraphies; the ruins seem to have been a fortress, used as a military base for a very long period of time—including the 1st century—so they therefore could not have been inhabited by the Essenes; and the large graveyard excavated in 1870, just 50 metres (160 ft) east of the Qumran ruins, was made of over 1200 tombs that included many women and children; Pliny clearly wrote that the Essenes who lived near the Dead Sea "had not one woman, had renounced all pleasure... and no one was born in their race". Golb's book presents observations about de Vaux's premature conclusions and their uncontroverted acceptance by the general academic community. He states that the documents probably stemmed from various libraries in Jerusalem, kept safe in the desert from the Roman invasions.[63] Other scholars refute these arguments—particularly since Josephus describes some Essenes as allowing marriage.[64]

Another issue is the relationship between the Essaioi and Philo's Therapeutae and Therapeutrides. He regarded the Therapeutae as a contemplative branch of the Essaioi who, he said, pursued an active life.[65]

One theory on the formation of the Essenes suggests that the movement was founded by a Jewish high priest, dubbed by the Essenes the Teacher of Righteousness, whose office had been usurped by Jonathan (of priestly but not of Zadokite lineage), labeled the "man of lies" or "false priest".[66][67][unreliable source?] Others follow this line and a few argue that the Teacher of Righteousness was not only the leader of the Essenes at Qumran, but was also identical to the original Messianic figure about 150 years before the time of the Gospels.[36] Fred Gladstone Bratton notes that

Lawrence Schiffman has argued that the Qumran community may be called Sadducean, and not Essene, since their legal positions retain a link with Sadducean tradition.[69]

Connection to other religious traditions

[edit]Mandaeism

[edit]

The Haran Gawaita uses the name Nasoraeans for the Mandaeans arriving from Jerusalem, meaning guardians or possessors of secret rites and knowledge.[70] Scholars such as Kurt Rudolph, Rudolf Macúch, Mark Lidzbarski and Ethel S. Drower connect the Mandaeans with the Nasaraeans described by Epiphanius, a group within the Essenes according to Joseph Lightfoot.[71][72]: xiv [73][74][75][76][28] Epiphanius (29:6) says that they existed before Jesus. That is questioned by some, but others accept the pre-Christian origin of the Nasaraeans.[72]: xiv [77]

Early religious concepts and terminologies recur in the Dead Sea Scrolls, and Yardena (Jordan) has been the name of every baptismal water in Mandaeism.[78]: 5 Mara ḏ-Rabuta (Mandaic for 'Lord of Greatness', which is One of the names for the Mandaean God Hayyi Rabbi) is found in the Genesis Apocryphon II, 4.[79]: 552–553 Another early self-appellation is bhiria zidqa, meaning 'elect of righteousness' or 'the chosen righteous', a term found in the Book of Enoch and Genesis Apocryphon II, 4.[79]: 552–553 [70][80]: 18 [81] As Nasoraeans, Mandaeans believe that they constitute the true congregation of bnia nhura, meaning 'Sons of Light', a term used by the Essenes.[82]: 50 [83] Mandaean scripture affirms that the Mandaeans descend directly from John the Baptist's original Nasoraean Mandaean disciples in Jerusalem.[84]: vi, ix Similar to the Essenes, it is forbidden for a Mandaean to reveal the names of the angels to a gentile.[85]: 94 Essene graves are oriented north–south[86] and a Mandaean's grave must also be in the north–south direction so that if the dead Mandaean were stood upright, they would face north.[85]: 184 Mandaeans have an oral tradition that some were originally vegetarian[72]: 32 and also similar to the Essenes, they are pacifists.[87]: 47 [88]

The bit manda (beth manda) is described as biniana rba ḏ-šrara ("the Great building of Truth") and bit tušlima ("house of Perfection") in Mandaean texts such as the Qulasta, Ginza Rabba, and the Mandaean Book of John. The only known literary parallels are in Essene texts from Qumran such as the Community Rule, which has similar phrases such as the "house of Perfection and Truth in Israel" (Community Rule 1QS VIII 9) and "house of Truth in Israel."[89]

Christianity

[edit]

Rituals of the Essenes and Christianity have much in common; the Dead Sea Scrolls describe a meal of bread and wine that will be instituted by the messiah, both the Essenes and Christians were eschatological communities, where judgement on the world would come at any time.[91] The New Testament also possibly quotes writings used by the Qumran community. Luke 1:31-35 states " And now you will conceive in your womb and bear a son and you will name him Jesus. He will be great and will be called the son of the Most High...the son of God" which seems to echo 4Q 246, stating: "He will be called great and he will be called Son of God, and they will call him Son of the Most High...He will judge the earth in righteousness...and every nation will bow down to him".[91]

Other similarities include high devotion to the faith even to the point of martyrdom, communal prayer, self denial and a belief in a captivity in a sinful world.[92]

John the Baptist has also been argued to have been an Essene, as there are numerous parallels between John's mission and the Essenes, which suggests he perhaps was trained by the Essene community.[90]

In the early church a book called the Odes of Solomon was written. The writer was likely a very early convert from the Essene community into Christianity. The book reflects a mixture of mystical ideas of the Essene community with Christian concepts.[93]

Both the Essenes and Christians practiced voluntary celibacy and prohibited divorce.[94] Both also used concepts of "light" and "darkness" for good and evil.[95]

A few have claimed that the Essenes had an idea of a pierced Messiah based on 4Q285; however, the interpretation of the text is ambiguous. Some scholars interpreted it as the Messiah being killed himself, while modern scholars mostly interpret it as the Messiah executing the enemies of Israel in an eschatological war.[96]

Both the Essenes and Christians practiced a ritual of immersion by water, however the Essenes had it as a regular practice instead of a one time event.[10]

Magarites

[edit]The Magharians or Magarites (Arabic: Al-Maghariyyah, 'people of the caves')[97] were, according to Jacob Qirqisani, a Jewish sect founded in the 1st century BCE. Abraham Harkavy and others identify the Magharians with the Essenes, and their author referred to as the "Alexandrinian" with Philo (whose affinity for the Essenes is well-known), based on the following evidence:[97][98]

- The sect's name, which, in his view, does not refer to its books but to its followers who lived in caves or desert areas—an established Essene lifestyle;

- The sect's founding date coinciding with that of the Essenes;

- The theory that God interacts with humans through an angel aligning with Essene beliefs, as well as Philo's concept of the Logos;

- Qirqisani's omission of the Essenes from his list of Jewish sects, which can be explained if he considered the Magharians to be synonymous with the Essenes.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ אשל, חנן, "תולדות התגליות הארכאולוגיות בקומראן", בתוך: מנחם קיסטר (עורך), מגילות קומראן: מבואות ומחקרים, כרך א', ירושלים: יד יצחק בן-צבי. 2009, עמ' 9. (Hebrew)

- ^ Cyprus), Saint Epiphanius (Bishop of Constantia in (2009). The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis: Book I (sects 1-46). BRILL. p. 32. ISBN 978-90-04-17017-9.

- ^ a b c Gurtner, Daniel M.; Stuckenbruck, Loren T., eds. (2020). T&T Clark Encyclopedia of Second Temple Judaism. Vol. 2. T&T Clark. pp. 250–252. ISBN 978-0-567-66144-9.

- ^ F.F. Bruce, Second Thoughts on the Dead Sea Scrolls. Paternoster Press, 1956.

- ^ a b Pliny the Elder. Historia Naturalis. Vol. V, 17 or 29, in other editions V, (15).73.

