The Pharisees boldly transferred the atoning power connected with the Day of Atonement from the high priest and the sacerdotal ceremonies in which the high priest functioned to the day itself.

Outside the Temple the influence of the Pharisees was supreme, and even within the Temple itself, which, of course, was under the control of the Sadducean priesthood, the influence of the Pharisees made itself felt in decisive fashion. This influence grew as time went on until, during the last ten or twenty years of the Temple's existence, the direction of its ceremonies was practically under the control of the Pharisees.

In the Mishnah tractate, Yoma, which deals with the ceremonies of the Day of Atonement in the Temple, from the Pharisaic point of view, we are told that seven days before the Day of Atonement the high priest, who was, of course, a Sadducee, went into retreat surrounded by a sort of Pharisaic commission of teachers of the Law, who took care to see that this sacerdotal head should carry out the ceremonial of the day itself in accordance with Pharisaic ideas. The high priest was made to rehearse the various acts connected with day and was fully instructed in the meaning and rationale of the ceremonial as understood by Pharisees.

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

| Second Temple Herod's Temple | |

|---|---|

בֵּית־הַמִּקְדָּשׁ הַשֵּׁנִי | |

Model of Herod's Temple (inspired by the writings of Josephus) displayed within the Holyland Model of Jerusalem at the Israel Museum | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Judaism |

| Region | Land of Israel |

| Deity | Yahweh |

| Leadership | High Priest of Israel |

| Location | |

| Location | Temple Mount |

| Municipality | Jerusalem |

| State | Yehud Medinata (first) Judaea (last) |

| Country | Achaemenid Empire (first) Roman Empire (last) |

Location within the Old City of Jerusalem | |

| Geographic coordinates | 31°46′41″N 35°14′7″E |

| Architecture | |

| Founder | Zerubbabel; refurbished by Herod the Great |

| Completed | c. 516 BCE (original) c. 18 CE (Herodian) |

| Destroyed | 70 CE (Roman siege) |

| Specifications | |

| Height (max) | c. 46 metres (151 ft) |

| Materials | Jerusalem limestone |

| Excavation dates | 1930, 1967, 1968, 1970–1978, 1996–1999, 2007 |

| Archaeologists | Charles Warren, Benjamin Mazar, Ronny Reich, Eli Shukron, Yaakov Billig |

| Present-day site | Dome of the Rock |

| Public access | Limited; see Temple Mount entry restrictions |

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

The Second Temple (Hebrew: בֵּית־הַמִּקְדָּשׁ הַשֵּׁנִי Bēṯ hamMīqdāš hašŠēnī, transl. 'Second House of the Sanctum') was the reconstructed Temple in Jerusalem, in use between c. 516 BCE and its destruction in 70 CE. In its last phase it was enhanced by Herod the Great, the result being later called Herod's Temple. Defining the Second Temple period, it stood as a pivotal symbol of Jewish identity and was central to Second Temple Judaism; it was the chief place of worship, ritual sacrifice (korban), and communal gathering for Jews. As such, it attracted Jewish pilgrims from distant lands during the Three Pilgrimage Festivals: Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot.

Construction on the Second Temple began in the aftermath of the Persian conquest of Babylon; the Second Temple's predecessor, known as Solomon's Temple, had been destroyed alongside the Kingdom of Judah as a whole by the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem around 587 BCE.[1] After the Neo-Babylonian Empire was annexed by the Achaemenid Empire, the Persian king Cyrus the Great issued the so-called Edict of Cyrus, which is described in the Hebrew Bible as having authorized and encouraged the return to Zion—a biblical event in which the Jewish people returned to the former Kingdom of Judah, which the Persians had recently restructured as the self-governing Jewish province of Yehud Medinata. The completion of the Second Temple at the time of the Persian king Darius I signified a period of renewed Jewish hope and religious revival. According to biblical sources, the Second Temple was originally a relatively modest structure built under the authority of the Persian-appointed Jewish governor Zerubbabel, the grandson of Jeconiah, the penultimate king of Judah.[2]

In the 1st century BCE, the Second Temple was refurbished and expanded under the reign of Herod the Great, hence the alternative eponymous name for the structure. Herod's transformation efforts resulted in a grand and imposing structure and courtyard, including the large edifices and façades shown in modern models, such as the Holyland Model of Jerusalem in the Israel Museum. The Temple Mount, where both Solomon's Temple and the Second Temple stood, was also significantly expanded, doubling in size to become the ancient world's largest religious sanctuary.[3]

In 70 CE, at the height of the First Jewish–Roman War, the Second Temple was destroyed by the Roman siege of Jerusalem,[a] marking a cataclysmic and transformative point in Jewish history.[4] The loss of the Second Temple prompted the development of Rabbinic Judaism, which remains the mainstream form of Jewish religious practices globally.

Biblical narrative

The accession of Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid Empire in 559 BCE made the re-establishment of the city of Jerusalem and the rebuilding of the Temple possible.[5][6] Some rudimentary ritual sacrifice had continued at the site of the first temple following its destruction.[7] According to the closing verses of the second book of Chronicles and the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, when the Jewish exiles returned to Jerusalem following a decree from Cyrus the Great (Ezra 1:1–4, 2 Chronicles 36:22–23), construction started at the original site of the altar of Solomon's Temple.[1] These events represent the final section in the historical narrative of the Hebrew Bible.[5]

The original core of the book of Nehemiah, the first-person memoir, may have been combined with the core of the Book of Ezra around 400 BCE. Further editing probably continued into the Hellenistic era.[8]

Based on the biblical account, after the return from Babylonian captivity, arrangements were immediately made to reorganize the desolated Yehud Province after the demise of the Kingdom of Judah seventy years earlier. The body of pilgrims, forming a band of 42,360,[9] having completed the long and dreary journey of some four months, from the banks of the Euphrates to Jerusalem, were animated in all their proceedings by a strong religious impulse, and therefore one of their first concerns was to restore their ancient house of worship by rebuilding their destroyed Temple.[10]

On the invitation of Zerubbabel, the governor, who showed them a remarkable example of liberality by contributing personally 1,000 golden darics, besides other gifts, the people poured their gifts into the sacred treasury with great enthusiasm.[11] First they erected and dedicated the altar of God on the exact spot where it had formerly stood, and they then cleared away the charred heaps of debris that occupied the site of the old temple; and in the second month of the second year (535 BCE), amid great public excitement and rejoicing, the foundations of the Second Temple were laid. A wide interest was felt in this great movement, although it was regarded with mixed feelings by the spectators.[12][10]

The Samaritans wanted to help with this work but Zerubbabel and the elders declined such cooperation, feeling that the Jews must build the Temple unaided. Immediately evil reports were spread regarding the Jews. According to Ezra 4:5, the Samaritans sought to "frustrate their purpose" and sent messengers to Ecbatana and Susa, with the result that the work was suspended.[10]

Seven years later, Cyrus the Great, who allowed the Jews to return to their homeland and rebuild the Temple, died,[13] and was succeeded by his son Cambyses. On his death, the "false Smerdis", an impostor, occupied the throne for some seven or eight months, and then Darius became king (522 BCE). In the second year of his rule the work of rebuilding the temple was resumed and carried forward to its completion,[14] under the stimulus of the earnest counsels and admonitions of the prophets Haggai and Zechariah. It was ready for consecration in the spring of 516 BCE, more than twenty years after the return from captivity. The Temple was completed on the third day of the month Adar, in the sixth year of the reign of Darius, amid great rejoicings on the part of all the people,[2] although it was evident that the Jews were no longer an independent people, but were subject to a foreign power.

The Book of Haggai includes a prediction that the glory of the Second Temple would be greater than that of the first.[15][10] While the Temple may well have been consecrated in 516, construction and expansion may have continued as late as 500 BCE.[16]

Some of the original artifacts from the Temple of Solomon are not mentioned in the sources after its destruction in 586 BCE, and are presumed lost. The Second Temple lacked various holy articles, including the Ark of the Covenant[6][10] containing the Tablets of Stone, before which were placed the pot of manna and Aaron's rod,[10] the Urim and Thummim[6][10] (divination objects contained in the Hoshen), the holy oil[10] and the sacred fire.[6][10] The Second Temple also included many of the original vessels of gold that had been taken by the Babylonians but restored by Cyrus the Great.[10][17]

No detailed description of the Temple's architecture is given in the Hebrew Bible, save that it was sixty cubits in both width and height, and was constructed with stone and lumber.[18] In the Second Temple, the Holy of Holies (Kodesh Hakodashim) was separated by curtains rather than a wall as in the First Temple. Still, as in the Tabernacle, the Second Temple included the Menorah (golden lamp) for the Hekhal, the Table of Showbread and the golden altar of incense, with golden censers.[10]

Rabbinical literature

Traditional rabbinic literature states that the Second Temple stood for 420 years, and, based on the 2nd-century work Seder Olam Rabbah, placed construction in 356 BCE (3824 AM), 164 years later than academic estimates, and destruction in 68 CE (3828 AM).[19][b]

According to the Mishnah,[20] the "Foundation Stone" stood where the Ark used to be, and the High Priest put his censer on it on Yom Kippur.[6] The fifth order, or division, of the Mishnah, known as Kodashim, provides detailed descriptions and discussions of the religious laws connected with Temple service including the sacrifices, the Temple and its furnishings, as well as the priests who carried out the duties and ceremonies of its service. Tractates of the order deal with the sacrifices of animals, birds, and meal offerings, the laws of bringing a sacrifice, such as the sin offering and the guilt offering, and the laws of misappropriation of sacred property. In addition, the order contains a description of the Second Temple (tractate Middot), and a description and rules about the daily sacrifice service in the Temple (tractate Tamid).[21][22][23] According to the Babylonian Talmud,[24] the Temple lacked the Shekhinah (the dwelling or settling divine presence of God) and the Ruach HaKodesh (holy spirit) present in the First Temple.

