The decisive dates for the Early Christian Movement are generally deemed to be from the beginning of the Maccabean Revolt (167 BCC to 160 BCC) to the final destruction of Jewish national independence in 70 CC, and later in the Bar-Kokba revolt from 132 CC to 135 CC -- a period of about three centuries. During this fruitful epoch, Jewish patriotism asserted itself through the Maccabean movement, and, for a time, won national independence.

The effects of this development on Judaism as a whole were significant. The range of Jewish influence in Palestine was decisively extended. The community expanded on a large scale, and Judaism itself became intensely proud and self-conscious. These results were by no means destroyed when Judea, her national independence finally lost, became a Roman province in 6 CC. The national feeling flared up from time to time and culminated finally in the disastrous rebellion against Rome from 66 CC to 70 CC, which ended in the destruction of the Temple and the ruin of the Holy City.

The party of peace, which had never approved of the rebellion, now for a time triumphed, and under Jochanan ben Zakkai, Judaism was reorganized at Jamnia. But the nationalist elements were by no means finally overcome, and rebellions broke out again, first in 117 CC, and finally in the great revolt of 132 CC to 135 CC, under Bar-Kokba, in which the most famous rabbi of the time, Akiba, took a prominent part, and with other rabbis, suffered martyrdom.

After the suppression of the final rebellion, Judaism devoted its energies, without distraction, to the task of consolidating its life as a community primarily on a religious basis. The teachers of the Law werre now supreme as leaders, and the Jews became "The People of the Book."

88888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

The Maccabean Revolt (Hebrew: מרד החשמונאים) was a Jewish rebellion led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and against Hellenistic influence on Jewish life. The main phase of the revolt lasted from 167 to 160 BCE and ended with the Seleucids in control of Judea, but conflict between the Maccabees, Hellenized Jews, and the Seleucids continued until 134 BCE, with the Maccabees eventually attaining independence.

Seleucid King Antiochus IV Epiphanes launched a massive campaign of repression against the Jewish religion in 168 BCE. The reason he did so is not entirely clear, but it seems to have been related to the King mistaking an internal conflict among the Jewish priesthood as a full-scale rebellion. Jewish practices were banned, Jerusalem was placed under direct Seleucid control, and the Second Temple in Jerusalem was made the site of a syncretic Pagan-Jewish cult. This repression triggered exactly the revolt that Antiochus IV had feared, with a group of Jewish fighters led by Judas Maccabeus (Judah Maccabee) and his family rebelling in 167 BCE and seeking independence. The rebels as a whole would come to be known as the Maccabees, and their actions would be chronicled later in the books of 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees.

The rebellion started as a guerrilla movement in the Judean countryside, raiding towns and terrorizing Greek officials far from direct Seleucid control, but it eventually developed a proper army capable of attacking the fortified Seleucid cities. In 164 BCE, the Maccabees captured Jerusalem, a significant early victory. The subsequent cleansing of the temple and rededication of the altar on 25 Kislev is the source of the festival of Hanukkah. The Seleucids eventually relented and unbanned Judaism, but the more radical Maccabees, not content with merely reestablishing Jewish practices under Seleucid rule, continued to fight, pushing for a more direct break with the Seleucids. Judas Maccabeus died in 160 BCE at the Battle of Elasa against the Greek general Bacchides, and the Seleucids reestablished direct control for a time, but remnants of the Maccabees under Judas's brother Jonathan Apphus continued to resist from the countryside. Eventually, internal division among the Seleucids and problems elsewhere in their empire would give the Maccabees their chance for proper independence. In 141 BCE, Simon Thassi succeeded in expelling the Greeks from their citadel in Jerusalem. An alliance with the Roman Republic helped guarantee their independence. Simon would go on to establish an independent Hasmonean kingdom.

The revolt had a great impact on Jewish nationalism, as an example of a successful campaign to establish political independence and resist governmental anti-Jewish suppression.

Background

[edit]

Beginning in 338 BCE, Alexander the Great began an invasion of the Persian Empire. In 333–332 BCE, Alexander's Macedonian forces conquered the Levant and Palestine. At the time, Judea was home to many Jews who had returned from exile in Babylon thanks to the Persians. Alexander's empire was partitioned in 323 BCE after Alexander's death, and after the Wars of the Diadochi, the territory was taken by what would become Ptolemaic Egypt in 302–301 BCE.[1] Another of the Greek successor states, the Seleucid Empire, would conquer Judea from Egypt during a series of campaigns from 235–198 BCE. During both Ptolemaic and Seleucid rule, many Jews learned Koine Greek, especially upper class Jews and Jewish minorities in towns further afield from Jerusalem and more attached to Greek trading networks.[2] Greek philosophical ideas spread through the region as well. A Greek translation of the scriptures, the Septuagint, was also created during the third century BCE.[3] Many Jews adopted dual names with both a Greek name and a Hebrew name, such as Jason and Joshua.[4][5] Still, many Jews continued to speak the Aramaic language, the language that descended from what was spoken during the Babylonian exile.[6]

In general, the ruling Greek policy during this time period was to let Jews manage their own affairs and not interfere overtly with religious matters. Greek authors in the third century BCE who wrote about Judaism did so mostly positively.[7][8] Cultural change did happen, but was largely driven by Jews themselves inspired by ideas from abroad; Greek rulers did not undertake explicit programs of forced Hellenization. Antiochus IV Epiphanes came to the throne of the Seleucids in 175 BCE, and did not change this policy. He appears to have done little to antagonize the region at first, and the Jews were largely content under his rule. One element that would come to later prominence was Antiochus IV replacing the high priest Onias III with his brother Jason after Jason offered a large sum of money to Antiochus.[9] Jason also sought and received permission to make Jerusalem a self-governing polis, albeit with Jason able to control the citizenship lists of who would be able to vote and hold political office. These changes did not immediately appear to rouse any particular complaint from the majority of the citizenry in Jerusalem, and presumably he still kept the basic Jewish laws and tenets.[9][10] Three years later, a newcomer named Menelaus offered an even larger bribe to Antiochus IV for the position of high priest. Jason, resentful, turned against Antiochus IV; additionally, a rumor spread that Menelaus had sold golden temple artifacts to help pay for the bribe, leading to unhappiness, especially among the city council Jason had established. This conflict was largely political rather than cultural; all sides, at this point, were "Hellenized", content with Seleucid rule, and primarily divided over Menelaus's alleged corruption and sacrilege.[2][6]

In 170–168 BCE, the Sixth Syrian War between the Seleucids and the Ptolemaic Egyptians arose. Antiochus IV led an army to attack Egypt. On his way back through Jerusalem after the successful campaign, High Priest Menelaus allegedly invited Antiochus inside the Second Temple (in violation of Jewish law), and he raided the temple treasury for 1800 talents.[note 1] Tensions with the Ptolemaic dynasty continued, and Antiochus rode out on campaign again in 168 BCE.[12] Jason heard a rumor that Antiochus had perished, and launched an attempted coup against Menelaus in Jerusalem. Hearing of this, Antiochus, who was not dead, apparently interpreted this factional infighting as a revolt against his personal authority, and sent an army to crush Jason's plotters. From 168–167 BCE, the conflict spiraled out of control, and government policy radically shifted. Thousands in Jerusalem were killed and thousands more were enslaved; the city was attacked twice; new Greek governors were sent; the government seized land and property from Jason's supporters; and the Temple in Jerusalem was made the site of a syncretic Greek-Jewish religious group, polluting it in the eyes of the devout Jews.[13] A new citadel garrisoned by Greeks and pro-Seleucid Jews, the Acra, was built in Jerusalem. Antiochus IV issued decrees officially suppressing the Jewish religion; subjects were required to eat pork and violate Jewish dietary law, work on the Jewish Sabbath, cease circumcising their sons, and so on.[note 2] The policy of tolerance of Jewish worship was at an end.[2][14]

The rebellion

[edit]Mattathias sparks the uprising (167 BCE)

[edit]

In the aftermath of Antiochus IV issuing his decrees forbidding Jewish religious practice, a campaign of land confiscations paired with shrine and altar-building took place in the Judean countryside.[16] A rural Jewish priest from Modein, Mattathias (Hebrew: Matityahu) of the Hasmonean family, sparked the revolt against the Seleucid Empire by refusing to worship the Greek gods at Modein's new altar. Mattathias killed a Jew who had stepped forward to take Mattathias' place in sacrificing to an idol as well as the Greek officer who was sent to enforce the sacrifice. He then destroyed the altar.[17] Afterwards, he and his five sons fled to the nearby mountains, which sat directly next to Modein.[18]

Guerrilla campaign (167–164 BCE)