Ab occidente litora Esseni fugiunt usque qua nocent, gens sola et in toto orbe praeter ceteras mira, sine ulla femina, omni venere abdicata, sine pecunia, socia palmarum. in diem ex aequo convenarum turba renascitur, large frequentantibus quos vita fessos ad mores eorum fortuna fluctibus agit. ita per saeculorum milia—incredibile dictu—gens aeterna est, in qua nemo nascitur. tam fecunda illis aliorum vitae paenitentia est! infra hos Engada oppidum fuit, secundum ab Hierosolymis fertilitate palmetorumque nemoribus, nunc alterum bustum. inde Masada castellum in rupe, et ipsum haut procul Asphaltite. et hactenus Iudaea est.

cf. English translation. - ^ Barthélemy, D.; Milik, J.T.; de Vaux, Roland; Crowfoot, G.M.; Plenderleith, Harold; Harding, G.L. (1997) [1955]. "Introductory: The Discovery". Qumran Cave 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-19-826301-5. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ^ Josephus (c. 75). The Wars of the Jews. 2.119.

- ^ Goodman, M. (1994), "Sadducees and Essenes after 70 CE", Judaism in the Roman World, Brill, pp. 153–162, doi:10.1163/ej.9789004153097.i-275.38, ISBN 978-90-474-1061-4, retrieved 2 August 2023

- ^ Hamidović, David (2010). "About the Links between the Dead Sea Scrolls and Mandaean Liturgy". ARAM Periodical. 22: 441–451. doi:10.2143/ARAM.22.0.2131048.

- ^ a b Charlesworth, James H. (2006). The Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls: The scrolls and Christian origins. Baylor University Press. ISBN 978-1-932792-21-8.

- ^ Josephus (c. 94). Antiquities of the Jews. 15.372.

- ^ Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 15.373.

- ^ Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 15.378.

- ^ Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 18.11.

- ^ a b Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 18.18.

- ^ Josephus. The Life of Flavius Josephus. 10.

- ^ Josephus. The Wars of the Jews. I.78.

- ^ Josephus. The Wars of the Jews. 2.113.

- ^ Josephus. The Wars of the Jews. 2.567; 3.11.

- ^ Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 15.371.

- ^ Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 17.346.

- ^ And when I was about sixteen years old, I had a mind to make trial of the several sects that were among us. These sects are three: The first is that of the Pharisees, the second that Sadducees, and the third that of the Essenes, as we have frequently told you The Life of Josephus Flavius, 2.

- ^ Philo. Quod Omnis Probus Liber. XII.75–87.

- ^ a b Pliny the Elder. Natural History. 5.73.

- ^ Boccaccini, Gabriele (1998). Beyond the Essene hypothesis: the parting of the ways between Qumran and Enochic Judaism. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 47. ISBN 0-8028-4360-3. OCLC 37837643.

- ^ Goranson, Stephen (1999). "Others and Intra-Jewish Polemic as Reflected in Qumran Texts". In Peter W. Flint; James C. VanderKam (eds.). The Dead Sea Scrolls after Fifty Years: A Comprehensive Assessment. Vol. 2. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 534–551. ISBN 90-04-11061-5. OCLC 230716707.

- ^ For example, James C. VanderKam, "Identity and History of the Community". In The Dead Sea Scrolls after Fifty Years: A Comprehensive Assessment, ed. Peter W. Flint and James C. VanderKam, 2:487–533. Leiden: Brill, 1999. The earliest known proposer of this etymology was P. Melanchthon, in Johann Carion, Chronica, 1532, folio 68 verso. Among the other proposers before 1947, e.g., 1839 Isaak Jost, "Die Essaer," Israelitische Annalen 19, 145–7.

- ^ a b c Lightfoot, Joseph Barber (1875). "On Some Points Connected with the Essenes". St. Paul's epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon: a revised text with introductions, notes, and dissertations. London: Macmillan Publishers. OCLC 6150927.

- ^ "Mishnah Megillah 4:8". sefaria.org. Sefaria.

- ^ Schiffman, Lawrence H. (27 July 2015). "Discovery and Acquisition, 1947–1956, Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish Publication Society, Philadelphia, 1994". Center for Online Judaic Studies. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Whiston and Maier, 1999, "The Jewish War", Chapter 8, p. 736

- ^ Josephus (c. 75). The Wars of the Jews. 2.124.

- ^ Philo (c. 20–54). Quod Omnis Probus Liber. XII.75.

- ^ Philo. Hypothetica. 11.1. in Eusebius. Praeparatio Evangelica. VIII.

- ^ Biblical Archeology Society Staff (8 May 2022). "Who Were the Essenes?". Biblical Archaeology Society. Biblical Archeology Society. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ a b Ellegård, Alvar; Jesus—One Hundred Years Before Christ: A Study in Creative Mythology, (London 1999).

- ^ The suggestion apparently goes back to Flinders Petrie's Personal religion in Egypt before Christianity (1909), 62ff; see William Herbert Mackean, Christian Monasticism in Egypt to the Close of the Fourth Century (1920), p. 18.

- ^ Josephus (c. 75). The Wars of the Jews. book II, chap. 8, para. 13.

- ^ Josephus (c. 75). The Wars of the Jews. 2.122.

- ^ Josephus (c. 94). Antiquities of the Jews. 18.20.

- ^ Josephus (c. 75). The Wars of the Jews. 2.123, 134.

- ^ a b Josephus (c. 75). The Wars of the Jews. 2.135.

- ^ Philo, §75: ου ζωα καταθυοντες [= not sacrificing animals]

- ^ Josephus (c. 75). The Wars of the Jews. 2.125.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Every Good Man is Free, 75-79.

- ^ Josephus (c. 75). The Wars of the Jews. 2.127.

- ^ Service, Robert (2007). Comrades: A History of World Communism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0674046993.

- ^ "Essenes". Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Kaufmann Kohler (1906). "Jewish Encyclopedia - Essenes".

- ^ Josephus (c. 75). The Wars of the Jews. 2.137–138. Josephus' mention of the three-year duration of the Essene probation may be compared with the phased character of the entrance procedure in the Qumran Rule of the Community [1QS; at least two years plus an indeterminate initial catechetical phase, 1QS VI]. The provisional surrender of property required at the beginning of the last year of the novitiate derives from actual social experience of the difficulties of sharing property in a fully communitarian setting, cf. Brian J. Capper, 'The Interpretation of Acts 5.4', Journal for the Study of the New Testament 19 (1983) pp. 117–131; idem, '"In der Hand des Ananias." Erwägungen zu 1QS VI,20 und der urchristlichen Gütergemeinschaft', Revue de Qumran 12(1986) 223–236; Eyal Regev, "Comparing Sectarian Practice and Organization: The Qumran Sect in Light of the Regulations of the Shakers, Hutterites, Mennonites and Amish", Numen 51 (2004), pp. 146–181.

- ^ Josephus (c. 75). The Wars of the Jews. 2.139–142.

- ^ Josephus (c. 75). The Wars of the Jews. 2.153–158.

- ^ Furstenberg, Yair (8 November 2016). "Initiation and the Ritual Purification from Sin: Between Qumran and the Apostolic Tradition". Dead Sea Discoveries. 23 (3): 365–394. doi:10.1163/15685179-12341409.

- ^ Kittle, Gerhardt. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, Volume 7. p. 814, note 99.

- ^ Dundes, A. (2002). The Shabbat Elevator and other Sabbath Subterfuges: An Unorthodox Essay on Circumventing Custom and Jewish Character. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 109. ISBN 9781461645603. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ a b Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 378). Panarion. 1:19.