Rededication by the Maccabees

Following the conquest of Judea by Alexander the Great, it became part of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt until 200 BCE, when the Seleucid king Antiochus III the Great of Syria defeated Pharaoh Ptolemy V Epiphanes at the Battle of Paneion.

In 167 BCE, Antiochus IV Epiphanes ordered an altar to Zeus erected in the Temple. He also, according to Josephus, "compelled Jews to dissolve the laws of the country, to keep their infants un-circumcised, and to sacrifice swine's flesh upon the altar; against which they all opposed themselves, and the most approved among them were put to death."[25] Following the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid empire, the Second Temple was rededicated and became the religious pillar of the Jewish Hasmonean Kingdom, as well as culturally associated with the Jewish holiday of Hanukkah.[26][27]

Hasmonean dynasty and Roman conquest

There is some evidence from archaeology that further changes to the structure of the Temple and its surroundings were made during the Hasmonean rule. Salome Alexandra, the queen of the Hasmonean Kingdom appointed her elder son Hyrcanus II as the high priest of Judaea. Her younger son Aristobulus II was determined to have the throne, and as soon as she died he seized the throne. Hyrcanus, who was next in the succession, agreed to be content with being high priest. Antipater, the governor of Idumæa, encouraged Hyrcanus not to give up his throne. Eventually, Hyrcanus fled to Aretas III, king of the Nabateans, and returned with an army to take back the throne. He defeated Aristobulus and besieged Jerusalem. The Roman general Pompey, who was in Syria fighting against the Armenians in the Third Mithridatic War, sent his lieutenant to investigate the conflict in Judaea. Both Hyrcanus and Aristobulus appealed to him for support. Pompey was not diligent in making a decision about this, which caused Aristobulus to march off. He was pursued by Pompey and surrendered but his followers closed Jerusalem to Pompey's forces. The Romans besieged and took the city in 63 BCE. The priests continued with the religious practices inside the Temple during the siege. The temple was not looted or harmed by the Romans. Pompey himself, perhaps inadvertently, went into the Holy of Holies and the next day ordered the priests to repurify the Temple and resume the religious practices.[28]

Herod's Temple

The writings of Flavius Josephus and the information in tractate Middot of the Mishnah had for long been used for proposing possible designs for the Temple up to 70 CE.[1] The discovery of the Temple Scroll as part of the Dead Sea Scrolls in the 20th century provided another possible source. Lawrence Schiffman states that after studying Josephus and the Temple Scroll, he found Josephus to be historically more reliable than the Temple Scroll.[29]

Temenos expansion, date and duration

Reconstruction of the temple under Herod began with a massive expansion of the Temple Mount temenos. For example, the Temple Mount complex initially measured 7 hectares (17 acres) in size, but Herod expanded it to 14.4 hectares (36 acres) and so doubled its area.[30] Herod's work on the Temple is generally dated from 20/19 BCE until 12/11 or 10 BCE. Writer Bieke Mahieu dates the work on the Temple enclosures from 25 BCE and that on the Temple building in 19 BCE, and situates the dedication of both in November 18 BCE.[31]

Religious worship and temple rituals continued during the construction process.[32]

Extent and financing

The old temple built by Zerubbabel was replaced by a magnificent edifice. Herod's Temple was one of the larger construction projects of the 1st century BCE.[33] Josephus records that Herod was interested in perpetuating his name through building projects, that his construction programs were extensive and paid for by heavy taxes, but that his masterpiece was the Temple of Jerusalem.[33]

Later, the sanctuary shekel was reinstituted to support the temple as the temple tax.[34]

Elements

Platform, substructures, retaining walls

Mt. Moriah had a plateau at the northern end, and steeply declined on the southern slope. It was Herod's plan that the entire mountain be turned into a giant square platform. The Temple Mount was originally intended[by whom?] to be 1,600 feet (490 m) wide by 900 feet (270 m) broad by 9 stories high, with walls up to 16 feet (4.9 m) thick, but had never been finished. To complete it, a trench was dug around the mountain, and huge stone blocks were laid. Some of these weighed well over 100 tons, the largest measuring 44.6 by 11 by 16.5 feet (13.6 m × 3.4 m × 5.0 m) and weighing approximately 567–628 tons.[35][unreliable source?]

Court of the Gentiles

The Court of the Gentiles was primarily a bazaar, with vendors selling souvenirs, sacrificial animals, food. Currency was also exchanged, with Roman currency exchanged for Tyrian money, as also mentioned in the New Testament account of Jesus and the Money Changers, when Jerusalem was packed with Jewish pilgrims who had come for Passover, perhaps numbering 300,000 to 400,000.[36][37]

Above the Huldah Gates, on top the Temple walls, was the Royal Stoa, a large basilica praised by Josephus as "more worthy of mention than any other [structure] under the sun"; its main part was a lengthy Hall of Columns which includes 162 columns, structured in four rows.[38]

The Royal Stoa is widely accepted to be part of Herod's work; however, recent archaeological finds in the Western Wall tunnels suggest that it was built in the first century during the reign of Agripas, as opposed to the 1st century BCE.[39]

Pinnacle

The accounts of the temptation of Christ in the gospels of Matthew and Luke both suggest that the Second Temple had one or more 'pinnacles':

The Greek word used is πτερύγιον (pterugion), which literally means a tower, rampart, or pinnacle.[41] According to Strong's Concordance, it can mean little wing, or by extension anything like a wing such as a battlement or parapet.[42] The archaeologist Benjamin Mazar thought it referred to the southeast corner of the Temple overlooking the Kidron Valley.[43]

Inner courts

According to Josephus, there were ten entrances into the inner courts, four on the south, four on the north, one on the east and one leading east to west from the Court of Women to the court of the Israelites, named the Nicanor Gate.[44] According to Josephus, Herod the Great erected a golden eagle over the great gate of the Temple.[45]

Roofs

Joachim Bouflet states that "the teams of archaeologists Nahman Avigad in 1969–1980 in the Herodian city of Jerusalem, and Yigael Shiloh in 1978–1982, in the city of David" have proven that the roofs of the Second Temple had no dome. In this, they support Josephus' description of the Second Temple.[46]

Pilgrimages

Jews from distant parts of the Roman Empire would arrive by boat at the port of Jaffa,[citation needed] where they would join a caravan for the three-day trek to the Holy City and would then find lodgings in one of the many hotels or hostelries. Then they changed some of their money from the profane standard Greek and Roman currency for Jewish and Tyrian money, the latter two considered religious.[47][48]

Destruction

In 66 CE, the Jewish population rebelled against the Roman Empire. Four years later, on the Hebrew calendrical date of Tisha B'Av, either 4 August 70[49] or 30 August 70,[50] Roman legions under Titus retook and destroyed much of Jerusalem and Herod's Temple. Josephus, while an apologist for the Empire, claims the burning of the Temple was the impulsive act of a Roman soldier, despite Titus's orders to preserve it, whereas later Christian sources, traced to Tacitus, suggest that Titus himself authorized the destruction, a view currently favored by modern scholars, though the debate persists.[51]

The Arch of Titus, which was built in Rome to commemorate Titus's victory in Judea, depicts a Roman triumph, with soldiers carrying spoils from the Temple, including the temple menorah. According to an inscription on the Colosseum, Emperor Vespasian built the Colosseum with war spoils in 79–possibly from the spoils of the Second Temple.[52] The sects of Judaism that had their base in the Temple dwindled in importance, including the priesthood and the Sadducees.[53]

The Temple was on the site of what today is the Dome of the Rock. The gates led close to what is now al-Aqsa Mosque, built much later.[32] Although Jews continued to inhabit the destroyed city, Emperor Hadrian established a new Roman colonia called Aelia Capitolina. At the end of the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135 CE, many of the Jewish communities were massacred. Jews were banned from entering Jerusalem.[28] A Roman temple was set up on the former site of Herod's Temple for the practice of Roman religion.