[edit]After Mattathias' death about one year later in 166 BCE, his son Judas Maccabeus (Hebrew: Judah Maccabee) led a band of Jewish dissidents that would eventually absorb other groups opposed to Seleucid rule and grow into an army. While unable to directly strike Seleucid power at first, Judas's forces could maraud the countryside and attack Hellenized Jews, of whom there were many. The Maccabees destroyed Greek altars in the villages, forcibly circumcised boys, burnt villages, and drove Hellenized Jews off their land.[19][17] Judas's nickname "Maccabee", now used to describe the Jewish partisans as a whole, is probably taken from the word "hammer" (Aramaic: maqqaba; Hebrew: makebet); the term "Maccabee" or "Maccabeus" would later be used as an honorific for Judas's brothers as well.[20]

Judas's campaign in the countryside became a full-scale revolt. Maccabean forces employed guerrilla tactics emphasizing speed and mobility. While less trained and under-equipped for pitched battles, the Maccabees could control which battles they took and retreat into the wilderness when threatened. They defeated two minor Seleucid forces at the Battle of the Ascent of Lebonah in 167 BCE and the Battle of Beth Horon in 166 BCE. Toward the end of summer in 165 BCE, Antiochus IV departed for Babylonia in the eastern half of his empire, and left Lysias in charge of the western half as regent. Shortly afterward, the Maccabees won a more substantial victory at the Battle of Emmaus. The factions attempted to negotiate a compromise, but failed; a large Seleucid army was sent to quash the revolt. After the Battle of Beth Zur in 164 BCE as well as news of the death of Antiochus IV in Persia, the Seleucid troops returned to Syria.[21] The Maccabees entered Jerusalem in triumph. They ritually cleansed the Second Temple, reestablishing traditional Jewish worship there; 25 Kislev, the date of the cleansing in the Hebrew calendar, would later become the date when the festival of Hanukkah begins. Regent Lysias, preoccupied with internal Seleucid affairs, agreed to a political compromise that revoked Antiochus IV's ban on Jewish practices. This proved a wise decision: many Hellenized Jews had cautiously supported the revolt due to the suppression of their religion.[22] With the ban retracted, their religious goals were accomplished, and the Hellenized Jews could more easily be potential Seleucid loyalists again. The Maccabees did not consider their goals complete, however, and continued their campaign for a starker break from Greek influence and full political independence. The rebels suffered a loss of support from moderates as a result.[22][23]

Continued struggle (163–160 BCE)

[edit]With the rebels now in control of most of Jerusalem and its environs, a second phase of the revolt began. The rebellion had additional resources, but also additional responsibilities. Rather than being able to retreat to the mountains, the rebels now had territory to defend; abandoning cities would leave their loyalists open to reprisals if the pro-Seleucid forces were allowed to take control again. As such, they focused on being able to win open battles, with additional trained heavy infantry. A civil struggle of low-level violence, reprisals, and murders arose in the countryside, especially in more distant areas where Jewish people were in the minority.[24] Judas launched expeditions to these regions outlying Judea to fight non-Jewish Idumeans, Ammonites, and Galileans. He recruited devout Jews and sent them into Judea to concentrate his allies where they could be protected, although this influx of refugees would soon create food scarcity issues in the land the Maccabees held.[25]

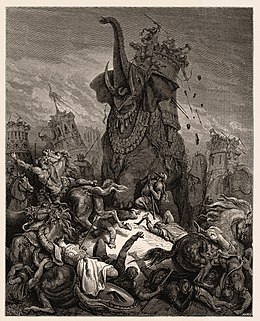

In 162 BCE, Judas began a long siege of the fortified Acra citadel in Jerusalem, still controlled by Seleucid loyalist Jews and a Greek garrison. Regent Lysias, having dealt with rivals back in Antioch, returned to Judea with an army to aid the Seleucid forces. The Seleucids besieged Beth-Zur and took it without a fight, as it was a fallow year and food supplies were meager.[26] They battled Judas's forces in an open fight at the Battle of Beth Zechariah next, with the Seleucids defeating the Maccabees. Judas's younger brother Eleazar Avaran died in battle after bravely attacking a war elephant and being crushed.[26] Lysias's army next besieged Jerusalem. With supplies of food short on both sides and reports of a political rival returning from the eastern provinces to Antioch, Lysias decided to sign an agreement with the rebels and confirm the repeal of the anti-Jewish decrees; the rebels, in return, abandoned their siege of the Seleucid Acra. Lysias and his army then returned to Antioch, with the province officially at peace, but neither the Hellenized Jews nor the Maccabees laid down their arms.[25]

At some point from 163–162 BCE, Lysias ordered the execution of despised High Priest Menelaus as another gesture of reconciliation to the Jews.[27] Shortly afterward, both regent Lysias and 11-year old king Antiochus V were executed after losing a succession struggle with Demetrius I Soter, who became the new Seleucid king. In the winter of late 162 BCE to early 161 BCE, Demetrius I appointed a new high priest, Alcimus, to replace Menelaus and sent an army led by general Bacchides to enforce Alcimus's station. Judas did not give battle, perhaps still rebuilding after his defeat at Beth Zechariah.[28] Alcimus was accepted into Jerusalem, and proved more effective at rallying moderate Hellenists to the pro-Seleucid faction than Menelaus had been. Still, violent tensions between the Maccabees and the Hellenized Jews continued.[29] Bacchides returned to Syria, and a new general, Nicanor, was appointed military governor of Judea. A truce was briefly made between Nicanor and the Maccabees, but was soon broken.[30] Nicanor gained the hatred of the Maccabees after reports surfaced that he had blasphemed in the Temple and threatened to burn it. Nicanor took his forces into the field, and fought the Maccabees first at Caphar-salama, and then at the Battle of Adasa in late winter of 161 BCE. Nicanor was killed early in the fight, and the rest of his army fled afterward.[31]

Judas had been negotiating with the Roman Republic and extracted a vague agreement of potential support. While this would be cause for caution to the Seleucid Empire in the long term, it was not a particular concern in the short term, as the Romans would be unlikely to intervene if the Judean unrest could be decisively crushed.[32]

Battle of Elasa (160 BCE)

[edit]In 160 BCE, Seleucid King Demetrius I went on campaign in the east to fight the rebellious Timarchus. He left his general Bacchides to govern the western part of the empire.[32] Bacchides led an army of 20,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry into Judea on a second expedition intending to reconquer the restive province before it grew too used to autonomy. The size of the rebel army facing them is disputed; 1 Maccabees implausibly claims that Judas's army at Elasa was tiny, with 3,000 men of which only 800–1,000 would fight. Historians suspect the true numbers were larger and possibly as many as 22,000 soldiers, and the author downplayed their strength in an attempt to explain the defeat.[33]

The Seleucid army marched through Judea after carrying out a massacre in the Galilee. This tactic would force Judas to respond in open battle, lest his reputation be damaged by inaction and Alcimus's faction gain strength by claiming he was better positioned to protect the people from future killings. Bacchides advanced toward Jerusalem, while Judas encamped on the rough terrain at Elasa to intercept the Seleucid army. Judas opted to attack the right flank of the Seleucid army hoping to kill the commander, similar to the victory over Nicanor at Adasa. The elite horsemen on the right retreated, and the rebels pursued. This may have been a tactic from Bacchides, however, to feign weakness and draw the Maccabees in where they could be surrounded and defeated, their own retreat cut off. Regardless of whether it was intentional or not, the Seleucids regained their formation and trapped the rebel army with their own left flank. Judas was eventually killed and the remaining Judeans fled.[32]

The Seleucids had reasserted their authority in Jerusalem. Bacchides fortified cities across the land, put allied Greek-friendly Jews in command in Jerusalem, and ensured children of leading families were held as hostages as a guarantee of good behavior. Judas's younger brother Jonathan Apphus (Hebrew: Yonatan) became the new leader of the Maccabees. A new tragedy struck the Hasmonean family when Jonathan's brother John Gaddi was seized and killed while on a mission in Nabatea. Jonathan fought Bacchides and his troops for a time, but the two eventually made a pact for a cease-fire. Bacchides then returned to Syria in 160 BCE.[34]

Autonomy (160–138 BCE)

[edit]

While the Maccabees had lost control of the cities, they seem to have built a rival government in the countryside from 160–153 BCE. The Maccabees avoided direct conflict with the Seleucids, but the internal Jewish civil struggle continued: the rebels harassed, exiled, and killed Jews seen as insufficiently anti-Greek.[35] According to 1 Maccabees, "Thus the sword ceased from Israel. Jonathan settled in Michmash and began to judge the people; and he destroyed the godless out of Israel."[36] The Maccabees were handed an opportunity as the Seleucids broke into infighting in a series of civil wars, the Seleucid Dynastic Wars. The Seleucid rival claimants to the throne needed all their troops elsewhere, and also wished to deny possible allies to other claimants, thus giving the Maccabees leverage. In 153–152 BCE, a deal was struck between Jonathan and Demetrius I. King Demetrius was fending off a challenge from Alexander Balas, and agreed to withdraw Seleucid forces from the fortified towns and garrisons in Judea, barring Beth-Zur and Jerusalem.[35] The hostages were also released. Seleucid control over Judea was weakened, and then weakened further; Jonathan promptly betrayed Demetrius I after Alexander Balas offered an even better deal. Jonathan was granted the title of both High Priest and strategos by Alexander, essentially acknowledging that the Maccabee faction was a more relevant ally to would-be Seleucid leaders than the Hellenist faction.[30] Jonathan's forces fought against Demetrius I, who would die in battle in 150 BCE.[35]