- ^ Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 378). Panarion. 1:18.

- ^ Mulder, Martin-Jan (1 January 1988). The Literature of the Jewish People in the Period of the Second Temple and the Talmud, Volume 1 Mikra: Text, Translation, Reading and Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-27510-2.

- ^ Fitzmyer, Joseph A. (2009). The Impact of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-4615-4.

- ^ Lim, Timothy (2021). Essenes in Judaean Society: The sectarians of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Oxford University Press's Academic Insights for the Thinking World.

- ^ "Essenes in Judaean Society: The sectarians of the Dead Sea Scrolls". 17 January 2021.

- ^ Rogers, Guy MacLean (2021). For the Freedom of Zion: the Great Revolt of Jews against Romans, 66-74 CE. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-300-24813-5.

- ^ Golb, Norman (1996). Who wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls?: the search for the secret of Qumran. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80692-4. OCLC 35047608.[page needed]

- ^ Josephus, Flavius. Jewish War, Book II. Chapter 8, Paragraph 13.

- ^ Philo. De Vita Contemplativa. I.1.

- ^ McGirk, Tim (16 March 2009). "Scholar Claims Dead Sea Scrolls 'Authors' Never Existed". Time. Archived from the original on 20 March 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ^ "Rachel Elior Responds to Her Critics". Jim West. 15 March 2009. Archived from the original on 21 March 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ^ Bratton, Fred Gladstone. 1967. A History of the Bible. Boston: Beacon Press, 79-80.

- ^ James VanderKam and Peter Flint, The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls, p. 251.

- ^ a b Rudolph, Kurt (7 April 2008). "Mandaeans ii. The Mandaean Religion". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ Lidzbarski, Mark, Ginza, der Schatz, oder das Grosse Buch der Mandaer, Leipzig, 1925

- ^ a b c Drower, Ethel Stephana (1960). The secret Adam, a study of Nasoraean gnosis (PDF). London UK: Clarendon Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2014.

- ^ Rudolph 1977, p. 4.

- ^ Thomas, Richard (29 January 2016). "The Israelite Origins of the Mandaean People". Studia Antiqua. 5 (2).

- ^ Macuch, Rudolf A Mandaic Dictionary (with E. S. Drower). Oxford: Clarendon Press 1963.

- ^ R. Macuch, "Anfänge der Mandäer. Versuch eines geschichtliches Bildes bis zur früh-islamischen Zeit", chap. 6 of F. Altheim and R. Stiehl, Die Araber in der alten Welt II: Bis zur Reichstrennung, Berlin, 1965.

- ^ The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis, Book I (Sects 1–46) Frank Williams, translator, 1987 (E.J. Brill, Leiden) ISBN 90-04-07926-2

- ^ Rudolph, Kurt (1977). "Mandaeism". In Moore, Albert C. (ed.). Iconography of Religions: An Introduction. Vol. 21. Chris Robertson. ISBN 9780800604882.

- ^ a b Rudolph, Kurt (April 1964). "War Der Verfasser Der Oden Salomos Ein "Qumran-Christ"? Ein Beitrag zur Diskussion um die Anfänge der Gnosis". Revue de Qumrân. 4 (16). Peeters: 523–555.

- ^ Aldihisi, Sabah (2008). The story of creation in the Mandaean holy book in the Ginza Rba (PhD). University College London.

- ^ Coughenour, Robert A. (December 1982). "The Wisdom Stance of Enoch's Redactor". Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Period. 13 (1–2). Brill: 52.

- ^ Brikhah S. Nasoraia (2012). "Sacred Text and Esoteric Praxis in Sabian Mandaean Religion" (PDF).

- ^ "The War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ Drower, Ethel Stefana (1953). The Haran Gawaita and the Baptism of Hibil-Ziwa. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

- ^ a b Drower, Ethel Stefana (1937). The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran. Oxford at the Clarendon Press.

- ^ Hachlili, Rachel (1988). Ancient Jewish Art and Archaeology in the Land of Israel. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill. p. 101. ISBN 9004081151.

- ^ Newman, Hillel (2006). Proximity to Power and Jewish Sectarian Groups of the Ancient Period. Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 9789047408352.

- ^ Deutsch, Nathaniel (6 October 2007). "Save the Gnostics". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ Hamidović, David (2010). "About the Links between the Dead Sea Scrolls and Mandaean Liturgy". ARAM Periodical. 22: 441–451. doi:10.2143/ARAM.22.0.2131048.

- ^ a b "St. John the Baptist - Possible relationship with the Essenes | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ a b "The Essenes and the origins of Christianity". The Jerusalem Post | Jpost.com. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- ^ "BBC - History - Ancient History in depth: Lost and Hidden Christianity". BBC. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Denzer, Pam. "Odes of Solomon: Early Hymns of the Jewish Christian Mystical Tradition".

- ^ "The Essenes and the origins of Christianity". The Jerusalem Post | Jpost.com. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Fitzmyer, Joseph A. (2009). The Impact of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-4615-4.

- ^ Stuckenbruck, Loren T.; Gurtner, Daniel M. (26 December 2019). T&T Clark Encyclopedia of Second Temple Judaism Volume One. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-567-65813-5.

- ^ a b Schiffman, Lawrence H.; VanderKam, James C., eds. (2000). "Magharians". Encyclopedia of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-508450-4.

- ^ Harkavy, Abraham. "Le-Ḳorot ha-Kittot be-Yisrael". In Grätz, Heinrich (ed.). Geschichte der Juden (in Hebrew). Vol. iii. p. 496.

Further reading

[edit]- Alexander, David; Alexander, Pat (1983). The Lion handbook to the Bible. Tring: Lion Hudson. ISBN 0-86760-271-6.

- Baldwin, James (1995) [1963]. The fire next time. New York City: Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-60151-1.

- Bauer, Walter; Kraft, Robert A. (1996) [1971]. Orthodoxy and heresy in earliest Christianity. Mifflintown, Pennsylvania: Sigler Press. ISBN 0-9623642-7-4.

- Bennett, Chris; Osburn, Lynn; Osburn, Judy (1995). Green gold the tree of life: marijuana in magic & religion. Frazier Park, California: Access Unlimited. ISBN 0-9629872-2-0.

- Bergmeier, Roland (1993). Die Essener-Berichte des Flavius Josephus: Quellenstudien zu den Essenertexten im Werk des judischen Historiographen. Kampen, Germany: Kok Pharos Publishing House. ISBN 90-390-0014-X.

- Bultmann, Rudolf (1987). "Significance of the Historical Jesus for the Theology of Paul". Faith and understanding. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress. ISBN 0-8006-3202-8.

- Burns, Joshua Ezra (2006). "Essene Sectarianism and Social Differentiation in Judaea After 70 C.E". Harvard Theological Review. 99 (3): 247–74. doi:10.1017/S0017816006001246. S2CID 162491248.

- Durant, Will (1993). Caesar and Christ. MJF Books. ISBN 5-552-12435-9.

- Eisenman, Robert H. (1997). James, the brother of Jesus: the key to unlocking the secrets of early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. New York City: Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-86932-5.

- Ewing, Upton Clary (1994) [1963]. The prophet of the Dead Sea Scrolls: the Essenes and the Early Christians, one and the same holy people: their seven devout practices. Tree of Life Publications. ISBN 0-930852-26-5. OCLC 30358890.

- Ewing, Upton Clary (1961). The Essene Christ. New York City: Philosophical Library. OCLC 384703.