Historical accounts relate that not only the Jewish Temple was destroyed, but also the entire Lower city of Jerusalem.[54] Even so, according to Josephus, Titus did not totally raze the towers (such as the Tower of Phasael, now erroneously called the Tower of David), keeping them as a memorial of the city's strength.[55][56] The Midrash Rabba (Eikha Rabba 1:32) recounts a similar episode related to the destruction of the city, according to which Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai, during the Roman siege of Jerusalem, requested of Vespasian that he spare the westernmost gates of the city (Hebrew: פילי מערבאה) that lead to Lydda (Lod). When the city was eventually taken, the Arab auxiliaries who had fought alongside the Romans under their general, Fanjar, also spared that westernmost wall from destruction.[57]

Jewish eschatology includes a belief that the Second Temple will be replaced by a future Third Temple in Jerusalem.[58]

Archaeology of the Temple

Temple warning inscriptions

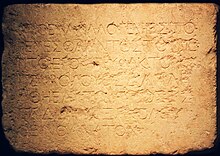

In 1871, a hewn stone measuring 60 cm × 90 cm (24 in × 35 in) and engraved with Greek uncials was discovered near a court on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem and identified by Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau as being the Temple Warning inscription. The stone inscription outlined the prohibition extended to those who were not of the Jewish nation to proceed beyond the soreg separating the larger Court of the Gentiles and the inner courts. The inscription read in seven lines:

Today, the stone is preserved in Istanbul's Museum of Antiquities.[59]

In 1935 a fragment of another similar Temple warning inscription was found.[59]

The word "foreigner" has an ambiguous meaning. Some scholars believe it referred to all gentiles, regardless of ritual purity status or religion. Others argue that it referred to unconverted Gentiles since Herod wrote the inscription. Herod himself was a converted Idumean (or Edomite) and was unlikely to exclude himself or his descendants.[60]

Place of trumpeting

Another ancient inscription, partially preserved on a stone discovered below the southwest corner of the Herodian Mount, contains the words "to the place of trumpeting". The stone's shape suggests that it was part of a parapet, and it has been interpreted as belonging to a spot on the Mount described by Josephus, "where one of the priests to stand and to give notice, by sound of trumpet, in the afternoon of the approach, and on the following evening of the close, of every seventh day" closely resembling what the Talmud says.[61]

Walls and gates of the Temple complex

After 1967, archaeologists found that the wall extended all the way around the Temple Mount and is part of the city wall near the Lions' Gate. Thus, the remaining part of the Temple Mount is not only the Western Wall. Currently, Robinson's Arch (named after American Edward Robinson) remains as the beginning of an arch that spanned the gap between the top of the platform and the higher ground farther away. Visitors and pilgrims also entered through the still-extant, but now plugged, gates on the southern side that led through colonnades to the top of the platform. The Southern wall was designed as a grand entrance.[62] Recent archaeological digs have found numerous mikvehs (ritual baths) for the ritual purification of the worshipers, and a grand stairway leading to one of the now blocked entrances.[62]

Underground structures

Inside the walls, the platform was supported by a series of vaulted archways, now called Solomon's Stables, which still exist. Their current renovation by the Waqf is extremely controversial.[63]

Quarry

On September 25, 2007, Yuval Baruch, archaeologist with the Israeli Antiquities Authority announced the discovery of a quarry compound that may have provided King Herod with the stones to build his Temple on the Temple Mount. Coins, pottery and an iron stake found proved the date of the quarrying to be about 19 BCE.[how?] Archaeologist Ehud Netzer confirmed that the large outlines of the stone cuts is evidence that it was a massive public project worked by hundreds of slaves.[64]

Floor tiling from courts

More recent findings from the Temple Mount Sifting Project include floor tiling from the Second Temple period.[65]

Magdala stone interpretation

The Magdala stone is thought to be a representation of the Second Temple carved before its destruction in the year 70.[66]

Second Temple Judaism

The period between the construction of the Second Temple in 515 BCE and its destruction by the Romans in 70 CE witnessed major historical upheavals and significant religious changes that would affect most subsequent Abrahamic religions. The origins of the authority of scripture, of the centrality of law and morality in religion, of the synagogue and of apocalyptic expectations for the future all developed in the Judaism of this period.

See also

- Archaeological remnants of the Jerusalem Temple

- Herodian architecture

- Jerusalem stone

- List of artifacts significant to the Bible

- List of megalithic sites

- Replicas of the Jewish Temple

- Temple of Peace, Rome

- Temple in Jerusalem

- Timeline of Jewish history

Notes

- ^ Based on regnal years of Darius I, brought down in Richard Parker & Waldo Dubberstein's Babylonian Chronology, 626 B.C.–A.D. 75, Brown University Press: Providence 1956, p. 30. However, Jewish tradition holds that the Second Temple stood for only 420 years, i.e. from 352 BCE – 68 CE. See: Hadad, David (2005). Sefer Maʻaśe avot (in Hebrew) (4 ed.). Beer Sheba: Kodesh Books. p. 364. OCLC 74311775. (with endorsements by Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, Rabbi Shlomo Amar, and Rabbi Yona Metzger); Sar-Shalom, Rahamim (1984). She'harim La'Luah Ha'ivry (Gates to the Hebrew Calendar) (in Hebrew). Tel-Aviv. p. 161 (Comparative chronological dates). OCLC 854906532.; Maimonides (1974). Sefer Mishneh Torah - HaYad Ha-Chazakah (Maimonides' Code of Jewish Law) (in Hebrew). Vol. 4. Jerusalem: Pe'er HaTorah. pp. 184–185 [92b–93a] (Hil. Shmitta ve-yovel 10:2–4). OCLC 122758200.

According to this calculation, this year which is one-thousand, one-hundred and seven years following the destruction, which year in the Seleucid era counting is [today] the 1,487th year (corresponding with Tishri 1175–Elul 1176 CE), being the year 4,936 anno mundi, it is a Seventh Year [of the seven-year cycle], and it is the 21st year of the Jubilee" (END QUOTE). = the destruction occurring in the lunar month of Av, two months preceding the New Year of 3,829 anno mundi.

- ^ Classical Jewish records (e.g. Maimonides' Responsa, etc.) put the Second Temple period from 352 BCE to 68 CE, a total of 420 years.

References

- ^ a b c Schiffman, Lawrence H. (2003). Understanding Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism. New York: KTAV Publishing House. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-88125-813-4. Archived from the original on 2023-08-30. Retrieved 2019-08-19.

- ^ a b Ezra 6:15,16

- ^ Feissel, Denis (23 December 2010). Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae: Volume 1 1/1: Jerusalem, Part 1: 1-704. Hannah M. Cotton, Werner Eck, Marfa Heimbach, Benjamin Isaac, Alla Kushnir-Stein, Haggai Misgav. Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-11-174100-0. OCLC 840438627.

- ^ Karesh, Sara E. (2006). Encyclopedia of Judaism. Facts On File. ISBN 978-1-78785-171-9. OCLC 1162305378.

Until the modern period, the destruction of the Temple was the most cataclysmic moment in the history of the Jewish people. [...] The sage Yochanan ben Zakkai, with permission from Rome, set up the outpost of Yavneh to continue develop of Pharisaic, or rabbinic, Judaism.

- ^ a b Albright, William (1963). The Biblical Period from Abraham to Ezra: An Historical Survey. HarperCollins College Division. ISBN 978-0-06-130102-5.

- ^ a b c d e

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Temple, The Second". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Temple, The Second". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. - ^ Zevit, Ziony (2008). "From Judaism to Biblical Religion and Back Again". The Hebrew Bible: New Insights and Scholarship. New York University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-8147-3187-1. Archived from the original on 2023-08-30. Retrieved 2022-10-17.

- ^ Cartledge, Paul; Garnsey, Peter; Gruen, Erich S., eds. (1997). Hellenistic Constructs: Essays In Culture, History, and Historiography. California: University of California Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-520-20676-2.

- ^ Ezra 2:65

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Easton, Matthew George (1897). . Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

- ^ Ezra 2

- ^ Haggai 2:3, Zechariah 4:10

- ^ 2 Chronicles 36:22–23

- ^ Ezra 5:6–6:15

- ^ Haggai 2:9

- ^ Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period: Yehud: A History of the Persian Province of Judah. Library of Second Temple Studies 47. Vol. 1. T&T Clark. pp. 282–285. ISBN 978-0-567-08998-4.

- ^ Ezra 1:7–11

- ^ Ezra 6:3–4

- ^ Seder Olam Rabbah chapter 30; Tosefta (Zevahim 13:6); Jerusalem Talmud (Megillah 18a); Babylonian Talmud (Megillah 11b–12a; Arakhin 12b; Baba Bathra 4a), Maimonides, Mishneh Torah (Hil. Shmita ve-yovel 10:3). Cf. Goldwurm, Hersh. History of the Jewish people: the Second Temple era Archived 2023-08-30 at the Wayback Machine, Mesorah Publications, 1982. Appendix: Year of the Destruction, p. 213. ISBN 978-0-89906-454-3

- ^ Middot 3:6

- ^ Birnbaum, Philip (1975). "Kodashim". A Book of Jewish Concepts. New York: Hebrew Publishing Company. pp. 541–542. ISBN 978-0-88482-876-1.