From 152–141 BCE, the rebels achieved a state of informal autonomy akin to a suzerain.[37] The land was de jure part of the Seleucid Empire, but continuing civil wars gave the Maccabees considerable autonomy. Jonathan was given official authority to build and maintain an army in exchange for his aid. During this period, the legitimized armies of Jonathan fought in these civil wars and border struggles to maintain the favor of allied Seleucid leaders.[38] The Seleucids did send an army back into Judea during this period, but Jonathan evaded it and refused battle until it eventually returned to the Seleucid heartland.[39] In 143 BCE, regent Diodotus Tryphon, perhaps eager to reassert control over the restive province, invited Jonathan to a conference. The conference was a trap; Jonathan was captured and executed, despite Jonathan's brother Simon raising the requested ransom and sending hostages. This betrayal led to an alliance between the new leader of the Maccabees, Simon Thassi (Hebrew: Simeon), and Demetrius II Nicator, a rival of Diodotus Tryphon and claimant to the Seleucid throne. Demetrius II exempted Judea from payment of taxes in 142 BCE, essentially acknowledging its independence.[37] The Seleucid settlement and garrison in Jerusalem, the Acra, finally came under Simon's control, peacefully, as did the remaining Seleucid garrison at Beth-Zur. Simon was appointed High Priest around 141 BCE, but he did so by acclamation from the Jewish people rather than appointment by the Seleucid king.[40][37] Both Jonathan and now Simon had maintained diplomatic contact with the Roman Republic; official recognition by Rome came in 139 BCE, as the Romans were eager to weaken and divide the Greek states. This new Hasmonean-Roman alliance was also worded more firmly than Judas Maccabeus's hazy agreement 22–23 years earlier. Continuing strife between rival Seleucid rulers made a government response to formal independence of the new state difficult. New Seleucid King Antiochus VII Sidetes refused an offer of help from Simon's troops while pursuing their mutual enemy Diodotus Tryphon, and made demands for both tribute and for Simon to cede control of the border towns Joppa and Gazara. Antiochus VII sent an army to Judea at some point between 139 and 138 BCE under command of a general named Cendebeus, but it was repulsed.[38]

The Hasmonean leaders did not immediately call themselves "king" or establish a monarchy; Simon called himself merely "nasi" (in Hebrew, "Prince" or "President") and "ethnarch" (in Koine Greek, "Governor").[41][42][43]

Aftermath

[edit]

In 135 BCE, Simon and two of his sons (Mattathias and Judas) were murdered by his son-in-law, Ptolemy son of Abubus, at a feast in Jericho. All five sons of Mattathias were now gone with Simon joining his brothers in death, leaving leadership to the next generation. Simon's third son, John Hyrcanus, became High Priest of Israel.[44] King Antiochus VII would personally invade and besiege Jerusalem in 134 BCE, but after Hyrcanus paid a ransom and ceded the cities of Joppa and Gazara, the Seleucids left peacefully. The conflict ceased, and Hyrcanus and Antiochus VII joined themselves in an alliance, with Antiochus making a respectful donation of a sacrifice at the Temple. For the reprieve and donation, Antiochus VII was referred to as "Eusebes" ("Pious") by the grateful populace.[45] With the suzerainty briefly re-established, Judea sent troops to aid Antiochus VII in his campaigns in Persia. After Antiochus VII's death in 129 BCE, the Hasmoneans ceased offering aid or tribute to the remnants of the declining Seleucid Empire.[46] John Hyrcanus and his children would go on to centralize power more than Simon had done. Hyrcanus's son Aristobulus I called himself "basileus" (king), abandoning pretensions that the High Priest managing political matters was a temporary arrangement.[47][48] The Hasmoneans exiled leaders on the council or gerusia that they felt might threaten their power.[49] The council of elders – which some see as a precursor to the Sanhedrin – ceased to be an independent check on the monarchy.[42][50][51][52] After the success of the Maccabean Revolt, leaders of the Hasmonean dynasty continued their conquest to surrounding areas of Judea, especially under Alexander Jannaeus. The Seleucid Empire was too riven with internal unrest to stop this, and Ptolemaic Egypt maintained largely friendly relations.[53] The Hasmonean court at Jerusalem would not make a sharp break from Hellenic culture and language, and continued with a blend of Jewish traditions and Greek ones.[54][55] They continued to be known by Greek names, would use both Hebrew and Greek on their coinage, and hired Greek mercenaries, but also restored Judaism to a place of primacy in Judea and fostered the new sense of Jewish nationalism that had sprouted during the revolt.[7]

The dynasty would last until 37 BCE, when Herod the Great, making use of heavy Roman support, defeated the last Hasmonean ruler to become a Roman client king.

Tactics and technology

[edit]

Both sides were influenced by Hellenistic army composition and tactics. The basic Hellenistic battle deployment consisted of heavy infantry in the center, mounted cavalry on the flanks, and mobile skirmishers in the vanguard. The most common infantry weapon used was the sarissa, the Macedonian pike. The sarissa was a powerful weapon; it was held in two hands and had great reach (approximately ~6 meters), making it difficult for opponents to approach a phalanx of sarissa-wielding infantry safely. Hellenistic cavalry also used pikes, albeit slightly shorter ones.[56] The Seleucids also had access to trained war elephants imported from India, who sported natural armor in their thick hides and could terrify opposing soldiers and their horses.[57] Rarely, they also made use of scythed chariots.[57]

In terms of army size, the respected historian Polybius reports that in 165 BCE, a military parade near the Seleucid capital Antioch held by Antiochus IV consisted of 41,000 foot soldiers and 4,500 cavalrymen. These soldiers were preparing to fight in an expedition to the east, not in Judea, but give a rough estimate to the total size of the Seleucid forces in the Western part of their empire capable of being deployed wherever the ruler needed them, not including local auxiliaries and garrisons. Antiochus IV appears to have augmented the size of his army by hiring additional mercenaries, at cost to the Seleucid treasury.[58] Most of the forces at that parade would be deployed on matters more important to the Seleucid leadership than suppressing the Judean rebellion, however, and as such only a portion of them likely participated in the battles of the rebellion. They may have been supplemented by local Seleucid-allied militias and garrisons, however.[59]

The Maccabees started as a guerrilla force that likely used the traditional weapons effective in small unit combat in mountainous terrain: archers, slingers, and light infantry peltasts armed with sword and shield. Later writers would romantically portray the Maccabees as ordinary people fighting as irregulars, but the Maccabees did eventually train a standing army similar to the Seleucids, complete with Hellenic-style heavy infantry phalanxes, horse-mounted cavalry, and siege weaponry.[22][60] However, while manufacturing the mostly wooden sarissa would have been easy for the rebels, their body armor was lower quality. They likely used simple leather armor due to a paucity of metals and craftsmen capable of making Greek-style metal armor.[61] It is speculated that diaspora Jews in countries hostile to the Seleucids, such as Ptolemaic Egypt and Pergamon, may have joined the cause as volunteers, bringing their own local talents to the rebel army.[61]

The rebel forces grew with time. There were 6,000 men in Judas's army near the start of the revolt, 10,000 men at the Battle of Beth Zur, and possibly as many as 22,000 soldiers by the time of the defeat at Elasa.[33] In several battles, the rebels may have had numerical superiority to compensate for shortfalls in training and equipment.[62][note 3] After Jonathan was legitimized as high priest and governor by the Seleucid rulers, the Hasmoneans had easier access to recruitment; 20,000 soldiers are reported as repulsing Cendebeus in 139 BCE.[64]

Much of the combat in the revolt took place in hilly and mountainous terrain, which complicated warfare.[65] Seleucid phalanxes trained for mountain combat would fight at somewhat greater distance from each other compared to packed lowland formations, and used slightly shorter but more maneuverable Roman-style pikes.[66]

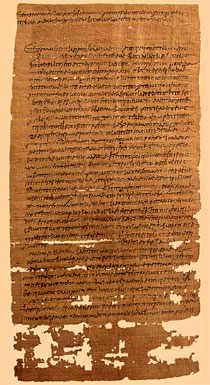

Writings

[edit]Original histories

[edit]The most detailed contemporaneous writings that survived were the deuterocanonical books of First Maccabees and Second Maccabees, as well as Josephus's The Jewish War and Book XII and XIII of Jewish Antiquities.[67] The authors were not disinterested parties; the authors of the books of Maccabees were favorable to the Maccabees, portraying the conflict as a divinely sanctioned holy war and elevating the stature of Judas and his brothers to heroic levels.[22] In comparison, Josephus did not want to offend Greek pagan readers of his work, and is ambivalent toward the Maccabees.[68][69]