- Legge, Francis (1964). Forerunners and rivals of Christianity, from 330 B.C. to 330 A.D.. New Hyde Park, New York: University Books. LCCN 64024125. OCLC 381558.

- Golb, Norman (1995). Who wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls?: the search for the secret of Qumran. New York City: Scribner. ISBN 0-02-544395-X. OCLC 31009916.

- Lewis, Harvey Spencer (1997) [1929]. Mystical Life of Jesus. San Jose, California: Ancient Mystical Order Rosae Crucis. ISBN 0-912057-46-7. OCLC 43629126.

- Koester, Helmut (1971). "The Theological Aspects of Primitive Christian Heresy". In James McConkey Robinson (ed.). The Future of our religious past: essays in honour of Rudolf Bultmann. New York City: Harper & Row. OCLC 246558.

- Kosmala, Hans (1959). Hebräer-Essener-Christen: Studien zur Vorgeschichte der frühchristlichen Verkündigung. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-02135-8.

- Larson, Martin Alfred (1977). The story of Christian origins: or, The sources and establishment of Western religion. Washington: J.J. Binns. ISBN 0-88331-090-2. OCLC 2810217.

- Larson, Martin Alfred (1967). The Essene heritage: or, The teacher of the scrolls and the gospel Christ. New York City: Philosophical Library. OCLC 712416.

- Lillie, Arthur (1887). Buddhism in Christendom, or, Jesus, the Essene. 1 Paternoster Square, London: Kegan Paul & Co.

- Sanders, E. P. (1992). Judaism: practice and belief, 63 BCE–66 CE. London: SCM Press. ISBN 1-56338-015-3. OCLC 243725142.[page needed]

- Savoy, Gene (1980) [1978]. The Essaei Document: Secrets of an Eternal Race: Codicil to The Decoded New Testament. Reno, Nevada: International Community of Christ. ISBN 0-936202-03-3. OCLC 13952564.

- Schiffman, Lawrence H. (1991). From text to tradition: a history of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism. New York City: Ktav Pub. House. pp. 113–116. ISBN 0-88125-372-3. OCLC 23733614.

- Schonfield, Hugh J. (1984). The Essene Odyssey: The Mystery of the True Teacher and the Essene Impact on the Shaping of Human Destiny. Tisbury: Element Books. ISBN 0-906540-49-6. OCLC 12223220.

- Schonfield, Hugh J. (1991) [1968]. Those Incredible Christians. Tisbury: Element Books. ISBN 0-906540-71-2. OCLC 13536522.

- Shaw, George Bernard (2004) [1912]. Androcles and The Lion. Fairfield, Iowa: 1st World Library – Literary Society. ISBN 1-59540-237-3. OCLC 63203922.

- Smith, Enid S. (October 1959). "The Essenes Who Changed Churchianity". Rays from the Rose Cross.

- Vaclavik, Charles P. (1986). The vegetarianism of Jesus Christ. Three Rivers, California: Kaweah Publishing Company. ISBN 0-945146-00-0. OCLC 26054343.

- Vermes, Geza; Goodman, Martin. The Essenes According to the Classical Sources. JSOT on behalf of the Oxford Centre for Postgraduate Hebrew Studies: Sheffield, 1989.

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Flavius Josephus | |

|---|---|

Imaginary portrait by Thomas Addis Emmet, 1880 | |

| Born | Yosef ben Matityahu[2] c. AD 37[3] |

| Died | c. AD 100[3] (aged 62–63) |

| Children | 5 sons, including:[4] |

| Academic background | |

| Influences | |

| Academic work | |

| Era | Hellenistic Judaism |

| Main interests | |

| Notable works | |

| Influenced | |

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Flavius Josephus (born ad 37/38, Jerusalem—died ad 100, Rome) was a Jewish priest, scholar, and historian who wrote valuable works on the Jewish revolt of 66–70 and on earlier Jewish history. His major books are History of the Jewish War (75–79), The Antiquities of the Jews (93), and Against Apion.

Early life.

Flavius Josephus was born of an aristocratic priestly family in Jerusalem. According to his own account, he was a precocious youth who by the age of 14 was consulted by high priests in matters of Jewish law. At age 16 he undertook a three-year sojourn in the wilderness with the hermit Bannus, a member of one of the ascetic Jewish sects that flourished in Judaea around the time of Christ.

Returning to Jerusalem, he joined the Pharisees—a fact of crucial importance in understanding his later collaboration with the Romans. The Pharisees, despite the unflattering portrayal of them in the New Testament, were for the most part intensely religious Jews and adhered to a strict though nonliteral observance of the Torah. Politically, however, the Pharisees had no sympathy with the intense Jewish nationalism of such sects as the military patriotic Zealots and were willing to submit to Roman rule if only the Jews could maintain their religious independence.

In ad 64 Josephus was sent on an embassy to Rome to secure the release of a number of Jewish priests of his acquaintance who were held prisoners in the capital. There, he was introduced to Poppaea Sabina, Emperor Nero’s second wife, whose generous favour enabled him to complete his mission successfully. During his visit, Josephus was deeply impressed with Rome’s culture and sophistication—and especially its military might.

Military career.

He returned to Jerusalem on the eve of a general revolt against Roman rule. In ad 66 the Jews of Judaea, urged on by the fanatical Zealots, ousted the Roman procurator and set up a revolutionary government in Jerusalem. Along with many others of the priestly class, Josephus counselled compromise but was drawn reluctantly into the rebellion. Despite his moderate stance, he was appointed military commander of Galilee, where (if his own untrustworthy account may be believed) he was obstructed in his efforts at conciliation by the enmity of the local partisans led by John of Giscala. Though realizing the futility of armed resistance, he nevertheless set about fortifying the towns of the north against the forthcoming Roman juggernaut.

The Romans, under the command of the future emperor Vespasian, arrived in Galilee in the spring of ad 67 and quickly broke the Jewish resistance in the north. Josephus managed to hold the fortress of Jotapata for 47 days, but after the fall of the city he took refuge with 40 diehards in a nearby cave. There, to Josephus’ consternation, the beleaguered party voted to perish rather than surrender. Josephus, arguing the immorality of suicide, proposed that each man, in turn, should dispatch his neighbour, the order to be determined by casting lots. Josephus contrived to draw the last lot, and, as one of the two surviving men in the cave, he prevailed upon his intended victim to surrender to the Romans.

Led in chains before Vespasian, Josephus assumed the role of a prophet and foretold that Vespasian would soon be emperor—a prediction that gained in credibility after the death of Nero in ad 68. The stratagem saved his life, and for the next two years he remained a prisoner in the Roman camp. Late in ad 69 Vespasian was proclaimed emperor by his troops: Josephus’ prophecy had come true, and the agreeable Jewish prisoner was given his freedom. From that time on, Josephus attached himself to the Roman cause. He adopted the name Flavius (Vespasian’s family name), accompanied his patron to Alexandria, and there married for the third time. (Josephus’ first wife had been lost at the siege of Jotapata, and his second had deserted him in Judaea.) Josephus later joined the Roman forces under the command of Vespasian’s son and later successor, Titus, at the siege of Jerusalem in ad 70. He attempted to act as mediator between the Romans and the rebels, but, hated by the Jews for his apostasy and distrusted by the Romans as a Jew, he was able to accomplish little. Following the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple, Josephus took up residence in Rome, where he devoted the remainder of his life to literary pursuits under imperial patronage.

Josephus as historian.