- ^ Epstein, Isidore, ed. (1948). "Introduction to Seder Kodashim". The Babylonian Talmud. Vol. 5. Singer, M. H. (translator). London: The Soncino Press. pp. xvii–xxi.

- ^ Arzi, Abraham (1978). "Kodashim". Encyclopedia Judaica. Vol. 10 (1st ed.). Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House Ltd. pp. 1126–1127.

- ^ "Yoma 21b:7". www.sefaria.org. Archived from the original on 2022-01-07. Retrieved 2019-08-05.

- ^ Josephus, Flavius (2012-06-29). "The Wars of the Jews". p. i. 34. Archived from the original on 2012-06-29. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kaufmann, Kohler (1901–1906). "Ḥanukkah". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kaufmann, Kohler (1901–1906). "Ḥanukkah". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. - ^ Goldman, Ari L. (2000). Being Jewish: The Spiritual and Cultural Practice of Judaism Today. Simon & Schuster. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-684-82389-8.

- ^ a b Lester L. Grabbe (2010). An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel, and Jesus. A&C Black. pp. 19–20, 26–29. ISBN 978-0-567-55248-8. Archived from the original on 2023-08-30. Retrieved 2015-04-03.

- ^ Lawrence Schiffman "Descriptions of the Jerusalem Temple in Josephus and the Temple Scroll" in Chapter 11 of "The Courtyards of the House of the Lord", Brill, 2008 ISBN 978-90-04-12255-0

- ^ Petrech & Edelcopp, "Four stages in the evolution of the Temple Mount", Revue Biblique (2013), pp. 343–344

- ^ Mahieu, B., Between Rome and Jerusalem, OLA 208, Leuven: Peeters, 2012, pp. 147–165

- ^ a b Leen and Kathleen Ritmeyer (1998). Secrets of Jerusalem's Temple Mount.

- ^ a b Flavius Josephus: The Jewish War

- ^ Exodus 30:13

- ^ Dan Bahat: Touching the Stones of our Heritage, Israeli ministry of Religious Affairs, 2002

- ^ Sanders, E. P. The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin, 1993. p. 249

- ^ Funk, Robert W. and the Jesus Seminar. The Acts of Jesus: The Search for the Authentic Deeds of Jesus. HarperSanFrancisco. 1998.

- ^ Mazar, Benjamin (1979). "The Royal Stoa in the Southern Part of the Temple Mount". Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research. 46/47: 381–387. doi:10.2307/3622363. ISSN 0065-6798. JSTOR 3622363.

- ^ "Israel Antiquities Authority". Archived from the original on 2021-03-05. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ^ Luke 4:9

- ^ Kittel, Gerhard, ed. (1976) [1965]. Theological Dictionary of the New Testament: Volume III. Translated by Bromiley, Geoffrey W. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans. p. 236.

- ^ Strong's Concordance 4419

- ^ Mazar, Benjamin (1975). The Mountain of the Lord, Doubleday. p. 149.

- ^ Josephus, War 5.5.2; 198; m. Mid. 1.4

- ^ Josephus, War 1.648–655; Ant 17.149–63. On this, see inter alia: Albert Baumgarten, 'Herod's Eagle', in Aren M. Maeir, Jodi Magness and Lawrence H. Schiffman (eds), 'Go Out and Study the Land' (Judges 18:2): Archaeological, Historical and Textual Studies in Honor of Hanan Eshel (JSJ Suppl. 148; Leiden: Brill, 2012), pp. 7–21; Jonathan Bourgel, "Herod's golden eagle on the Temple gate: a reconsideration Archived 2023-08-30 at the Wayback Machine," Journal of Jewish Studies 72 (2021), pp. 23–44.

- ^ Bouflet, Joachim (2023). "Fraudes Mystiques Récentes – Maria Valtorta (1897–1961) – Anachronismes et incongruités". Impostures mystiques [Mystical Frauds] (in French). Éditions du Cerf. ISBN 978-2-204-15520-5.

- ^ Sanders, E. P. The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin, 1993.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. Jesus, Interrupted, HarperCollins, 2009. ISBN 978-0-06-117393-6

- ^ "Hebrew Calendar". www.cgsf.org. Archived from the original on 2018-12-24. Retrieved 2018-11-14.

- ^ Bunson, Matthew (1995). A Dictionary of the Roman Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-19-510233-8. Archived from the original on 2023-08-30. Retrieved 2022-02-11.

- ^ Goldenberg, Robert (2006), Katz, Steven T. (ed.), "The destruction of the Jerusalem Temple: its meaning and its consequences", The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 4: The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, The Cambridge History of Judaism, vol. 4, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 194–195, doi:10.1017/chol9780521772488.009, ISBN 978-0-521-77248-8, retrieved 2024-09-16

- ^ Bruce Johnston (15 June 2001). "Colosseum 'built with loot from sack of Jerusalem temple'". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2022-01-11.

- ^ Alföldy, Géza (1995). "Eine Bauinschrift aus dem Colosseum". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik. 109: 195–226. JSTOR 20189648.

- ^ Josephus (The Jewish War 6.6.3. Archived 2023-08-30 at the Wayback Machine). Quote: "...So he (Titus) gave orders to the soldiers both to burn and plunder the city; who did nothing indeed that day; but on the next day they set fire to the repository of the archives, to Acra, to the council-house, and to the place called Ophlas; at which time the fire proceeded as far as the palace of queen Helena, which was in the middle of Acra: the lanes also were burnt down, as were also those houses that were full of the dead bodies of such as were destroyed by famine."

- ^ Josephus (The Jewish War 7.1.1.), Quote: "Caesar gave orders that they should now demolish the entire city and temple, but should leave as many of the towers standing as were of the greatest eminence; that is, Phasael, and Hippicus, and Mariamme, and so much of the wall as enclosed the city on the west side. This wall was spared, in order to afford a camp for such as were to lie in garrison; as were the towers also spared, in order to demonstrate to posterity what kind of city it was, and how well fortified, which the Roman valour had subdued."

- ^ Ben Shahar, Meir (2015). "When was the Second Temple Destroyed? Chronology and Ideology in Josephus and in Rabbinic Literature". Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Period. 46 (4/5). Brill: 562. doi:10.1163/15700631-12340439. JSTOR 24667712.

- ^ Midrash Rabba (Eikha Rabba 1:32)

- ^ "A Christian view of the coming Temple – opinion". The Jerusalem Post – Christian World. Archived from the original on 2022-08-07. Retrieved 2022-07-24.

- ^ a b Zion, Ilan Ben. "Ancient Temple Mount 'warning' stone is 'closest thing we have to the Temple'". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 2023-08-30. Retrieved 2022-10-16.

- ^ Thiessen, Matthew (2011). Contesting Conversion: Genealogy, Circumcision, and Identity in Ancient Judaism and Christianity. Oxford University Press. pp. 87–110. ISBN 9780199914456.

- ^ "'To the place of trumpeting …,' Hebrew inscription on a parapet from the Temple Mount". Jerusalem: The Israel Museum. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ a b Mazar, Eilat (2002). The Complete Guide to the Temple Mount Excavations. Jerusalem: Shoham Academic Research and Publication. pp. 55–57. ISBN 978-965-90299-1-4.

- ^ "Debris removed from Temple Mount sparks controversy". The Jerusalem Post | Jpost.com. Archived from the original on 2022-10-04. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- ^ Gaffney, Sean (2007-09-24). "Herod's Temple quarry found". USA Today.com. Archived from the original on 2010-08-09. Retrieved 2013-08-31.

- ^ "Second Temple Flooring restored". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 16 May 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ^ Kershner, Isabel (8 December 2015). "A Carved Stone Block Upends Assumptions About Ancient Judaism". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

Further reading

- Grabbe, Lester. 2008. A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period. 2 vols. New York: T&T Clark.

- Nickelsburg, George. 2005. Jewish Literature between the Bible and the Mishnah: A Historical and Literary Introduction. 2nd ed. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress.

- Schiffman, Lawrence, ed. 1998. Texts and Traditions: A Source Reader for the Study of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism. Hoboken, New Jersey: KTAV.

- Stone, Michael, ed. 1984. The Literature of the Jewish People in the Period of the Second Temple and the Talmud. 2 vols. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Fortress.

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

The Mishnah or the Mishna (/ˈmɪʃnə/; Hebrew: מִשְׁנָה, "study by repetition", from the verb shanah שנה, or "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first written collection of the Jewish oral traditions that are known as the Oral Torah. It is also the first work of rabbinic literature, with the oldest surviving material dating to the 6th to 7th centuries BCE.[1][2][3]

The Mishnah was redacted by Judah ha-Nasi probably in Beit Shearim or Sepphoris[4] between the ending of the second century CE and the beginning of the third century[5][6] in a time when the persecution of Jews and the passage of time raised the possibility that the details of the oral traditions of the Pharisees from the Second Temple period (516 BCE – 70 CE) would be forgotten.