The book of 1 Maccabees is considered mostly reliable, as it was seemingly written by an eyewitness early in the reign of the Hasmoneans, most likely during John Hyrcanus's reign. Its depictions of battles are detailed and seemingly accurate, although it portrays implausibly large numbers of Seleucid soldiers, to better emphasize God's aid and Judas's talents.[62][70] The book also acts as Hasmonean dynasty propaganda in its editorial slant on events.[71][72][73] The new rule of the Hasmoneans was not without its own internal enemies; the office of High Priest had been occupied for generations by a descendant of the High Priest Zadok. The Hasmoneans, while of the priestly line (Kohens), were seen by some as usurpers, did not descend from Zadok, and had taken the office originally only via a deal with a Seleucid king. As such, the book emphasizes that the Hasmoneans' actions were in line with heroes of older scripture; they were God's new chosen and righteous rulers. For example, it dismisses a defeat suffered by other commanders named Joseph and Azariah as because "they did not listen to Judas and his brothers. But they did not belong to the family of those men through whom deliverance was given to Israel."[74][71]

2 Maccabees is an abridgment by an unknown Egyptian Jew of a lost five-volume work by an author named Jason of Cyrene. It is a separate work from 1 Maccabees and not a continuation of it. 2 Maccabees has a more directly religious focus than 1 Maccabees, crediting God and divine intervention for events more prominently than 1 Maccabees; it also focuses personally on Judas rather than other Hasmoneans. It has a special focus on the Second Temple: the controversies over the position of High Priest, its pollution by Menelaus into a Greek-Jewish mix, its eventual cleansing, and the threats by Nicanor at the Temple.[75] 2 Maccabees also represents an attempt to take the cause of the Maccabees outside Judea, as it encourages Egyptian Jews and other diaspora Jews to celebrate the cleansing of the temple (Hanukkah) and revere Judas Maccabeus.[75][69] In general, 2 Maccabees portrays the prospects of peace and cooperation more positively than 1 Maccabees. In 1 Maccabees, the only way for the Jews to honorably make a deal with the Seleucids involved first defeating them militarily and attaining functional independence. In 2 Maccabees, intended for an audience of Egyptian Jews who still lived under Greek rule, peaceful coexistence was possible, but misunderstandings or troublemakers forced the Jews into defensive action.[76][77]

Josephus wrote over two centuries after the revolt, but his friendship with the Flavian dynasty Roman emperors meant he had access to resources undreamt of by other scholars. Josephus appears to have used 1 Maccabees as one of his main sources for his histories, but supplements it with knowledge of events of the Seleucid Empire from Greek histories as well as unknown other sources. Josephus seems to be familiar with the work of historians Polybius and Strabo, as well as the mostly lost works of Nicolaus of Damascus.[78][45][79]

Daniel

[edit]The Book of Daniel appears to have been written during the early stages of the revolt around 165 BCE, and would eventually be included in the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament.[note 4] While the setting of the book is 400 years earlier in Babylon, the book is a literary response to the situation in Judea during the revolt (Sitz im Leben); the writer chose to move the setting either for esoteric reasons or to evade scrutiny from would-be censors. It urges its readers to remain steadfast in the face of persecution. For example, Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar orders his court to eat the king's rich food; the prophet Daniel and his companions keep kosher and eat a diet of vegetables and water, yet emerge healthier than all the king's courtiers.[81] The message is clear: defy Antiochus's decree and keep Jewish dietary law. Daniel predicts the king will go insane; Antiochus's title, "Epiphanes" ("Chosen of God"), was mocked by his enemies as "Epimanes" ("Madman"), and he was known to keep odd habits. When Daniel and the Jews are threatened with death, they face it calmly, and are saved in the end, a relevant message among Jewish opposition to Antiochus IV.[82][83]

The final chapters of the book of Daniel include apocalyptic visions of the future. One of the motives for the author was to give heart to devout Jews that their victory was foreseen by prophecy 400 years earlier.[84] Daniel's final vision refers to Antiochus Epiphanes as the "king of the north" and describes his earlier actions, such as being repelled and humiliated by the Romans in his second campaign in Egypt, but also that the king of the north would "meet his end".[82] Additionally, all those who had died under the king of the north would be revived, with those who suffered rewarded while those who had prospered would be subjected to shame and contempt.[2] The main historical items taken away from Daniel is in its depiction of the king of the north desecrating the temple with an abomination of desolation, and stopping the tamid, the daily sacrifice at the Temple; these agree with the depictions in 1 and 2 Maccabees of the changes at the Second Temple.[82][85]

Related works

[edit]Other works appear to have at least been influenced by the Maccabean Revolt include the Book of Judith, the Testament of Moses, and parts of the Book of Enoch. The Book of Judith is a historical novel that describes Jewish resistance against an overwhelming military threat. While the parallels are not as stark as Daniel, some of its depictions of oppression seem influenced by Antiochus's persecution, such as General Holofernes demolishing shrines, cutting down sacred groves, and attempting to destroy all worship other than of the king. Judith, the story's heroine, also bears the feminine form of the name "Judas".[86] The Testament of Moses, similar to the Book of Daniel, provides a witness to Jewish attitudes leading up to the revolt: it describes persecution, denounces impious leaders and priests as collaborators, praises the virtues of martyrdom, and predicts God's retribution upon the oppressors. The Testament is usually considered to have been written in the first century CE, but it is at least possible it was written much earlier, in the Maccabean or Hasmonean era, and then appended onto with first century CE updates. Even if it was entirely written in the first century CE, it was still likely influenced by the experience of Antiochus IV's reign.[87][88] The Book of Enoch's early chapters were written around 300–200 BCE, but new sections were appended over time invoking the authority of Enoch, the great-grandfather of Noah. One section, the "Apocalypse of Weeks", is hypothesized to have been written around 167 BCE, just after Antiochus's persecution began.[89] Similar to Daniel, after the Apocalypse of Weeks recounts world history up to the point of the persecution, it predicts that the righteous will eventually triumph, and encourages resistance.[90] Another section of Enoch, the "Book of Dreams", was likely written after the Revolt had at least partially succeeded; it portrays the events of the revolt in the form of prophetic dream visions.[91]

A more uncertain work that has nevertheless attracted much interest is the Qumran Habakkuk Commentary, part of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The Qumran religious community was not on good terms with the Hasmonean religious establishment in Jerusalem, and is believed to have favored the Zadokite line of succession to the High Priesthood. The commentary (pesher) describes a situation wherein a "Righteous Teacher" is unfairly driven from their post and into exile by a "Wicked Priest" and a "Man of the Lie" (possibly the same person). Many figures have been proposed as the identity of the people behind these titles; one theory goes that the Righteous Teacher was whoever held the High Priest position after Alcimus's death in 159 BCE, perhaps a Zadokite. If this person even existed, they lost their position after Jonathan Apphus, backed by his Maccabee army and his new alliance with Seleucid royal claimant Alexander Balas, took over the High Priest position in 152 BCE. Thus, the Wicked Priest would be Jonathan, and the Qumran community of the era would have consisted of religious opposition to the Hasmonean takeover: the first Essenes. The date of the work is unknown, and others scholars have proposed different candidates as possible identities of the Wicked Priest, so the identification with Jonathan is only a possibility, yet an intriguing and plausible one.[92][93]

Later analysis and historiography

[edit]In the First and Second Books of the Maccabees, the Maccabean Revolt is described as a collective response to cultural oppression and national resistance to a foreign power. Written after the revolt was complete, the books urged unity among the Jews; they describe little of the Hellenizing faction other than to call them lawless and corrupt, and downplay their relevance and power in the conflict.[72][94] While many scholars still accept this basic framework, that the Hellenists were weak and dependent on Seleucid aid to hold influence, this view has since been challenged. In the revisionist view, the heroes and villains were both Jews: a majority of the Jews cautiously supported Hellenizing High Priest Menelaus; Antiochus IV's edicts only came about due to pressure from Hellenist Jews; and the revolt was best understood as a civil war between traditionalist Jews in the countryside and Hellenized Jews in the cities, with only occasional Seleucid intervention.[95][96][97] Elias Bickerman is generally credited as popularizing this alternative viewpoint in 1937, and other historians such as Martin Hengel have continued the argument.[98][85] For example, Josephus's account directly blames Menelaus for convincing Antiochus IV to issue his anti-Jewish decrees.[23][99] Alcimus, Menelaus's replacement as High Priest, is blamed for instigating a massacre of devout Jews in 1 Maccabees, rather than the Seleucids directly.[23] The Maccabees themselves fight and exile Hellenists as well, most clearly in the final expulsion from the Acra, but also in the earlier countryside struggles against the Tobiad clan of Hellenist-friendly Jews.[19]