Josephus’ first work, Bellum Judaicum (History of the Jewish War), was written in seven books between ad 75 and 79, toward the end of Vespasian’s reign. The original Aramaic has been lost, but the extant Greek version was prepared under Josephus’ personal direction. After briefly sketching Jewish history from the mid-2nd century bc, Josephus presents a detailed account of the great revolt of ad 66–70. He stressed the invincibility of the Roman legions, and apparently one of his purposes in the works was to convince the Diasporan Jews in Mesopotamia, who may have been contemplating revolt, that resistance to Roman arms was pure folly. The work has much narrative brilliance, particularly the description of the siege of Jerusalem; its fluent Greek contrasts sharply with the clumsier idiom of Josephus’ later works and attests the influence of his Greek assistants. In this work, Josephus is extremely hostile to the Jewish patriots and remarkably callous to their fate. The Jewish War not only is the principal source for the Jewish revolt but is especially valuable for its description of Roman military tactics and strategy.

In Rome, Josephus had been granted citizenship and a pension. He was a favourite at the courts of the emperors Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian, and he enjoyed the income from a tax-free estate in Judaea. He had divorced his third wife, married an aristocratic heiress from Crete, and given Roman names to his children. He had written an official history of the revolt and was loathed by the Jews as a turncoat and traitor. Yet despite all of this, Josephus had by no means abandoned his Judaism. His greatest work, Antiquitates Judaicae (The Antiquities of the Jews), completed in 20 books in ad 93, traces the history of the Jews from creation to just before the outbreak of the revolt of ad 66–70. It was an attempt to present Judaism to the Hellenistic world in a favourable light. By virtually ignoring the Prophets, by embellishing biblical narratives, and by stressing the rationality of Judaic laws and institutions, he stripped Judaism of its fanaticism and made it appealing to the cultivated and reasonable man. Historically, the coverage is patchy and shows the fatigue of the author, then in his middle 50s. But throughout, sources are preserved that otherwise would have been lost, and, for Jewish history during the period of the Second Commonwealth, the work is invaluable.

The Antiquities contains two famous references to Jesus Christ: the one in Book XX calls him the “so-called Christ.” The implication in the passage in Book XVIII of Christ’s divinity could not have come from Josephus and undoubtedly represents the tampering (if not invention) of a later Christian copyist.

Appended to the Antiquities was a Vita (Life), which is less an autobiography than an apology for Josephus’ conduct in Galilee during the revolt. It was written to defend himself against the charges of his enemy Justus of Tiberias, who claimed that Josephus was responsible for the revolt. In his defense, he contradicted the account given in his more trustworthy Jewish War, presenting himself as a consistent partisan of Rome and thus a traitor to the rebellion from the start. Josephus appears in a much better light in a work generally known as Contra Apionem (Against Apion, though the earlier titles Concerning the Antiquity of the Jews and Against the Greeks are more apposite). Of its two books, the first answers various anti-Semitic charges leveled at the Jews by Hellenistic writers, while the second provides an argument for the ethical superiority of Judaism over Hellenism and shows Josephus’ commitment to his religion and his culture.

Since Against Apion mentions the death of Agrippa II, it is probable that Josephus lived into the 2nd century; but Agrippa’s death date is uncertain, and it is possible that Josephus died earlier, in the reign of Domitian, sometime after ad 93.

Legacy

As a historian, Josephus shares the faults of most ancient writers: his analyses are superficial, his chronology faulty, his facts exaggerated, his speeches contrived. He is especially tendentious when his own reputation is at stake. His Greek style, when it is truly his, does not earn for him the epithet “the Greek Livy” that often is attached to his name. Yet he unites in his person the traditions of Judaism and Hellenism, provides a connecting link between the secular world of Rome and the religious heritage of the Bible, and offers many insights into the mentality of subject peoples under the Roman Empire.

Personally, Josephus was vain, callous, and self-seeking. There was not a shred of heroism in his character, and for his toadyism he well deserved the scorn heaped upon him by his countrymen. But it may be said in his defense that he remained true to his Pharisee beliefs and, being no martyr, did what he could for his people.

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Flavius Josephus[a] (/dʒoʊˈsiːfəs/;[9] Ancient Greek: Ἰώσηπος, Iṓsēpos; c. AD 37 – c. 100) or Yosef ben Mattityahu (Hebrew: יוֹסֵף בֵּן מַתִּתְיָהוּ) was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing The Jewish War, he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of priestly descent and a mother who claimed royal ancestry.

He initially fought against the Roman Empire during the First Jewish–Roman War as general of the Jewish forces in Galilee, until surrendering in AD 67 to the Roman army led by military commander Vespasian after the six-week siege of Yodfat. Josephus claimed the Jewish messianic prophecies that initiated the First Jewish–Roman War made reference to Vespasian becoming Roman emperor. In response, Vespasian decided to keep him as a slave and presumably interpreter. After Vespasian became emperor in AD 69, he granted Josephus his freedom, at which time Josephus assumed the Emperor's family name of Flavius.[10]

Flavius Josephus fully defected to the Roman side and was granted Roman citizenship. He became an advisor and close associate of Vespasian's son Titus, serving as his translator during Titus's protracted siege of Jerusalem in AD 70, which resulted in the near-total razing of the city and the destruction of the Second Temple.

Josephus recorded the Great Jewish Revolt (AD 66–70), including the siege of Masada. His most important works were The Jewish War (c. 75) and Antiquities of the Jews (c. 94).[11] The Jewish War recounts the Jewish revolt against Roman occupation. Antiquities of the Jews recounts the history of the world from a Jewish perspective for an ostensibly Greek and Roman audience. These works provide insight into first-century Judaism and the background of Early Christianity.[11] Josephus's works are the chief source next to the Bible for the history and antiquity of ancient Israel, and provide an independent extra-biblical account of such figures as Pontius Pilate, Herod the Great, John the Baptist, James, brother of Jesus, and Jesus of Nazareth.[12]

Biography

[edit]

Josephus was born into one of Jerusalem's elite families.[13] He was the second-born son of Matthias, a Jewish priest. His older full-blooded brother was also, like his father, called Matthias.[14] Their mother was an aristocratic woman who was descended from the royal and formerly ruling Hasmonean dynasty.[15] Josephus's paternal grandparents were a man also named Joseph(us) and his wife—an unnamed Hebrew noblewoman—distant relatives of each other.[16] Josephus's family was wealthy. He descended through his father from the priestly order of the Jehoiarib, which was the first of the 24 orders of priests in the Temple in Jerusalem.[17] Josephus calls himself a fourth-generation descendant of "High Priest Jonathan", referring to either Jonathan Apphus or Alexander Jannaeus.[17] He was raised in Jerusalem and educated alongside his brother.[18]

In his mid twenties, he traveled to negotiate with Emperor Nero for the release of some Jewish priests.[19] Upon his return to Jerusalem, at the outbreak of the First Jewish–Roman War, Josephus was appointed the military governor of Galilee.[20] His arrival in Galilee, however, was fraught with internal division: the inhabitants of Sepphoris and Tiberias opted to maintain peace with the Romans; the people of Sepphoris enlisted the help of the Roman army to protect their city,[21] while the people of Tiberias appealed to King Agrippa's forces to protect them from the insurgents.[22] Josephus trained 65,000 troops in the region.[12]

Josephus also contended with John of Gischala who had also set his sight over the control of Galilee. Like Josephus, John had amassed to himself a large band of supporters from Gischala (Gush Halab) and Gabara,[b] including the support of the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem.[26] Meanwhile, Josephus fortified several towns and villages in Lower Galilee, among which were Tiberias, Bersabe, Selamin, Japha, and Tarichaea, in anticipation of a Roman onslaught.[27] In Upper Galilee, he fortified the towns of Jamnith, Seph, Mero, and Achabare, among other places.[27] Josephus, with the Galileans under his command, managed to bring both Sepphoris and Tiberias into subjection,[21] but was eventually forced to relinquish his hold on Sepphoris by the arrival of Roman forces under Placidus the tribune and later by Vespasian himself. Josephus first engaged the Roman army at a village called Garis, where he launched an attack against Sepphoris a second time, before being repulsed.[28] At length, he resisted the Roman army in its siege of Yodfat (Jotapata) until it fell to the Roman army in the lunar month of Tammuz, in the thirteenth year of Nero's reign.