Most of the Mishnah is written in Mishnaic Hebrew, but some parts are in Jewish Western Aramaic.

Six orders

[edit]The term "Mishnah" originally referred to a method of teaching by presenting topics in a systematic order, as contrasted with Midrash, which followed the order of the Bible. As a written compilation, the order of the Mishnah is by subject matter and includes a much broader selection of halakhic subjects and discusses individual subjects more thoroughly than the Midrash.

The Mishnah consists of six orders (sedarim, singular seder סדר), each containing 7–12 tractates (masechtot, singular masechet מסכת; lit. "web"), 63 in total. Each masechet is divided into chapters (peraqim, singular pereq) and then paragraphs (mishnayot, singular mishnah). In this last context, the word mishnah means a single paragraph of the work, i.e. the smallest unit of structure, leading to the use of the plural, "Mishnayot", for the whole work.

Because of the division into six orders, the Mishnah is sometimes called Shas (an acronym for Shisha Sedarim – the "six orders"), although that term is more often used for the Talmud as a whole.

The six orders are:

- Zeraim ("Seeds"), dealing with prayer and blessings, tithes and agricultural laws (11 tractates)

- Moed ("Festival"), pertaining to the laws of the Sabbath and the Festivals (12 tractates)

- Nashim ("Women"), concerning marriage and divorce, some forms of oaths and the laws of the nazirite (7 tractates)

- Nezikin ("Damages"), dealing with civil and criminal law, the functioning of the courts and oaths (10 tractates)

- Kodashim ("Holy things"), regarding sacrificial rites, the Temple, and the dietary laws (11 tractates) and

- Tohorot ("Purities"), pertaining to the laws of purity and impurity, including the impurity of the dead, food purity, and bodily purity (12 tractates).

The acronym "Z'MaN NaKaT" is a popular mnemonic for these orders.[7] In each order (with the exception of Zeraim), tractates are arranged from biggest (in number of chapters) to smallest.

The Babylonian Talmud (Hagiga 14a) states that there were either six hundred or seven hundred orders of the Mishnah. The Mishnah was divided into six thematic sections by its author, Judah HaNasi.[8][9] There is also a tradition that Ezra the scribe dictated from memory not only the 24 books of the Tanakh but 60 esoteric books. It is not known whether this is a reference to the Mishnah, but there is a case for saying that the Mishnah does consist of 60 tractates. (The current total is 63, but Makkot was originally part of Sanhedrin, and Bava Kamma (literally: "First Portal"), Bava Metzia ("Middle Portal") and Bava Batra ("Final Portal") are often regarded as subdivisions of one enormous tractate, titled simply Nezikin.)

Omissions

[edit]A number of important laws are not elaborated upon in the Mishnah. These include the laws of tzitzit, tefillin (phylacteries), mezuzot, the holiday of Hanukkah, and the laws of conversion to Judaism. These were later discussed in the minor tractates.

Nissim ben Jacob's Hakdamah Le'mafteach Hatalmud argued that it was unnecessary for "Judah the Prince" to discuss them as many of these laws were so well known. Margolies suggests that as the Mishnah was redacted after the Bar Kokhba revolt, Judah could not have included discussion of Hanukkah, which commemorates the Jewish revolt against the Seleucid Empire (the Romans would not have tolerated this overt nationalism). Similarly, there were then several decrees in place aimed at suppressing outward signs of national identity, including decrees against wearing tefillin and tzitzit; as conversion to Judaism was against Roman law, Judah would not have discussed this.[10]

David Zvi Hoffmann suggests that there existed ancient texts analogous to the present-day Shulchan Aruch that discussed the basic laws of day to day living and it was therefore not necessary to focus on these laws in the Mishnah.

Mishnah, Gemara, and Talmud

[edit]Rabbinic commentary, debate and analysis on the Mishnah from the next four centuries, done in the Land of Israel and in Babylonia, were eventually redacted and compiled as well. In themselves they are known as Gemara. The books which set out the Mishnah in its original structure, together with the associated Gemara, are known as Talmuds. Two Talmuds were compiled, the Babylonian Talmud (to which the term "Talmud" normally refers) and the Jerusalem Talmud, with the oldest surviving Talmudic manuscripts dating to the 8th century CE.[2][3] Unlike the Hebrew Mishnah, the Gemara is written primarily in Aramaic.

Content and purpose

[edit]

The Mishnah teaches the oral traditions by example, presenting actual cases being brought to judgment, usually along with (i) the debate on the matter, and (ii) the judgment that was given by a notable rabbi based on halakha, mitzvot, and spirit of the teaching ("Torah") that guided his decision.

In this way, the Mishnah brings to everyday reality the practice of the 613 Commandments presented in the Torah and aims to cover all aspects of human living, serve as an example for future judgments, and, most important, demonstrate pragmatic exercise of the Biblical laws, which was much needed since the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. The Mishnah is thus a collection of existing traditions rather than new law.[11]

The term "Mishnah" is related to the verb "to teach, repeat", and to adjectives meaning "second". It is thus named for being both the one written authority (codex) secondary (only) to the Tanakh as a basis for the passing of judgment, a source and a tool for creating laws, and the first of many books to complement the Tanakh in certain aspects.

Oral law

[edit]Before the publication of the Mishnah, Jewish scholarship and judgement were predominantly oral, as according to the Talmud, it was not permitted to write them down.[12] The earliest recorded oral law may have been of the midrashic form, in which halakhic discussion is structured as exegetical commentary on the Torah, with the oldest surviving material dating to the 6th to 7th centuries CE.[2][3][13] Rabbis expounded on and debated the Tanakh without the benefit of written works (other than the Biblical books themselves), though some may have made private notes (מגילות סתרים) for example of court decisions. The oral traditions were far from monolithic, and varied among various schools, the most famous of which were the House of Shammai and the House of Hillel.

After the First Jewish–Roman War in 70 CE, with the end of the Second Temple Jewish center in Jerusalem, Jewish social and legal norms were in upheaval. The Rabbis were faced with the new reality of Judaism without a Temple (to serve as the center of teaching and study) and Judea without autonomy. It is during this period that Rabbinic discourse began to be recorded in writing.[14][15] The possibility was felt that the details of the oral traditions of the Pharisees from the Second Temple period (530s BCE / 3230s AM – 70 CE/ 3830 AM) would be forgotten, so the justification was found to have these oral laws transcribed.[16][17]

Over time, different traditions of the Oral Law came into being, raising problems of interpretation. According to the Mevo Hatalmud,[18] many rulings were given in a specific context but would be taken out of it, or a ruling was revisited, but the second ruling would not become popularly known. To correct this, Judah the Prince took up the redaction of the Mishnah. If a point was of no conflict, he kept its language; where there was conflict, he reordered the opinions and ruled, and he clarified where context was not given. The idea was not to use his discretion, but rather to examine the tradition as far back as he could, and only supplement as required.[19]

The Mishnah and the Hebrew Bible

[edit]According to Rabbinic Judaism, the Oral Torah (Hebrew: תורה שבעל-פה) was given to Moses with the Torah at Mount Sinai or Mount Horeb as an exposition to the latter. The accumulated traditions of the Oral Law, expounded by scholars in each generation from Moses onward, is considered as the necessary basis for the interpretation, and often for the reading, of the Written Law. Jews sometimes refer to this as the Masorah (Hebrew: מסורה), roughly translated as tradition, though that word is often used in a narrower sense to mean traditions concerning the editing and reading of the Biblical text (see Masoretic Text). The resulting Jewish law and custom is called halakha.

While most discussions in the Mishnah concern the correct way to carry out laws recorded in the Torah, it usually presents its conclusions without explicitly linking them to any scriptural passage, though scriptural quotations do occur. For this reason it is arranged in order of topics rather than in the form of a Biblical commentary. (In a very few cases, there is no scriptural source at all and the law is described as Halakha leMoshe miSinai, "law to Moses from Sinai".) The Midrash halakha, by contrast, while presenting similar laws, does so in the form of a Biblical commentary and explicitly links its conclusions to details in the Biblical text. These Midrashim often predate the Mishnah.

The Mishnah also quotes the Torah for principles not associated with law, but just as practical advice, even at times for humor or as guidance for understanding historical debates.

Rejection

[edit]Some Jews do not accept the codification of the oral law at all. Karaite Judaism, for example, recognises only the Tanakh as authoritative in Halakha (Jewish religious law) and theology. It rejects the codification of the Oral Torah in the Mishnah and Talmud and subsequent works of mainstream Rabbinic Judaism which maintain that the Talmud is an authoritative interpretation of the Torah. Karaites maintain that all of the divine commandments handed down to Moses by God were recorded in the written Torah without additional Oral Law or explanation. As a result, Karaite Jews do not accept as binding the written collections of the oral tradition in the Midrash or Talmud. The Karaites comprised a significant portion of the world Jewish population in the 10th and 11th centuries CE, and remain extant, although they currently number in the thousands.