In general, scholarly opinion is that Hellenistic historians were biased, but also that the bias did not result in excessive distortion or fabrication of facts, and they are mostly reliable sources once the bias is removed.[100] There exist revisionist scholars who are inclined to discount the reliability of the primary histories more aggressively, however.[101] Daniel R. Schwartz argues that Antiochus IV's initial attacks on Jerusalem from 168–167 BCE were not out of pure malice, as 1 Maccabees depicts, or a misunderstanding as 2 Maccabees depicts (and most scholars accept), but rather suppressing an authentic rebellion whose members were lost to history, as the Hasmoneans wished to show only themselves as capable of bringing victory.[11] Sylvie Honigman argues that the depictions of Seleucid religious oppression are misleading and likely false. She advances the view that the loss of civil rights by the Jews in 168 BCE was an administrative punishment in the aftermath of local unrest over increased taxes; that the struggle was fundamentally economic, and merely interpreted as religiously driven in retrospect.[85] She also argues that the moralistic slant of the sources means that their depictions of impious acts by Hellenists cannot be trusted as historical. For example, the claim that Menelaus stole temple vessels to pay for a bribe to Antiochus is merely aimed at delegitimizing them both.[102] John Ma argues that the Temple was restored in 164 BCE upon petition by Menelaus to Antiochus, not liberated and rededicated by the Maccabees.[76] These views have attracted partial support, but have not become a new consensus themselves. Modern defenders of more direct readings of the sources cite that evidence of such an unrecorded popular rebellion is thin-to-nonexistent. Assuming that Antiochus IV would not have started an ethno-religious persecution for irrational reasons is an ahistorical position in this criticism, as many leaders both ancient and modern clearly were motivated by religious concerns.[85][103]

Later scholars and archaeologists have found and preserved various artifacts from the time period and analyzed them, which have informed historians on the plausibility of various elements in the books.[68] For recent examples, a stele (the "Helidorus stele") was discovered and deciphered in 2007 that dated from around 178 BCE, and gives insight to Seleucid government appointments and policy in the era immediately preceding the revolt.[104][105] The Givati Parking Lot dig in Jerusalem from 2007–2015 has found possible evidence of the Acra; it might resolve a seeming contradiction between Josephus's account of the Acra's fate (he claimed it was torn down) and 1 Maccabees's account (it was merely occupied) in favor of the 1 Maccabees version.[106][107]

Legacy

[edit]

The Jewish festival of Hanukkah celebrates the rededication of the Temple following Judas Maccabeus's victory over the Seleucids.[108] According to rabbinic tradition, the victorious Maccabees could only find a small jug of oil that had remained pure and uncontaminated by virtue of a seal, and although it only contained enough oil to sustain the Menorah for one day, it miraculously lasted for eight days, by which time further oil had been procured. During the era of the Hasmonean kingdom, Hanukkah was observed prominently; it acted as a "Hasmonean Independence Day" to commemorate the success of the revolt and the legitimacy of the Hasmonean rulers.[109] Diaspora Jews celebrated it as well, fostering a sense of Jewish collective identity: it was a liberation day for all Jews, not merely Judean Jews.[note 5][111] As a result, Hanukkah outlasted Hasmonean rule, although its importance receded as time passed. Hanukkah would gain new prominence in the 20th century and rekindle interest in its origins in the Maccabees.[112]

The Jewish victory at the Battle of Adasa led to an annual festival as well, albeit one less prominent and remembered than Hanukkah. The defeat of Seleucid general Nicanor is celebrated on 13 Adar as Yom Nicanor.[113][114]

The traumatic time period helped define the genre of the apocalypse and heightened Jewish apocalypticism.[115] The portrayal of an evil tyrant like Antiochus IV attacking the holy city of Jerusalem in the Book of Daniel became a common theme during later Roman rule of Judea, and would contribute to Christian conceptions of the Antichrist.[116]

The persecution of the Jews under Antiochus, and the Maccabees response, would influence and create new trends in Jewish strains of thought with regard to divine rewards and punishments. In earlier Jewish works, devotion to God and adherence to the law led to rewards and punishments in life: the observant would prosper, and disobedience would result in disaster. The persecution of Antiochus IV directly contradicted this teaching: for the first time, Jews were suffering precisely because they refused to violate Jewish law, and thus the most devout and observant Jews were the ones suffering the most. This resulted in literature suggesting that those who suffered in their earthly life would be rewarded afterward, such as the Book of Daniel describing a future resurrection of the dead, or 2 Maccabees describing in detail the martyrdom of a woman and her seven sons under Antiochus, but who would be rewarded after their deaths.[117][118][119]

As a victory of the "few over the many", the revolt served as inspiration for future Jewish resistance movements, such as the Zealots.[120] The most famous of these later revolts are the First Jewish–Roman War in 66–73 CE (also called the "Great Revolt") and the Bar Kochba revolt from 132 to 136 CE.[116][121] After the failure of these revolts, Jewish interpretation of the Maccabean Revolt became more spiritual; it instead focused on stories of Hanukkah and God's miracle of the oil, rather than practical plans for an independent Jewish polity backed by armed might. The Maccabees were also discussed less as time went on; they appear only rarely in the mishnah, the writings of the Tannaim, after these Jewish defeats.[122][123][124] Rabbinical displeasure with the later rule of the Hasmoneans after the revolt also contributed to this; even when stories were explicitly set during the Maccabean period, references to Judas by name were explicitly removed to avoid hero-worship of the Hasmonean line.[125] The books of Maccabees were downplayed and relegated in the Jewish tradition and not included in the Jewish Tanakh (Hebrew Bible); it would be Christians who would produce more art and literature referencing the Maccabees during the medieval era, as the books of Maccabees were included in the Catholic and Orthodox Biblical canon.[112] Medieval Christians during the Carolingian era esteemed the Maccabees as early examples of chivalry and knighthood, and the Maccabees were invoked in the later Middle Ages as holy warriors to emulate during the Crusades.[126][127] In the 14th century, Judas Maccabeus was included in the Nine Worthies, medieval exemplars of chivalry for knights to model their conduct on.

The Jewish downplaying of the Maccabees would be challenged centuries later in the 19th century and early 20th century, as Jewish writers and artists held up the Maccabees as examples of independence and victory.[128] Proponents of Jewish nationalism of that era saw past events, such as the Maccabees, as a hopeful suggestion to what was possible, influencing the nascent Zionist movement. A British Zionist organization formed in 1896 is named the Order of Ancient Maccabeans, and the Jewish sporting organization Maccabi World Union names itself after them.[129][note 6] The revolt is featured in plays of the playwrights Aharon Ashman, Ya'akov Cahan, and Moshe Shamir. Various organizations in the modern state of Israel name themselves after the Maccabees and the Hasmoneans or otherwise honor them.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The date of the treasury raid is disputed. 1 Maccabees suggests the Temple treasury was raided in 169 BCE after the first expedition to Egypt. 2 Maccabees suggests the treasury was raided in 168 BCE after the second expedition to Egypt. Possibly, the Book of Daniel (Daniel 11:28–11:30) suggests Antiochus IV raided Jerusalem twice, after each trip. Josephus says Antiochus IV visited Jerusalem twice and looted the city the first time, the Temple the second time.[11]

- ^ 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees are both sources heavily slanted against the Seleucids and in favor of the Maccabees, so historians such as Lester L. Grabbe caution that the outrages described within them should be taken with some skepticism. Nevertheless, it is clear enough that whatever actions the Seleucids did take were sufficient to enrage the populace, even if they were later exaggerated.[2]

- ^ Historian Bezalel Bar-Kochva propounds the view that the Seleucid army was a small but elite force that largely consisted of high-morale Greeks devoted to maintaining "their" empire, hence his writings that the rebels likely outnumbered the Seleucids despite the Books of Maccabees claiming otherwise. That said, the matter is not settled; other scholars such as Israel Shatzman keep to the older view that the Seleucids deployed a larger but less disciplined force with many non-Greek soldiers with low morale, fighting only for money and with little care for the Seleucid cause.[63]

- ^ The nature of Chapters 1–6 of Daniel is contested; some scholars believe that these chapters existed prior to the Revolt and were lightly modified at most, while others suggest that such reliance on pre-existing legends of Daniel was minor.[80]

- ^ The degree to which diaspora Jews celebrated Hanukkah in the centuries after the revolt but before the medieval age is unclear and disputed, however. The main surviving somewhat contemporary Jewish source mentioning Hanukkah outside Judea is Josephus, who as a distant relation to the Hasmonean family line and who grew up in Jerusalem, would be more inclined to play up its importance.[110]

- ^ The Maccabi World Union organizes the Maccabiah Games, first held in 1932. Commentators have noted the irony of naming an Olympics-style sporting competition, whose origin was from ancient Greece, after a group that explicitly fought Greek influence.[42]

References

[edit]- ^ Grabbe 2008, p. 278-281

- ^ a b c d e Grabbe 2010, p. 10–16

- ^ Grabbe 2008, p. 65-68; 305-306

- ^ Hengel 1973, p. 64

- ^ Grabbe 2008, p. 144-146

- ^ a b Cohen 1988, p. 46–53

- ^ a b Regev 2013, p. 17–25

- ^ Bar-Kochva, Bezalel (2010). The Image of the Jews in Greek Literature: The Hellenistic Period. University of California Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780520290846.