After the Jewish garrison of Yodfat fell under siege, the Romans invaded, killing thousands; the survivors committed suicide. According to Josephus, he was trapped in a cave with 40 of his companions in July 67 AD. The Romans (commanded by Flavius Vespasian and his son Titus, both subsequently Roman emperors) asked the group to surrender, but they refused. According to Josephus's account, he suggested a method of collective suicide;[29] they drew lots and killed each other, one by one, and Josephus happened to be one of two men that were left who surrendered to the Roman forces and became prisoners.[c] In 69 AD, Josephus was released.[31] According to his account, he acted as a negotiator with the defenders during the siege of Jerusalem in 70 AD, during which time his parents were held as hostages by Simon bar Giora.[32]

While being confined at Yodfat (Jotapata), Josephus claimed to have experienced a divine revelation that later led to his speech predicting Vespasian would become emperor. After the prediction came true, he was released by Vespasian, who considered his gift of prophecy to be divine. Josephus wrote that his revelation had taught him three things: that God, the creator of the Jewish people, had decided to "punish" them; that "fortune" had been given to the Romans; and that God had chosen him "to announce the things that are to come".[33][34][35] To many Jews, such claims were simply self-serving.[36]

In 71 AD, he went to Rome as part of the entourage of Titus. There, he became a Roman citizen and client of the ruling Flavian dynasty. In addition to Roman citizenship, he was granted accommodation in the conquered Judaea and a pension. While in Rome and under Flavian patronage, Josephus wrote all of his known works. Although he only ever calls himself "Josephus" in his writings, later historians refer to him as "Flavius Josephus", confirming that he adopted the nomen Flavius from his patrons, as was the custom amongst freedmen.[5][6]

Vespasian arranged for Josephus to marry a captured Jewish woman, whom he later divorced. Around the year 71, Josephus married an Alexandrian Jewish woman as his third wife. They had three sons, of whom only Flavius Hyrcanus survived childhood. Josephus later divorced his third wife. Around 75, he married his fourth wife, a Greek Jewish woman from Crete, who was a member of a distinguished family. They had two sons, Flavius Justus and Flavius Simonides Agrippa.

Josephus's life story remains ambiguous. He was described by Harris in 1985 as a law-observant Jew who believed in the compatibility of Judaism and Graeco-Roman thought, commonly referred to as Hellenistic Judaism.[11] Josippon, the Hebrew version of Josephus, contains changes.[37] His critics were never satisfied as to why he failed to commit suicide in Galilee, and after his capture, accepted the patronage of Romans.

Scholarship and impact on history

[edit]The works of Josephus provide information about the First Jewish–Roman War and also represent literary source material for understanding the context of the Dead Sea Scrolls and late Temple Judaism.

Josephan scholarship in the 19th and early 20th centuries took an interest in Josephus's relationship to the sect of the Pharisees.[citation needed] Some[who?] portrayed him as a member of the sect and as a traitor to the Jewish nation—a view which became known as the classical concept of Josephus.[38] In the mid-20th century, a new generation of scholars[who?] challenged this view and formulated the modern concept of Josephus. They consider him a Pharisee but describe him in part as patriot and a historian of some standing. In his 1991 book, Steve Mason argued that Josephus was not a Pharisee but an orthodox Aristocrat-Priest who became associated with the philosophical school of the Pharisees as a matter of deference, and not by willing association.[39]

Impact on history and archaeology

[edit]The works of Josephus include useful material for historians about individuals, groups, customs, and geographical places. However, modern historians have been cautious of taking his writings at face value. For example, Carl Ritter, in his highly influential Erdkunde in the 1840s, wrote in a review of authorities on the ancient geography of the region:

Josephus mentions that in his day there were 240 towns and villages scattered across Upper and Lower Galilee,[41] some of which he names. Josephus's works are the primary source for the chain of Jewish high priests during the Second Temple period. A few of the Jewish customs named by him include the practice of hanging a linen curtain at the entrance to one's house,[42] and the Jewish custom to partake of a Sabbath-day's meal around the sixth-hour of the day (at noon).[43] He notes also that it was permissible for Jewish men to marry many wives (polygamy).[44] His writings provide a significant, extra-Biblical account of the post-Exilic period of the Maccabees, the Hasmonean dynasty, and the rise of Herod the Great. He also describes the Sadducees, the Pharisees and Essenes, the Herodian Temple, Quirinius's census and the Zealots, and such figures as Pontius Pilate, Herod the Great, Agrippa I and Agrippa II, John the Baptist, James the brother of Jesus, and Jesus.[45] Josephus represents an important source for studies of immediate post-Temple Judaism and the context of early Christianity.

A careful reading of Josephus's writings and years of excavation allowed Ehud Netzer, an archaeologist from Hebrew University, to discover what he considered to be the location of Herod's Tomb, after searching for 35 years.[46] It was above aqueducts and pools, at a flattened desert site, halfway up the hill to the Herodium, 12 km south of Jerusalem—as described in Josephus's writings.[47] In October 2013, archaeologists Joseph Patrich and Benjamin Arubas challenged the identification of the tomb as that of Herod.[48] According to Patrich and Arubas, the tomb is too modest to be Herod's and has several unlikely features.[48] Roi Porat, who replaced Netzer as excavation leader after the latter's death, stood by the identification.[48]

Josephus's writings provide the first-known source for many stories considered as Biblical history, despite not being found in the Bible or related material. These include Ishmael as the founder of the Arabs,[49] the connection of "Semites", "Hamites" and "Japhetites" to the classical nations of the world, and the story of the siege of Masada.[50]

Josephus's original audience

[edit]Scholars debate about Josephus's intended audience. For example, Antiquities of the Jews could be written for Jews—"a few scholars from Laqueur onward have suggested that Josephus must have written primarily for fellow Jews (if also secondarily for Gentiles). The most common motive suggested is repentance: in later life he felt so bad about the traitorous War that he needed to demonstrate … his loyalty to Jewish history, law and culture."[51] However, Josephus's "countless incidental remarks explaining basic Judean language, customs and laws … assume a Gentile audience. He does not expect his first hearers to know anything about the laws or Judean origins."[52] The issue of who would read this multi-volume work is unresolved. Other possible motives for writing Antiquities could be to dispel the misrepresentation of Jewish origins[53] or as an apologetic to Greek cities of the Diaspora in order to protect Jews and to Roman authorities to garner their support for the Jews facing persecution.[54]

Literary influence and translations

[edit]Josephus was a very popular writer with Christians in the 4th century and beyond as an independent source to the events before, during, and after the life of Jesus of Nazareth. Josephus was always accessible in the Greek-reading Eastern Mediterranean. His works were translated into Latin, but often in abbreviated form such as Pseudo-Hegesippus's 4th century Latin version of The Jewish War (Bellum Judaicum). Christian interest in The Jewish War was largely out of interest in the downfall of the Jews and the Second Temple, which was widely considered divine punishment for the crime of killing Jesus. Improvements in printing technology (the Gutenberg Press) led to his works receiving a number of new translations into the vernacular languages of Europe, generally based on the Latin versions. Only in 1544 did a version of the standard Greek text become available in French, edited by the Dutch humanist Arnoldus Arlenius. The first English translation, by Thomas Lodge, appeared in 1602, with subsequent editions appearing throughout the 17th century. The 1544 Greek edition formed the basis of the 1732 English translation by William Whiston, which achieved enormous popularity in the English-speaking world. It was often the book—after the Bible—that Christians most frequently owned. Whiston claimed that certain works by Josephus had a similar style to the Epistles of St. Paul.[55][56] Later editions of the Greek text include that of Benedikt Niese, who made a detailed examination of all the available manuscripts, mainly from France and Spain. Henry St. John Thackeray and successors such as Ralph Marcus used Niese's version for the Loeb Classical Library edition widely used today.