Authorship

[edit]The rabbis who contributed to the Mishnah are known as the Tannaim,[20][21] of whom approximately 120 are known. The period during which the Mishnah was assembled spanned about 130 years, or five generations, in the first and second centuries CE. Judah ha-Nasi is credited with the final redaction and publication of the Mishnah,[22] although there have been a few additions since his time:[23] those passages that cite him or his grandson (Judah II), and the end of tractate Sotah (which refers to the period after Judah's death). In addition to redacting the Mishnah, Judah and his court also ruled on which opinions should be followed, although the rulings do not always appear in the text.

Most of the Mishnah is related without attribution (stam). This usually indicates that many sages taught so, or that Judah the Prince ruled so. The halakhic ruling usually follows that view. Sometimes, however, it appears to be the opinion of a single sage, and the view of the sages collectively (Hebrew: חכמים, hachamim) is given separately.

As Judah the Prince went through the tractates, the Mishnah was set forth, but throughout his life some parts were updated as new information came to light. Because of the proliferation of earlier versions, it was deemed too hard to retract anything already released, and therefore a second version of certain laws were released. The Talmud refers to these differing versions as Mishnah Rishonah ("First Mishnah") and Mishnah Acharonah ("Last Mishnah"). David Zvi Hoffmann suggests that Mishnah Rishonah actually refers to texts from earlier Sages upon which Rebbi based his Mishnah.

The Talmud records a tradition that unattributed statements of the law represent the views of Rabbi Meir (Sanhedrin 86a), which supports the theory (recorded by Sherira Gaon in his famous Iggeret) that he was the author of an earlier collection. For this reason, the few passages that actually say "this is the view of Rabbi Meir" represent cases where the author intended to present Rabbi Meir's view as a "minority opinion" not representing the accepted law.

There are also references to the "Mishnah of Rabbi Akiva", suggesting a still earlier collection;[24] on the other hand, these references may simply mean his teachings in general. Another possibility is that Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Meir established the divisions and order of subjects in the Mishnah, making them the authors of a school curriculum rather than of a book.

Authorities are divided on whether Rabbi Judah the Prince recorded the Mishnah in writing or established it as an oral text for memorisation. The most important early account of its composition, the Iggeret Rav Sherira Gaon (Epistle of Rabbi Sherira Gaon) is ambiguous on the point, although the Spanish recension leans to the theory that the Mishnah was written. However, the Talmud records that, in every study session, there was a person called the tanna appointed to recite the Mishnah passage under discussion. This may indicate that, even if the Mishnah was reduced to writing, it was not available on general distribution.

Mishnah studies

[edit]Textual variants

[edit]Very roughly, there are two traditions of Mishnah text. One is found in manuscripts and printed editions of the Mishnah on its own, or as part of the Jerusalem Talmud. The other is found in manuscripts and editions of the Babylonian Talmud; though there is sometimes a difference between the text of a whole paragraph printed at the beginning of a discussion (which may be edited to conform with the text of the Mishnah-only editions) and the line-by-line citations in the course of the discussion.

Robert Brody, in his Mishna and Tosefta Studies (Jerusalem 2014), warns against over-simplifying the picture by assuming that the Mishnah-only tradition is always the more authentic, or that it represents a "Palestinian" as against a "Babylonian" tradition. Manuscripts from the Cairo Geniza, or citations in other works, may support either type of reading or other readings altogether.

Manuscripts

[edit]Complete manuscripts (mss.) bolded. The earliest extant material witness to rabbinic literature of any kind is dating to the 6th–7th centuries CE, see Mosaic of Rehob.[2][3]

| Usual name | Formal designation | Place written | Period written | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaufmann | Hungarian Academy of Sciences Library Kaufmann ms. A50 | Prob. Palestine | 10th, possibly 11th C. | It is considered the best manuscript and forms the base text of all critical editions. Vocalization is by a different, later hand. |

| Parma | Biblioteca Palatina ms. Parm. 3173 | Palestine or Southern Italy, which in any case it reached soon after being written down | Script shows strong similarities to Codex Hebr. Vaticanus 31, securely dated to 1073 | The Parma ms. is close to the Kaufmann ms. palaeographically but not textually. Text is closest to the Mishnah quotations given in the Leiden Palestinian Talmud. |

| Cambridge / Lowe | Cambridge University Library ms. Add. 470 (II) | Sepharadic | 14–15th C. | A very careless copy, it is nonetheless useful where the Kaufmann text is corrupt. |

| Parma B | North Africa | 12–13th C. | Toharot only. Unlike all of the above mss., the vocalization and consonant text are probably by the same hand, which makes it the oldest vocalization of part of the Mishnah known. | |

| Yemenite ms. | National Library of Israel quarto 1336 | Yemen | 17–18th C. | Nezikin to Toharot. The consonant text is dependent on early printed editions. The value of this ms. lies exclusively in the vocalization. |

The Literature of the Jewish People in the Period of the Second Temple and the Talmud, Volume 3 The Literature of the Sages: First Part: Oral Tora, Halakha, Mishna, Tosefta, Talmud, External Tractates. Compendia Rerum Iudaicarum ad Novum Testamentum, Ed. Shmuel Safrai, Brill, 1987, ISBN 9004275134

Printed editions

[edit]The first printed edition of the Mishnah was published in Naples. There have been many subsequent editions, including the late 19th century Vilna edition, which is the basis of the editions now used by the religious public.

Vocalized editions were published in Italy, culminating in the edition of David ben Solomon Altaras, publ. Venice 1737. The Altaras edition was republished in Mantua in 1777, in Pisa in 1797 and 1810 and in Livorno in many editions from 1823 until 1936: reprints of the vocalized Livorno editions were published in Israel in 1913, 1962, 1968 and 1976. These editions show some textual variants by bracketing doubtful words and passages, though they do not attempt detailed textual criticism. The Livorno editions are the basis of the Sephardic tradition for recitation.

As well as being printed on its own, the Mishnah is included in all editions of the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmuds. Each paragraph is printed on its own, and followed by the relevant Gemara discussion. However, that discussion itself often cites the Mishnah line by line. While the text printed in paragraph form has generally been standardized to follow the Vilna edition, the text cited line by line in the Gemara often preserves important variants, which sometimes reflect the readings of older manuscripts.

The nearest approach to a critical edition is that of Hanoch Albeck. There is also an edition by Yosef Qafiḥ of the Mishnah together with the commentary of Maimonides, which compares the base text used by Maimonides with the Napoli and Vilna editions and other sources.

Oral traditions and pronunciation

[edit]The Mishnah was and still is traditionally studied through recitation (out loud). Jewish communities around the world preserved local melodies for chanting the Mishnah, and distinctive ways of pronouncing its words.

Many medieval manuscripts of the Mishnah are vowelized, and some of these, especially some fragments found in the Genizah, are partially annotated with Tiberian cantillation marks.[25]

Today, many communities have a special tune for the Mishnaic passage "Bammeh madliqin" in the Friday night service; there may also be tunes for Mishnaic passages in other parts of the liturgy, such as the passages in the daily prayers relating to sacrifices and incense and the paragraphs recited at the end of the Musaf service on Shabbat. Otherwise, there is often a customary intonation used in the study of Mishnah or Talmud, somewhat similar to an Arabic mawwal, but this is not reduced to a precise system like that for the Biblical books. (In some traditions this intonation is the same as or similar to that used for the Passover Haggadah.) Recordings have been made for Israeli national archives, and Frank Alvarez-Pereyre has published a book-length study of the Syrian tradition of Mishnah reading on the basis of these recordings.

Most vowelized editions of the Mishnah today reflect standard Ashkenazic vowelization, and often contain mistakes. The Albeck edition of the Mishnah was vocalized by Hanoch Yelon, who made careful eclectic use of both medieval manuscripts and current oral traditions of pronunciation from Jewish communities all over the world. The Albeck edition includes an introduction by Yelon detailing his eclectic method.

Two institutes at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem have collected major oral archives which hold extensive recordings of Jews chanting the Mishnah using a variety of melodies and many different kinds of pronunciation.[26] These institutes are the Jewish Oral Traditions Research Center and the National Voice Archives (the Phonoteca at the Jewish National and University Library). See below for external links.

As a historical source

[edit]Both the Mishnah and Talmud contain little serious biographical studies of the people discussed therein, and the same tractate will conflate the points of view of many different people. Yet, sketchy biographies of the Mishnaic sages can often be constructed with historical detail from Talmudic and Midrashic sources.