- ^ a b Hengel 1973, p. 277

- ^ Tcherikover 1959, p. 170–190

- ^ a b Schwartz, Daniel R. (2001). "Antiochus IV Epiphanes in Jerusalem". Historical Perspectives: From the Hasmoneans to Bar Kokhba in Light of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. p. 45–57. ISBN 90-04-12007-6.

- ^ Grainger 2012, p. 25–29

- ^ Hengel 1973 p. 280–281; 286–297.

- ^ Cohen 1988, p. 37–39

- ^ Josephus, Flavius (2017) [c. 75]. The Jewish War. Translated by Hammond, Martin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-964602-9.

- ^ Honigman 2014, p. 388–389. Honigman downplays strongly the claims of actual religious persecution, however.

- ^ a b Grainger 2012, p. 32–36

- ^ Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 194–198.

- ^ a b Honigman 2014, p. 282–284

- ^ Grainger 2012, p. 17

- ^ Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 276–282.

- ^ a b c d Grabbe 2010, p. 67–68

- ^ a b c Mendels 1997, p. 119–129

- ^ Regev 2013, p. 273–274

- ^ a b Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 342–346

- ^ a b Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 335–339

- ^ Mendels 1997, p. 129

- ^ Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 348–350

- ^ Scolnic 2004, p. 12–36

- ^ a b Tcherikover 1959, p. 230–233

- ^ Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 359–361

- ^ a b c Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 376–402

- ^ a b Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 47–62

- ^ Schürer 1896, p. 235–238

- ^ a b c Schürer 1896, p. 239–242

- ^ 1 Maccabees 9:73

- ^ a b c Tcherikover 1959, p. 236–240

- ^ a b Mendels 1997, p. 174–179

- ^ Schürer 1896, p. 251

- ^ Honigman 2014, p. 163

- ^ Schürer 1896, p. 265

- ^ a b c Spiro, Ken (2001). "History Crash Course #29: Revolt of the Maccabees". Aish HaTorah. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Regev 2013, p. 115–117. Regev translates "Nasi" as "King", however, and credits Simon with less restraint than other authors, though he acknowledges the different terms.

- ^ Schürer 1896, p. 271–273

- ^ a b Rajak, Tessa (1980). "Roman Intervention in a Seleucid Siege of Jerusalem?". The Jewish Dialogue with Greece and Rome. Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 81–98. doi:10.1163/9789047400196_010. ISBN 978-90-47-40019-6. Alternate location: Rajak, Tessa (March 1981). "Roman Intervention in a Seleucid Siege of Jerusalem?". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 22 (1): 65–81. Rajak hypothesizes a Roman intervention to explain Antiochus VII's seeming change of heart.

- ^ Mendel 1997, p. 180–181

- ^ Regev 2013, p. 165–172

- ^ Mendels 1997, p. 62

- ^ "GERUSIA - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com.

- ^ "GOVERNMENT - JewishEncyclopedia.com". jewishencyclopedia.com.

- ^ Cohen 1988, p. 123–125

- ^ Mantel, Hugo (1961). Studies in the History of the Sanhedrin. Harvard Semitic Series. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 49–50, 62–63. LCCN 61-7391. Note that Mantel himself is skeptical of the claimed connection between the gerusia and the Sanhedrin, and attributes it to Salomo Sachs and Elias Bickerman.

- ^ Tcherikover 1959, p. 246–255

- ^ Hengel, Martin (1980) [1976]. Jews, Greeks and Barbarians: Aspects of the Hellenization of Judaism in the pre-Christian Period. Translated by Bowden, John. Fortress Press. p. 114–117. ISBN 0-8006-0647-7.

- ^ Schwartz, Seth (2001). Imperialism and Jewish Society, 200 B.C.E. to 640 C.E. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. p. 33–36. ISBN 0-691-08850-0.

- ^ Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 8–14

- ^ a b Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 16–19

- ^ Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 30–36

- ^ Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 40–43

- ^ Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 68–75

- ^ a b Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 85–89. Note that historian Israel Shatzman directly doubts Bar-Kochva's suggestion of diaspora Jews providing training to the Maccabees, suspecting Jews trained as mercenaries abroad would have been more likely to aid the Seleucids instead (Shatzman 1991, p. 19).

- ^ a b Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 63–67

- ^ Mendels 1997, p. 167.

- ^ Shatzman 1991, p. 29–31

- ^ Shatzman 1991, p. 12, 310

- ^ Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 116-127

- ^ Bickerman 1937, p. 9

- ^ a b Regev 2013, p. 25–30

- ^ a b Bickerman 1937, p. 22–23

- ^ Shatzman 1991, p. 26

- ^ a b Harrington 1988, p. 57–59

- ^ a b Bickerman 1937, p.17–21

- ^ Honigman 2014, p. 6–7

- ^ 1 Maccabees 5:60–5:62

- ^ a b Harrington 1988, p. 36–56

- ^ a b Doran, Robert (2016). "Resistance and Revolt. The Case of the Maccabees.". In Collins, John J.; Manning, J. G. (eds.). Revolt and Resistance in the Ancient Classical World and the Near East: In the Crucible of Empire. Brill. pp. 175–178, 186–187. ISBN 978-90-04-33017-7.

- ^ Schwartz 2008, p. 48–50

- ^ Harrington 1988, p. 109

- ^ Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 191

- ^ Grabbe 2020, p. 88–91

- ^ Portier-Young 2011, p. 211–212

- ^ a b c Harrington 1988, p. 17–35

- ^ Portier-Young 2011, p. 258–262

- ^ Portier-Young 2011, p. 41

- ^ a b c d Collins, John J. (2016). "Temple or Taxes: What Sparked the Maccabean Revolt?". In Manning, J. G. (ed.). Revolt and Resistance in the Ancient Classical World and the Near East: In the Crucible of Empire. Brill. pp. 189–201. doi:10.1163/9789004330184_013. ISBN 978-90-04-33017-7.

- ^ Harrington 1988, p. 114–119

- ^ Harrington 1988, p. 110–114

- ^ Portier-Young 2011, p. 391

- ^ Portier-Young 2011, p. 317–319

- ^ Portier-Young 2011, p. 314–345

- ^ Portier-Young 2011, p. 346–352. Portier-Young suggests 165–160 BCE for a more specific guess as to the date of authorship of the Book of Dreams on p. 388, but the matter is disputed.

- ^ Eshel, Hanan (February 2008). The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Hasmonean State. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdsmans Publishing Company. p. 27–61. ISBN 9780802862853.

Appointed high priest in 152 BCE, he [Jonathan] was probably the figure designated by the Qumran authors as 'the wicked priest.'

- ^ Harrington 1988, p. 119–123

- ^ Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 302

- ^ Hengel 1973, p. 290

- ^ Schultz, Joseph P. (1981). Judaism and the Gentile Faiths: Comparative Studies in Religion. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 155. ISBN 0-8386-1707-7.

- ^ Honigman 2014, p. 383–385

- ^ Scolnic 2004, p. 2

- ^ Josephus, Flavius (1943) [c. 93]. "Book XII, 12.383-385". Jewish Antiquities. Translated by Marcus, Ralph. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 199–201. ISBN 0-674-99577-5.

For Lysias had advised the king to slay Menelaus, if he wished the Jews to remain quiet and not give him any trouble; it was this man, he said, who had been the cause of the mischief by persuading the king's father to compel the Jews to abandon their father's religion.

- ^ Mendels 1997, p. 4

- ^ Linda Zollschan, "Review of Sylvie Honigman, 'Tales of High Priests and Taxes'", in Bryn Mawr Classical Review, 2015.08.07

- ^ Hongiman 2014, p. 3–4; 20–21; 91–93; 227

- ^ Mendels, Doron (2021). "1 Maccabees". In Oegema, Gerbern S. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Apocrypha. Oxford University Press. pp. 150–168. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190689643.013.9. ISBN 978-0-19-068966-7. Mendels also cites:

Bar-Kochva, Bezalel (2016). "The Religious Persecutions of Antiochus Epiphanes as a Historical Reality". Tarbiz (in Hebrew). 84 (3): 295–344. JSTOR 24904720. - ^ Barkat, Amiram (May 8, 2007). "Ancient Greek Inscription, Dating to 178 B.C.E., Goes on Display at Israel Museum". Haaretz. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Portier-Young 2011, p. 80–82

- ^ Lawler, Andrew (April 22, 2016). "Jerusalem Dig Uncovers Ancient Greek Citadel". National Geographic. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ The Middle Maccabees: Archaeology, History, and the Rise of the Hasmonean Kingdom. The Society of Biblical Literature. 2021. ISBN 978-0884145042.