On the Jewish side, Josephus was far more obscure, as he was perceived as a traitor. Rabbinical writings for a millennium after his death (e.g. the Mishnah) almost never call out Josephus by name, although they sometimes tell parallel tales of the same events that Josephus narrated. An Italian Jew writing in the 10th century indirectly brought Josephus back to prominence among Jews: he authored the Yosippon, which paraphrases Pseudo-Hegesippus's Latin version of The Jewish War, a Latin version of Antiquities, as well as other works. The epitomist also adds in his own snippets of history at times. Jews generally distrusted Christian translations of Josephus until the Haskalah ("Jewish Enlightenment") in the 19th century, when sufficiently "neutral" vernacular language translations were made. Kalman Schulman finally created a Hebrew translation of the Greek text of Josephus in 1863, although many rabbis continued to prefer the Yosippon version. By the 20th century, Jewish attitudes toward Josephus had softened, as he gave the Jews a respectable place in classical history. Various parts of his work were reinterpreted as more inspiring and favorable to the Jews than the Renaissance translations by Christians had been. Notably, the last stand at Masada (described in The Jewish War), which past generations had deemed insane and fanatical, received a more positive reinterpretation as an inspiring call to action in this period.[56][57]

The standard editio maior of the various Greek manuscripts is that of Benedictus Niese, published 1885–95. The text of Antiquities is damaged in some places. In the Life, Niese follows mainly manuscript P, but refers also to AMW and R. Henry St. John Thackeray for the Loeb Classical Library has a Greek text also mainly dependent on P. André Pelletier edited a new Greek text for his translation of Life. The ongoing Münsteraner Josephus-Ausgabe of Münster University will provide a new critical apparatus. Late Old Slavonic translations of the Greek also exist, but these contain a large number of Christian interpolations.[58]

Evaluation as a military commander

[edit]Author Joseph Raymond calls Josephus "the Jewish Benedict Arnold" for betraying his own troops at Jotapata,[59] while historian Mary Smallwood, in the introduction to the translation of The Jewish War by G. A. Williamson, writes:

Historiography and Josephus

[edit]

In the Preface to Jewish Wars, Josephus criticizes historians who misrepresent the events of the Jewish–Roman War, writing that "they have a mind to demonstrate the greatness of the Romans, while they still diminish and lessen the actions of the Jews."[61] Josephus states that his intention is to correct this method but that he "will not go to the other extreme ... [and] will prosecute the actions of both parties with accuracy."[62] Josephus confesses he will be unable to contain his sadness in transcribing these events; to illustrate this will have little effect on his historiography, Josephus suggests, "But if any one be inflexible in his censures of me, let him attribute the facts themselves to the historical part, and the lamentations to the writer himself only."[62]

His preface to Antiquities offers his opinion early on, saying, "Upon the whole, a man that will peruse this history, may principally learn from it, that all events succeed well, even to an incredible degree, and the reward of felicity is proposed by God."[63] After inserting this attitude, Josephus contradicts Berossus: "I shall accurately describe what is contained in our records, in the order of time that belongs to them ... without adding any thing to what is therein contained, or taking away any thing therefrom."[63] He notes the difference between history and philosophy by saying, "[T]hose that read my book may wonder how it comes to pass, that my discourse, which promises an account of laws and historical facts, contains so much of philosophy."[64]

In both works, Josephus emphasizes that accuracy is crucial to historiography. Louis H. Feldman notes that in Wars, Josephus commits himself to critical historiography, but in Antiquities, Josephus shifts to rhetorical historiography, which was the norm of his time.[65] Feldman notes further that it is significant that Josephus called his later work "Antiquities" (literally, archaeology) rather than history; in the Hellenistic period, archaeology meant either "history from the origins or archaic history."[66] Thus, his title implies a Jewish peoples' history from their origins until the time he wrote. This distinction is significant to Feldman, because "in ancient times, historians were expected to write in chronological order," while "antiquarians wrote in a systematic order, proceeding topically and logically" and included all relevant material for their subject.[66] Antiquarians moved beyond political history to include institutions and religious and private life.[67] Josephus does offer this wider perspective in Antiquities.

Works

[edit]

The works of Josephus are major sources of our understanding of Jewish life and history during the first century.[68]

- (c. 75) War of the Jews, The Jewish War, Jewish Wars, or History of the Jewish War (commonly abbreviated JW, BJ or War)

- (c. 94) Antiquities of the Jews, Jewish Antiquities, or Antiquities of the Jews/Jewish Archeology (frequently abbreviated AJ, AotJ or Ant. or Antiq.)

- (c. 97) Flavius Josephus Against Apion, Against Apion, Contra Apionem, or Against the Greeks, on the antiquity of the Jewish people (usually abbreviated CA)

- (c. 99) Life of Josephus, or Autobiography of Josephus (abbreviated Life or Vita)

The Jewish War

[edit]His first work in Rome was an account of the Jewish War, addressed to certain "upper barbarians"—usually thought to be the Jewish community in Mesopotamia—in his "paternal tongue" (War I.3), arguably the Western Aramaic language. In AD 78 he finished a seven-volume account in Greek known as the Jewish War (Latin Bellum Judaicum or De Bello Judaico). It starts with the period of the Maccabees and concludes with accounts of the fall of Jerusalem, and the subsequent fall of the fortresses of Herodion, Macharont and Masada and the Roman victory celebrations in Rome, the mopping-up operations, Roman military operations elsewhere in the empire and the uprising in Cyrene. Together with the account in his Life of some of the same events, it also provides the reader with an overview of Josephus's own part in the events since his return to Jerusalem from a brief visit to Rome in the early 60s (Life 13–17).[69]

In the wake of the suppression of the Jewish revolt, Josephus would have witnessed the marches of Titus's triumphant legions leading their Jewish captives, and carrying treasures from the despoiled Temple in Jerusalem. It was against this background that Josephus wrote his War. He blames the Jewish War on what he calls "unrepresentative and over-zealous fanatics" among the Jews, who led the masses away from their traditional aristocratic leaders (like himself), with disastrous results. For example, Josephus writes that "Simon [bar Giora] was a greater terror to the people than the Romans themselves."[70] Josephus also blames some of the Roman governors of Judea, representing them as corrupt and incompetent administrators.