According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica (Second Edition), it is accepted that Judah the Prince added, deleted, and rewrote his source material during the process of redacting the Mishnah between the ending of the second century and the beginning of the 3rd century CE.[5] Modern authors who have provided examples of these changes include J.N. Epstein and S. Friedman.[27]

Following Judah the Prince's redaction there remained a number of different versions of the Mishnah in circulation. The Mishnah used in the Babylonian rabbinic community differing markedly from that used in the Palestinian one. Indeed within these rabbinic communities themselves there are indications of different versions being used for study. These differences are shown in divergent citations of individual Mishnah passages in the Talmud Yerushalmi and the Talmud Bavli, and in variances of medieval manuscripts and early editions of the Mishnah. The best known examples of these differences is found in J.N.Epstein's Introduction to the Text of the Mishnah (1948).[27]

Epstein has also concluded that the period of the Amoraim was one of further deliberate changes to the text of the Mishnah, which he views as attempts to return the text to what was regarded as its original form. These lessened over time, as the text of the Mishnah became more and more regarded as authoritative.[27]

Many modern historical scholars have focused on the timing and the formation of the Mishnah. A vital question is whether it is composed of sources which date from its editor's lifetime, and to what extent is it composed of earlier, or later sources. Are Mishnaic disputes distinguishable along theological or communal lines, and in what ways do different sections derive from different schools of thought within early Judaism? Can these early sources be identified, and if so, how? In response to these questions, modern scholars have adopted a number of different approaches.

- Some scholars hold that there has been extensive editorial reshaping of the stories and statements within the Mishnah (and later, in the Talmud.) Lacking outside confirming texts, they hold that we cannot confirm the origin or date of most statements and laws, and that we can say little for certain about their authorship. In this view, the questions above are impossible to answer. See, for example, the works of Louis Jacobs, Baruch M. Bokser, Shaye J. D. Cohen, Steven D. Fraade.

- Some scholars hold that the Mishnah and Talmud have been extensively shaped by later editorial redaction, but that it contains sources which we can identify and describe with some level of reliability. In this view, sources can be identified to some extent because each era of history and each distinct geographical region has its own unique feature, which one can trace and analyze. Thus, the questions above may be analyzed. See, for example, the works of Goodblatt, Lee Levine, David C. Kraemer and Robert Goldenberg.

- Some scholars hold that many or most of the statements and events described in the Mishnah and Talmud usually occurred more or less as described, and that they can be used as serious sources of historical study. In this view, historians do attempt to tease out later editorial additions leaving behind a possible historical text. See, for example, the works of Saul Lieberman, David Weiss Halivni, Avraham Goldberg and Dov Zlotnick.

Commentaries

[edit]

The main work discussing the Mishnah is the Talmud, as outlined. However, the Talmud is not usually viewed as a commentary on the Mishnah per se, because:[28] the Talmud also has many other goals; its analysis — "Gemara" — often entails long, tangential discussions; and neither version of the Talmud covers the entire Mishnah (each covers about 50–70% of the text).[29] As a result, numerous commentaries-proper on the Mishna have been written, typically intended to allow for the study of the work without requiring direct reference to (and facility for) the Gemara.[30]

Mishnah study, independent of the Talmud, was a marginal phenomenon before the late 15th century. The few commentaries that had been published tended to be limited to the tractates not covered by the Talmud, while Maimonides' commentary was written in Judeo-Arabic and thus inaccessible to many Jewish communities. Dedicated Mishnah study grew vastly in popularity beginning in the late 16th century, due to the kabbalistic emphasis on Mishnah study and as a reaction against the methods of pilpul; it was aided by the spread of Bertinoro's accessible Hebrew Mishnah commentary around this time.[31]

List of commentaries

[edit]Commentaries by Rishonim:

- In 1168, Maimonides (Rambam) published Kitab as-Siraj (The Book of the Lantern, Arabic: كتاب السراج) a comprehensive commentary on the Mishnah. It was written in Arabic using Hebrew letters (what is termed Judeo-Arabic) and was one of the first commentaries of its kind. In it, Rambam condensed the associated Talmudical debates, and offered his conclusions in a number of undecided issues. Of particular significance are the various introductory sections – as well as the introduction to the work itself[32] – these are widely quoted in other works on the Mishnah, and on the Oral law in general. Perhaps the most famous is his introduction to the tenth chapter of tractate Sanhedrin[33] where he enumerates the thirteen fundamental beliefs of Judaism.

- Rabbi Samson of Sens ("the Rash") was, apart from Maimonides, one of the few rabbis of the early medieval era to compose a Mishnah commentary on some tractates. It is printed in many editions of the Mishnah. It is interwoven with his commentary on major parts of the Tosefta.

- Asher ben Jehiel (Rosh)'s commentary on some tractates

- Menachem Meiri's commentary on most of the Mishnah, Beit HaBechirah, providing a digest of the Talmudic-discussion and Rishonim there

- An 11th-century CE commentary of the Mishnah, composed by Rabbi Nathan ben Abraham, President of the Academy in Eretz Israel. This relatively unknown commentary was first printed in Israel in 1955.

- A 12th-century Italian commentary of the Mishnah, made by Rabbi Isaac ben Melchizedek (only Seder Zera'im is known to have survived)

Prominent commentaries by early Acharonim:

- Rabbi Obadiah ben Abraham of Bertinoro (15th century) wrote one of the most popular Mishnah commentaries. He draws on Maimonides' work but also offers Talmudical material (in effect a summary of the Talmudic discussion) largely following the commentary of Rashi.[31] In addition to its role as a Mishnah commentary, this work is often used by students of Talmud as a review-text and is often referred to as "the Bartenura" or "the Ra'V".

- Yomtov Lipman Heller wrote a commentary called Tosefet Yom Tov. In the introduction Heller says that his aim is to add a supplement (tosefet) to Bertinoro's commentary in the style of the Tosafot. The glosses are sometimes quite detailed and analytic. In many compact Mishnah printings, a condensed version of his commentary, titled Ikar Tosefot Yom Tov, is featured.

Other commentaries by early Acharonim:

- Melechet Shlomo (Solomon Adeni; early 17th century)

- Kav veNaki (Amsterdam 1697) by R. Elisha en Avraham, a brief commentary on the entire Mishnah drawing from "the Bartenura", reprinted 20 times since its publication

- Hon Ashir by Immanuel Hai Ricchi (Amsterdam 1731)

- The Vilna Gaon (Shenot Eliyahu on parts of the Mishnah, and glosses Eliyaho Rabba, Chidushei HaGra, Meoros HaGra)

19th century:

- A (the) prominent commentary here is Tiferet Yisrael by Rabbi Israel Lipschitz. It is subdivided into two parts, one more general and the other more analytical, titled Yachin and Boaz respectively (after two large pillars in the Temple in Jerusalem). Although Rabbi Lipschutz has faced some controversy in certain Hasidic circles, he was greatly respected by such sages as Rabbi Akiva Eiger, whom he frequently cites, and is widely accepted in the Yeshiva world. The Tiferet Yaakov is an important gloss on the Tiferet Yisrael.

- Others from this time include:

- Rabbi Akiva Eiger (glosses, rather than a commentary)

- Mishnah Rishonah on Zeraim and the Mishnah Acharonah on Tohorot (Rav Efrayim Yitzchok from Premishla)

- Sidrei Tohorot on Kelim and Oholot (the commentary on the rest of Tohorot and on Eduyot is lost) by Gershon Henoch Leiner, the Radziner Rebbe

- Gulot Iliyot on Mikvaot, by Rav Dov Ber Lifshitz

- Ahavat Eitan by Rav Avrohom Abba Krenitz (the great grandfather of Rav Malkiel Kotler)

- Chazon Ish on Zeraim and Tohorot

20th century:

- Hayim Nahman Bialik's commentary to Seder Zeraim with vocalization (partially available here) in 1930 was one of the first attempts to create a modern commentary on Mishnah.[34] His decision to use the Vilna text (as opposed to a modern scholarly edition), and to write an introduction to every tractate describing its content and the relevant biblical material, influenced Hanoch Albeck, whose project was considered a continuation and expansion of Bialik's. [35]

- Hanoch Albeck's edition (1952–59) (vocalized by Hanoch Yelon), includes Albeck's extensive commentary on each Mishnah, as well as introductions to each tractate (Masekhet) and order (Seder). This commentary tends to focus on the meaning of the mishnayot themselves, with less reliance on the Gemara's interpretation and is, therefore, considered valuable as a tool for the study of Mishnah as an independent work. Especially important are the scholarly notes in the back of the commentary.

- Symcha Petrushka's commentary was written in Yiddish in 1945 (published in Montreal).[36] Its vocalization is supposed to be of high quality.

- The commentary by Rabbi Pinhas Kehati, which uses the Albeck text of the Mishnah, is written in Modern Israeli Hebrew and based on classical and contemporary works, has become popular in the late 20th century. The commentary is designed to make the Mishnah accessible to a wide readership. Each tractate is introduced with an overview of its contents, including historical and legal background material, and each Mishnah is prefaced by a thematic introduction. The current version of this edition is printed with the Bartenura commentary as well as Kehati's.

- The encyclopedic editions put out by Mishnat Rav Aharon (Beis Medrosho Govoah, Lakewood) on Peah, Sheviit, Challah, and Yadayim.

- Rabbi Yehuda Leib Ginsburg wrote a commentary on ethical issues, Musar HaMishnah. The commentary appears for the entire text except for Tohorot and Kodashim.