- ^ Farmer 1956, p. 132–145

- ^ Regev 2013, p. 50–57

- ^ Schwartz 2008, p. 37, 87

- ^ Regev 2013, p. 278–279

- ^ a b Harrington 1988, p. 131

- ^ Bar-Kochva 1989, p. 372

- ^ Farmer 1956, p. 145–155

- ^ Portier-Young 2011, xxi–xxiii; 3–5

- ^ a b Hengel 1973, p. 306

- ^ Cohen 1988, p. 105–108

- ^ Grabbe 2010, p. 94

- ^ Ehrman, Bart (2020). Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife. Simon & Schuster. p. 142–146; 151–158. ISBN 9781501136757.

- ^ Farmer 1956, p. 175–179; 203

- ^ Mendels 1997, p. 371–376

- ^ Stemberger, Günter (1992). "The Maccabees in Rabbinic Tradition". The Scriptures and the Scrolls: Studies in Honour of A.S. van der Woude on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday. E. J. Brill. p. 192–203.

- ^ Bickerman 1937, p. 100

- ^ Farmer 1956, p. 126–128

- ^ Noam, Vered (2018). Shifting Images of the Hasmoneans: Second Temple Legends and Their Reception in Josephus and Rabbinic literature. Translated by Ordan, Dena. Oxford University Press. p. 219–221. ISBN 978-0-19-881138-1.

- ^ Signori, Gabriela (2012). Dying for the Faith, Killing for the Faith: Old-Testament Faith-Warriors (1 and 2 Maccabees) in Historical Perspective. Brill. p. 12–20. ISBN 978-90-04-21104-9.

- ^ Dunbabin, Jean (1985). "The Maccabees as Exemplars in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries". Studies in Church History: Subsidia. 4: 31–41. doi:10.1017/S0143045900003549.

- ^ Arkush, Allan (December 4, 2018). "In Memory of Judah Maccabee". The Jewish Review of Books. New York. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ Skolnik, Fred, ed. (2007). "Maccabi World Union; Order of Ancient Maccabaeans". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 13 (Second ed.). Macmillan Reference USA.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bar-Kochva, Bezalel (1989). Judas Maccabaeus: The Jewish Struggle Against the Seleucids. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521323525.

- Bickerman, Elias (1979) [1937]. The God of the Maccabees: Studies on the Meaning and Origin of the Maccabean Revolt. Translated by Moehring, Horst R. Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-05947-4.

- Cohen, Shaye J. D. (November 2014) [1988]. From the Maccabees to the Mishnah, Third Edition. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23904-6.

- Farmer, William Rueben (1956). Maccabees, Zealots, and Josephus: An Inquiry into Jewish Nationalism in the Greco-Roman period. New York: Columbia University Press. LCCN 56-7364.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2008). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period: The Coming of the Greeks: The Early Hellenistic Period (335–175 BCE). Library of Second Temple Studies 68. Vol. 2. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-03396-3.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2010). An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel, and Jesus. Continuum. ISBN 9780567552488.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2020). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period: The Maccabean Revolt, Hasmonaean Rule, and Herod the Great (174–4 BCE). Library of Second Temple Studies. Vol. 95. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-5676-9294-8.

- Grainger, John D. (2012). The Wars of the Maccabees. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 9781781599464.

- Harrington, Daniel J. (2009) [1988]. The Maccabean Revolt: Anatomy of a Biblical Revolution. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-60899-113-6.

- Hengel, Martin (1974) [1973]. Judaism and Hellenism: Studies in Their Encounter in Palestine During the Early Hellenistic Period (1st English ed.). London: SCM Press. ISBN 0334007887.

- Honigman, Sylvie (2014). Tales of High Priests and Taxes: The Books of the Maccabees and the Judean Rebellion against Antiochos IV. Oakland, California: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520958180.

- Mendels, Doron (1997) [1992]. The Rise and Fall of Jewish Nationalism. Jewish and Christian Ethnicity in Ancient Palestine. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8028-4329-8.

- Portier-Young, Anathea (2011). Apocalypse Against Empire: Theologies of Resistance in Early Judaism. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802870834.

- Regev, Eyal (2013). The Hasmoneans: Ideology, Archaeology, Identity. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-55043-4.

- Schürer, Emil (1896) [1890]. A History of the Jewish People in the Times of Jesus Christ. Translated by MacPherson, John. Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 1565630491. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- Schwartz, Daniel R. (2008). 2 Maccabees. Commentaries on Early Jewish Literature. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-019118-9.

- Scolnic, Benjamin (2004). Alcimus, Enemy of the Maccabees. University Press America, Inc. ISBN 0-7618-3044-8.

- Shatzman, Israel (1991). The Armies of the Hasmonaeans and Herod: From Hellenistic to Roman Frameworks. Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism. Vol. 25. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 3-16-145617-3.

- Tcherikover, Victor (1959). Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews. Translated by Applebaum, S. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America.

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Akiba ben Joseph, (born ad 40—died c. 135, Caesarea, Palestine), Jewish sage, one of the founders of rabbinic Judaism. He is said to have been an illiterate shepherd who began to study after age 40. He believed that Scripture contained many implied meanings in addition to its overt meaning, and he regarded written law (Torah) and oral law (Halakhah) as ultimately one. He collected and systematized the oral traditions concerning the conduct of Jewish social and religious life, thus laying the foundation of the Mishna. He may have been involved in Bar Kokhba’s unsuccessful rebellion against Rome; he gave the rebel leader his title and recognized him as the messiah. He was imprisoned by the Romans and martyred for his public teaching.

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Rabbi Akiva | |

|---|---|

16th-century illustration | |

| Title | Tanna |

| Personal | |

| Born | c. 50 CE |

| Died | 28 September 135 Caesarea, Judaea, Roman Empire |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Buried | Tiberias, Galilee |

Akiva ben Joseph (Mishnaic Hebrew: עֲקִיבָא בֶּן יוֹסֵף, ʿĂqīḇāʾ ben Yōsēp̄; c. 50 – 28

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Akiva ben Joseph (Mishnaic Hebrew: עֲקִיבָא בֶּן יוֹסֵף, ʿĂqīḇāʾ ben Yōsēp̄; c. 50 – 28 September 135 CE),[1] also known as Rabbi Akiva (רַבִּי עֲקִיבָא), was a leading Jewish scholar and sage, a tanna of the latter part of the first century and the beginning of the second. Rabbi Akiva was a leading contributor to the Mishnah and to Midrash halakha. He is referred to in Tosafot as Rosh la-Hakhamim ("Chief of the Sages").[2] He was executed by the Romans in the aftermath of the Bar Kokhba revolt.

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Akiva ben Joseph (written עֲקִיבָא in the Babylonian Talmud and עֲקִיבָה in the Jerusalem Talmud),[3] born c. 50 CE, was of humble parentage.[4][5] According to some sources, he was descended from converts to Judaism.[6]

When Akiva married the daughter of Ben Kalba Sabuaʿ (בֶּן כַּלְבָּא שָׂבוּעַ),[a] a wealthy citizen of Jerusalem, Akiva was an uneducated shepherd employed by him. The first name of Akiva's wife is not provided in earlier sources, but a later version of the tradition gives it as Rachel.[4][8] She stood loyally by her husband during the period of his late initiation into rabbinic studies after he was 40 years of age,[4] and in which Akiva dedicated himself to the study of Torah.

A different tradition[8] narrates that, at the age of 40, Akiva attended the academy of his native town, Lod, presided over by Eliezer ben Hurcanus. Hurcanus was a neighbour of Joseph, the father of Akiva. The fact that Eliezer was his first teacher, and the only one whom Akiva later designates as "rabbi", is of importance in settling the date of Akiva's birth. These legends set the beginning of his years of study at about 75–80.