Jewish Antiquities

[edit]The next work by Josephus is his 21-volume Antiquities of the Jews, completed during the last year of the reign of the Emperor Flavius Domitian, around 93 or 94 AD. In expounding Jewish history, law and custom, he is entering into many philosophical debates current in Rome at that time. Again he offers an apologia for the antiquity and universal significance of the Jewish people. Josephus claims to be writing this history because he "saw that others perverted the truth of those actions in their writings",[71] those writings being the history of the Jews. In terms of some of his sources for the project, Josephus says that he drew from and "interpreted out of the Hebrew Scriptures"[72] and that he was an eyewitness to the wars between the Jews and the Romans,[71] which were earlier recounted in Jewish Wars.

He outlines Jewish history beginning with the creation, as passed down through Jewish historical tradition. Abraham taught science to the Egyptians, who, in turn, taught the Greeks.[73] Moses set up a senatorial priestly aristocracy, which, like that of Rome, resisted monarchy. The great figures of the Tanakh are presented as ideal philosopher-leaders. He includes an autobiographical appendix defending his conduct at the end of the war when he cooperated with the Roman forces.

Louis H. Feldman outlines the difference between calling this work Antiquities of the Jews instead of History of the Jews. Although Josephus says that he describes the events contained in Antiquities "in the order of time that belongs to them,"[63] Feldman argues that Josephus "aimed to organize [his] material systematically rather than chronologically" and had a scope that "ranged far beyond mere political history to political institutions, religious and private life."[67]

Life of Flavius Josephus

[edit]An autobiographical text written by Josephus in approximately 94–99 CE – possibly as an appendix to his Antiquities of the Jews (cf. Life 430) – where the author for the most part re-visits the events of the War and his tenure in Galilee as governor and commander, apparently in response to allegations made against him by Justus of Tiberias (cf. Life 336).

Against Apion

[edit]Josephus's Against Apion is a two-volume defence of Judaism as classical religion and philosophy, stressing its antiquity, as opposed to what Josephus claimed was the relatively more recent tradition of the Greeks. Some anti-Judaic allegations ascribed by Josephus to the Greek writer Apion and myths accredited to Manetho are also addressed.

Spurious works

[edit]- (date unknown) Josephus's Discourse to the Greeks concerning Hades (spurious; adaptation of "Against Plato, on the Cause of the Universe" by Hippolytus of Rome)

See also

[edit]- Josephus on Jesus

- Josephus problem – a mathematical problem named after Josephus

- Josippon

- Pseudo-Philo

Notes and references

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Some modern authors give his birth name, including patronymic, which was "Yosef ben Mattityahu", “Yoseph bar Mattityahu" or "Yosef ben Matityahu",[5][6][7][8] literally meaning "Joseph son of Matthias". That is what he calls himself at the start of The Jewish War (Ἰώσηπος Ματθίου παῖς, Iósipos Matthíou país). "Flavius" was not part of his birth name, and was only adopted later.[5]

- ^ A large village in Galilee during the 1st century AD, located to the north of Nazareth. In antiquity, the town was called "Garaba", but in Josephus's historical works of antiquity, the town is mentioned by its Greek corruption, "Gabara".[23][24][25]

- ^ This method as a mathematical problem is referred to as the Josephus problem, or Roman roulette.[30]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Josephus 1737, 18.8.1.

- ^ "Flavius Josephus".

- ^ a b Mason 2000.

- ^ Schürer 1973, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Hollander, William den (2014). Josephus, the Emperors, and the City of Rome: From Hostage to Historian. BRILL. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-90-04-26683-4.

- ^ a b Collins, John J.; Harlow, Daniel C. (2012). "Josephus". Early Judaism: A Comprehensive Overview. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4674-3739-4.

- ^ Ben-Ari, Nitsa (2003). "The double conversion of Ben-Hur: a case of manipulative translation" (PDF). Target. 14 (2): 263–301. doi:10.1075/target.14.2.05ben. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

The converts themselves were banned from society as outcasts and so was their historiographic work or, in the more popular historical novels, their literary counterparts. Josephus Flavius, formerly Yosef Ben Matityahu (34–95), had been shunned, then banned as a traitor.

- ^ Goodman 2019, p. 186.

- ^ "Josephus". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins Publishers.

- ^ Mimouni 2012, p. 133.

- ^ a b c Harris 1985.

- ^ a b Josephus, Flavius; Whiston, William; Maier, Paul L. (1999). The New Complete Works of Josephus. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications. p. 7-8. ISBN 9780825429484.

- ^ Goodman 2007, p. 8: "Josephus was born into the ruling elite of Jerusalem"

- ^ Mason 2000, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Nodet 1997, p. 250.

- ^ "Josephus Lineage" (PDF). History of the Daughters (Fourth ed.). Sonoma, California: L P Publishing. December 2012. pp. 349–350.

- ^ a b Schürer 1973, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Mason 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Josephus, Vita § 3

- ^ Goldberg, G. J. "The Life of Flavius Josephus". Josephus.org. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ a b Josephus, Vita, § 67

- ^ Josephus, Vita, § 68

- ^ Klausner, J. (1934). "Qobetz". Journal of the Jewish Palestinian Exploration Society (in Hebrew). 3: 261–263.

- ^ Rappaport 2006, p. 44 [note 2].

- ^ Safrai 1985, pp. 59–62.

- ^ Josephus, Vita, § 25; § 38; Josephus, Flavius (1926). The Life of Josephus. doi:10.4159/DLCL.josephus-life.1926. Retrieved 31 May 2016. – via digital Loeb Classical Library (subscription required)

- ^ a b Josephus, Vita, § 37

- ^ Josephus, Vita, § 71

- ^ Josephus, The Jewish War. Book 3, Chapter 8, par. 7

- ^ Cf. this example, Roman Roulette. Archived February 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jewish War IV.622–629

- ^ Josephus, The Jewish War (5.13.1. and 5.13.3.)

- ^ Gray 1993, pp. 35–38.

- ^ Aune 1991, p. 140.

- ^ Gnuse 1996, pp. 136–142.

- ^ Goodman 2007, p. 9: "Later generations of Jews have been inclined to treat such claims as self-serving"

- ^ Neuman, Abraham A. (1952). "Josippon and the Apocrypha". The Jewish Quarterly Review. 43 (1): 1–26. doi:10.2307/1452910. ISSN 0021-6682. JSTOR 1452910.

- ^ Millard 1997, p. 306.

- ^ Mason, Steve (April 2003). "Flavius Josephus and the Pharisees". The Bible and Interpretation. Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- ^ Ritter, C. (1866). The Comparative Geographie of Palestine and the Sinaitic Peninsula. T. & T. Clark.

- ^ Josephus, Vita § 45

- ^ Josephus 1737, 3.6.4: After describing the curtain that hung in the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, Josephus adds: "Whence that custom of ours is derived, of having a fine linen veil, after the temple has been built, to be drawn over the entrances."

- ^ Josephus, Vita § 54

- ^ Flavius Josephus, The Works of Flavius Josephus. Translated by William Whiston, A. M. Auburn and Buffalo. John E. Beardsley: 1895, s.v. The Jewish War 1.24.2 (end) (1.473).

- ^ Whealey, Alice (2003). Josephus on Jesus: The Testimonium Flavianum Controversy from Late Antiquity to Modern Times. Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8204-5241-8.

In the sixteenth century the authenticity of the text [Testimonium Flavianum] was publicly challenged, launching a controversy that has still not been resolved today

- ^ Kraft, Dina (9 May 2007). "Archaeologist Says Remnants of King Herod's Tomb Are Found". NY Times. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Murphy 2008, p. 99.

- ^ a b c Hasson, Nir (11 October 2013). "Archaeological stunner: Not Herod's Tomb after all?". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.