- Shmuel Safrai, Chana Safrai and Ze'ev Safrai have half completed a 45 volume socio-historic commentary "Mishnat Eretz Yisrael".[37]

- Mishnah Sdura, a format specially designed so as to facilitate recital and memorization, published by Rabbi E. Dordek in 1992. The layout is such that an entire chapter and its structure is readily visible, with each Mishnah, in turn, displayed in its component parts using line breaks (click on above image to view); includes tables summarizing each tractate, and the Kav veNaki commentary.

- ArtScroll's "Elucidated Mishnah", a phrase-by-phrase translation and elucidation based on the Bertinoro - following the format of the Schottenstein Edition Talmud. Its "Yad Avraham" commentary comprises supplementary explanations and notes, drawing on the Gemara and the other Mishnah commentaries and cross referencing the Shulchan Aruch as applicable. The work also includes a general introduction to each tractate. The Modern Hebrew (Ryzman) edition includes all these features.

Cultural references

[edit]A notable literary work on the composition of the Mishnah is Milton Steinberg's novel As a Driven Leaf.

See also

[edit]- Baraita

- Jewish commentaries on the Bible

- List of tractates, chapters, mishnahs and pages in the Talmud

- Mishnah Yomis – daily cycle of Mishna studying

- Mishneh Torah

- Tosefta

Notes

[edit]- ^ The same meaning is suggested by the term Deuterosis ("doubling" or "repetition" in Koine Greek) used in Roman law and Patristic literature. However, it is not always clear from the context if the reference is to the Mishnah or the Targum, which could be regarded as a "doubling" of the Torah reading.

- ^ a b c d Fine, Steven; Koller, Aaron J. (2014). Talmuda de-Eretz Israel: archaeology and the rabbis in late antique Palestine. Studia Judaica. Center for Israel studies. Boston: De Gruyter. pp. 231–237. ISBN 978-1-61451-485-5.

- ^ a b c d Maimonides. "Commentary on Tractate Avot with an Introduction (Shemona perakim)". World Digital Library. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ "Mishnah". Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ a b Skolnik, Fred; Berenbaum, Michael (2007). "Mishnah". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 14 (2 ed.). p. 319. ISBN 978-0-02-865942-8.. Heinrich Graetz, dissenting, places the Mishnah's compilation in 189 CE (see: H. Graetz, History of the Jews, vol. 6, Philadelphia 1898, p. 105 Archived 2022-11-02 at the Wayback Machine), and which date follows that penned by Rabbi Abraham ben David in his "Sefer HaKabbalah le-Ravad", or what was then anno 500 of the Seleucid era.

- ^ Trachtenberg, Joshua (13 February 2004) [Originally published 1939]. "Glossary of Hebrew Terms". Jewish Magic and Superstition. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press (published 2004). p. 333. ISBN 9780812218626. Retrieved Mar 14, 2023.

Mishna—the "Oral Law" forming basis of the Talmud; edited c. 220 C.E. by R. Judah HaNassi.

- ^ Eisenberg, Ronald L. (2004). "Rabbinic Literature". The JPS Guide to Jewish Traditions. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society. pp. 499–500.

- ^ "Maimonides on the Six Orders of the Mishnah". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved 2023-12-29.

- ^ "The Mishnah | Reform Judaism". www.reformjudaism.org. Retrieved 2023-12-29.

- ^ "יסוד המשנה ועריכתה" [Yesod Hamishna Va'arichatah] (in Hebrew). pp. 25–28. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Scherman, Nosson; Zlotowitz, Meir, eds. (2016). Shishah Sidre Mishnah = The Mishnah Elucidated: A phrase-by-phrase interpretive translation with basic commentary. Brooklyn, NY: Mesorah Publications. pp. 3–16. ISBN 978-1422614624. OCLC 872378784.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Temurah 14b; Gittin 60a.

- ^ Dr. Shayna Sheinfeld. "The Exclusivity of the Oral Law". Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ Strack, Hermann Leberecht (1945). Introduction to the Talmud and Midrash. Jewish Publication Society. pp. 11–12. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

[The Oral Law] was handed down by word of mouth during a long period. ... The first attempts to write down the traditional matter, there is reason to believe, date from the first half of the second post-Christian century.

Strack theorizes that the growth of a Christian canon (the New Testament) was a factor that influenced the Rabbis to record the oral law in writing. - ^ The theory that the destruction of the Temple and subsequent upheaval led to the committing of Oral Law into writing was first explained in the Epistle of Sherira Gaon and often repeated. See, for example, Grayzel, A History of the Jews, Penguin Books, 1984, p. 193.

- ^ Rabinowich, Nosson Dovid, ed. (1988). The Iggeres of Rav Sherira Gaon. Jerusalem. pp. 28–29. OCLC 20044324. (html)

- ^ Though as shown below, there is some disagreement about whether the Mishnah was originally put in writing.

- ^ Schloss, Chaim (2002). 2000 Years of Jewish History: From the Destruction of the Second Bais Hamikdash Until the Twentieth Century. Philipp Feldheim. p. 68. ISBN 978-1583302149. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

Despite the many secular demands on his time, Rabbeinu Shmuel authored a number of books. The most famous is the Mevo HaTalmud, an introduction to the study of the Talmud which clarifies the language and structure which can be so confusing to beginners. In addition, the Mevo HaTalmud describes the development of the Mishnah and the Gemara and lists the Tannaim and Amoraim who were instrumental in preparing the Talmud.

- ^ Lex Robeberg. "Why The Mishnah Is the Best Jewish Book You've Never Read". myjewishlearning.com. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ Outhwaite, Ben. "Mishnah". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ^ The plural term (singular tanna) for the Rabbinic sages whose views are recorded in the Mishnah; from the Aramaic root tanna (תנא) equivalent for the Hebrew root shanah (שנה), as in Mishnah.

- ^ Abraham ben David calculated the date 189 CE. Seder Ha-Kabbalah Leharavad, Jerusalem 1971, p.16 (Hebrew)

- ^ According to the Epistle (Iggeret) of Sherira Gaon.

- ^ This theory was held by David Zvi Hoffman, and is repeated in the introduction to Herbert Danby's Mishnah translation.

- ^ Yeivin, Israel (1960). Cantillation of the Oral Law (in Hebrew). Leshonenu 24. pp. 47–231.

- ^ Shelomo Morag, The Samaritan and Yemenite Tradition of Hebrew (published in: The Traditions of Hebrew and Aramaic of the Jews of Yemen; ed. Yosef Tobi), Tel Aviv 2001, p. 183 (note 12)

- ^ a b c Skolnik, Fred; Berenbaum, Michael (2007). "The Traditional Interpretation of the Mishnah". Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 14 (2 ed.). p. 327. ISBN 978-0-02-865942-8.

- ^ See for example § "Both Broad and Deep" under Gemara: The Essence of the Talmud, myjewishlearning.com

- ^ See summary of per-tractate coverage: Birnbaum, Philip (1975). "Tractates". A Book of Jewish Concepts. New York, NY: Hebrew Publishing Company. p. 373-374. ISBN 088482876X.

- ^ See this discussion on Moses Maimonides commentary

- ^ a b Coffee with the Bartenura

- ^ "הקדמה לפירוש המשנה" [Introduction to the Mishnah Commentary]. Daat.ac.il (in Hebrew). Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ "הקדמת רמב"ם לפרק "חלק"" [Rambam's introduction to the chapter "Chelek"]. Daat.ac.il (in Hebrew). Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Mordechai Meir, “Shisha Sidrei Ha-Mishna Menukadim U-mefurashim al Yedei Chaim Nachman Bialik: Kavim Le-mifalo Ha-nishkach shel Bialik,” Netuim 16 (5770), pp.191-208, available at: http://www.herzog.ac.il/vtc/tvunot/netuim16_meir.pdf Archived 2022-06-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hanoch Albeck, 'Introduction', Shisha Sidre Mishnah (Jerusalem: Mossad Bialik,)1:9.

- ^ Margolis, Rebecca (2009). "Translating Jewish Poland into Canadian Yiddish: Symcha Petrushka's Mishnayes" (PDF). TTR: traduction, terminologie, rédaction. 22 (2): 183–209. doi:10.7202/044829ar. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ See e.g. Mishnat Eretz Yisrael on Berakhot

References

[edit]English translations

[edit]- Shaye J. D. Cohen, Robert Goldenberg, Hayim Lapin (eds.), The Oxford Annotated Mishnah: A New Translation of the Mishnah With Introductions and Notes, New York, Oxford University Press, 2022.

- Philip Blackman. Mishnayoth. The Judaica Press, Ltd., reprinted 2000 (ISBN 978-0-910818-00-1). Online PDF at HebrewBooks: Zeraim, Moed, Nashim, Nezikin, Kodashim, Tehorot.

- Herbert Danby. The Mishnah. Oxford, 1933 (ISBN 0-19-815402-X).

- Jacob Neusner. The Mishnah: A New Translation. New Haven, reprint 1991 (ISBN 0-300-05022-4).

- Isidore Epstein (ed.). Soncino Talmud. London, 1935-1952. Includes Mishnah-translations for those tractates without Gemara.