Besides Eliezer, Akiva studied under Joshua ben Hananiah[8] and Nachum Ish Gamzu.[9] According to the Jerusalem Talmud, R. Joshua ordained Akiva as his fellow-student, presumably with semikhah.[10] Akiva was on equal footing with Gamaliel II, whom he later met. Rabbi Tarfon was considered as one of Akiva's masters,[11] but the pupil outranked his teacher and he became one of Akiva's greatest admirers.[4][12] Akiva remained in Lod[4][13] as long as Eliezer dwelt there, and then moved his own school to Beneberak.[4][14] Akiva also lived for some time at Ziphron,[15] modern Zafran[16] near Hamath.[17]

Marriage

[edit]According to the Talmud, Akiva was a shepherd for Ben Kalba Sabuaʿ when the latter's daughter noticed his modesty and fine character traits. She offered to marry him if he would agree to begin studying Torah, as at the time he was 40 years old and illiterate. When her father found out she was secretly betrothed[18] to an unlearned man, he was furious. He drove his daughter out of his house, swearing that he would never help her while Akiva remained her husband. Akiva and his wife lived in such poverty that they used straw for their bed. The Talmud relates that once Elijah the prophet assumed the guise of a poor man and came to their door to beg for some straw for a bed for his wife[4] after she had given birth. When Akiva and his wife saw that there were people even poorer than they, Rachel said to him, "Go, and become a scholar".[19]

By agreement with his wife, Akiva spent twelve years away from home, pursuing his studies. He would make a living by cutting wood from the forest, selling half for his wife's and children's wellbeing, and using the other half for keeping a fire burning at night to keep himself warm and to provide light thereby for his own studies.[20] Returning at the end of twelve years accompanied by 12,000 disciples, at the point of entering his home he overheard his wife say to a neighbour who was critical of his long absence: "If I had my wish, he should stay another twelve years at the academy." Without crossing the threshold, Akiva went back to the academy. He returned twelve years later escorted by 24,000 disciples. When his wife went out to greet him, some of his students, not knowing who she was, sought to restrain her.[4] But Akiva exclaimed, "Let her alone; for what is mine and yours, is hers" (she deserves the credit for our Torah study). Not knowing who he was, Ben Kalba Sabuaʿ also approached Akiva and asked him for help annulling his vow to disown his daughter and her husband. Akiva asked him, "Would you have made your vow if you had known that he would become a great scholar?" Ben Kalba Sabuaʿ replied, "Had I known that he would learn even one chapter or one single Halakha, [I would not have made the vow]". Akiva said to him, "I am that man". Ben Kalba Sabuaʿ fell at Akiva's feet and gave him half his wealth.[19][21]

According to another source,[22] Akiva saw that at some future time he would take in marriage the wife of Turnus Rufus (his executioner, also known as Quintus Tineius Rufus) after she converted to Judaism, for which reason he spat on the ground (for having come from a fetid drop), smiled (at her conversion) and wept (at such beauty eventually rotting in the dust after death). The motive behind this marriage is not given.

Later years

[edit]The greatest tannaim of the middle of the second century came from Akiva's school, notably Rabbi Meir, Judah bar Ilai, Simeon bar Yochai, Jose ben Halafta, Eleazar ben Shammua, and Rabbi Nehemiah. Besides these, Akiva had many disciples whose names have not been handed down, but the Aggadah variously gives their number as 12,000,[23] 24,000[21][24] and 48,000.[19]

Akiva is reported to have had a rabbinic relationship with Rabban Gamaliel dated as before their trip to Rome.[25][26] Convinced of the necessity of a central authority for Judaism, Akiva became a devoted adherent and friend of Rabban Gamaliel, who aimed at constituting the patriarch the true spiritual chief of the Jews.[4][27] However, Akiva was just as firmly convinced that the power of the patriarch must be limited both by the written and the oral law, the interpretation of which lay in the hands of the learned; and he was accordingly brave enough to act in ritual matters in Rabban Gamaliel's own house contrary to the decisions of Rabban Gamaliel himself.[4][28] Akiva filled the office of an overseer of the poor.[4][29] Various rabbinic texts testify to his personal qualities, such as benevolence and kindness toward the sick and needy.[30]

In 95–96 CE, Akiva was in Rome,[4][31] and some time before 110 he was in Nehardea.[32] During his travels, it is probable that he visited other places having important Jewish communities.[4][33]

Akiva allegedly took part in the Bar Kokhba revolt of 132–136, but his role here is not historically determined.[4] The only established fact concerning Akiva's connection with Bar Kochba is that he regarded Bar Kochba as the promised Messiah;[34] this is the only evidence of active participation by Akiva in the revolution.[4] Some modern scholars argue that Akiva's thousands of students died fighting for Bar Kochba, but this opinion was first formulated by Nachman Krochmal around 200 years ago and has no earlier source.[35] A baraita[36] states that Akiva suffered martyrdom on account of his transgression of Hadrian's edicts against the practice and the teaching of the Jewish religion, being sentenced to die by Turnus Rufus in Caesarea.[4][37] As this story credits the execution to religious rather than political reasons, it may be evidence against Akiva's having a role in the revolt.[4] Akiva's death occurred after several years of imprisonment,[38] which places it at about 132,[4] before the suppression of the Bar Kochba revolution; otherwise the delay of the Romans in executing him would be quite inexplicable.[39] That the religious interdicts of Hadrian preceded the overthrow of Bar Kochba is shown by the Mekhilta.[40][4]

Jewish sources relate that he was subjected to combing, a Roman torture in which the victim's skin was flayed with iron combs.

Death

[edit]

The death of Akiva is usually rendered as some redacted form of three separate versions of the circumstances. Each version shares the same basic plot points: Akiva defies the Roman prohibition on teaching Torah, the consul Turnus Rufus orders his execution, Akiva is flayed alive, and his final words are the Shema prayer.

The most common version of Akiva's death is that the Roman government ordered him to stop teaching Torah, on pain of death, and that he refused. When Turnus Rufus, as he is called in Jewish sources, ordered Akiva's execution, Akiva is said to have recited his prayers calmly, though suffering agonies; and when Rufus asked him whether he was a sorcerer, since he felt no pain, Akiva replied, "I am no sorcerer; but I rejoice at the opportunity now given to me to love my God 'with all my life,' seeing that I have hitherto been able to love Him only 'with all my means' and 'with all my might.'" He began reciting the Shema, and with the word Echad, "[God is] One!", he expired.[4][41]

The version in the Babylonian Talmud tells it as a response of Akiva to his students, who asked him how he could yet offer prayers to God. He says to them, "All my life I was worried about the verse, 'with all your soul' (and the sages expounded this to signify), even if He takes away your soul. And I said to myself, when will I ever be able to fulfil this command? And now that I am finally able to fulfil it, I should not?" Then he said the Shema and he extended the final word Echad ("One") until his life expired with that word. A heavenly voice went out and announced: "Blessed are you, Rabbi Akiva, that your life expired with Echad".[42]

Another legend is that Elijah bore the body by night to Caesarea. The night, however, was as bright as the finest summer's day. When they arrived, Elijah and Joshua entered a cavern that contained a bed, table, chair, and lamp, and deposited Akiva's body there. No sooner had they left it than the cavern closed of its own accord, so that no one has found it since.[4][43] Rebbe Akiva's modern day tomb is located in Tiberias.[44] Annually, on the night of Lag BaOmer, pilgrims light bonfires at the tomb of Rebbe Akiva. The pilgrims include some from Boston, Massachusetts, a tradition reinstated by the Bostoner Rebbe in 1983.[45]

Religious and scholarly perspectives

[edit]Religious philosophy

[edit]A Tannaitic tradition mentions that of the four who delved into the Pardes (legend), Akiva was the only one who was able to properly absorb this wisdom, with the other three suffering various consequences as a result of the attempt.[46] This serves at least to show how strong in later ages was the recollection of Akiva's philosophical speculation.[4]

The relationship between God and man

[edit]Akiva's opinion about the creation of man is recorded in Pirkei Avot:

- How favoured is man, for he was created after an image; as Scripture says,[47] "for in an image, God made man."[48]

Akiva's ontology is based upon the principle that man was created בצלם, that is, not in the image of God—which would be בצלם אלהים—but after an image, after a primordial type; or, philosophically speaking, after an Idea—what Philo calls in agreement with Judean theology, "the first heavenly man" (see Adam ḳadmon). Strict monotheist that Akiva was, he protested against any comparison of God with the angels, and declared the plain interpretation of כאחד ממנו[49] as meaning "like one of us" to be arrant blasphemy.[4][50] It is quite instructive to read how a Christian of Akiva's generation, Justin Martyr, calls the literal interpretation—thus objected to by Akiva—a "Jewish heretical one".[51] In his earnest endeavours to insist as strongly as possible upon the incomparable nature of God, Akiva indeed lowers the angels somewhat to the realms of mortals, and (alluding to Psalms 78:25) maintains that manna is the actual food of the angels.[4][52] This view of Akiva's, in spite of the energetic protests of his colleague Rabbi Ishmael, became the one generally accepted by his contemporaries.[53][4]

From his views as to the relation between God and man, he deduces that a murderer is to be considered as committing the crime against the divine archetype (דמות) of man.[4][54] Similarly, he recognizes as the chief and greatest principle of Judaism the command, "Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself."[4][55] He does not, indeed, maintain thereby that the execution of this command is equivalent to the performance of the whole Law; and in one of his polemic interpretations of Scripture he protests strongly against a contrary opinion allegedly held by Christians, and other non-Jews since the diaspora, according to which Judaism is at best "simply morality."[4][56] For, in spite of his philosophy, Akiva was an extremely strict and national Jew.[4]

But he is far from representing strict justice as the only attribute of God: in agreement with the ancient Israel theology of the מדת הדין, "the attribute of justice", and מדת הרחמים, "the attribute of mercy,"[4][57] he teaches that God combines goodness and mercy with strict justice.[58] Hence his maxim, referred to above, "God rules the world in mercy, but according to the preponderance of good or bad in human acts."[4]

Eschatology