During the three centuries that bracketed the Early Christian Movement, the great parties and sects of Judaism were developed into the form in which we find them described in the New Testament period. By far the most important of these developments was the growth of the Pharissic party, which first emerged distinctly in the reign of the Maccabbean prince John Hyrcanus (135 BCT - 105 BCT).

An older party, which continued to play a prominent role as the opponents of the popular and nationalist Pharisees, was that of the Sadducees. This party was mainly recruited from the priests, and represented priestly tradition and privilege, as these had grown up in conjunction with the Temple and its culture and traditions. Though the Sadducees embraced within their ranks the high priestly families and their adherents (i.e., the priestly aristocracy), and though these often included a worldly element, Sadduceeism was by no means deficient in piety. It often represented the conservative type of Judaism at its best.

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Pharisees פרושים | |

|---|---|

| Historical leaders | |

| Founded | 167 BCE |

| Dissolved | 73 CE |

| Headquarters | Jerusalem |

| Ideology | |

| Religion | Rabbinic Judaism |

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Pharisee, member of a Jewish religious party that flourished in Palestine during the latter part of the Second Temple period (515 bce–70 ce). The Pharisees’ insistence on the binding force of oral tradition (“the unwritten Torah”) remains a basic tenet of Jewish theological thought. When the Mishna (the first constituent part of the Talmud) was compiled about 200 ce, it incorporated the teachings of the Pharisees on Jewish law.

The Pharisees (Hebrew: Perushim) emerged as a distinct group shortly after the Maccabean revolt, about 165–160 bce; they were, it is generally believed, spiritual descendants of the Hasideans. The Pharisees emerged as a party of laymen and scribes in contradistinction to the Sadducees—i.e., the party of the high priesthood that had traditionally provided the sole leadership of the Jewish people. The basic difference that led to the split between the Pharisees and the Sadducees lay in their respective attitudes toward the Torah (the first five books of the Bible) and the problem of finding in it answers to questions and bases for decisions about contemporary legal and religious matters arising under circumstances far different from those of the time of Moses. In their response to this problem, the Sadducees, on the one hand, refused to accept any precept as binding unless it was based directly on the Torah—i.e., the Written Law. The Pharisees, on the other hand, believed that the Law that God gave to Moses was twofold, consisting of the Written Law and the Oral Law—i.e., the teachings of the prophets and the oral traditions of the Jewish people. Whereas the priestly Sadducees taught that the written Torah was the only source of revelation, the Pharisees admitted the principle of evolution in the Law: humans must use their reason in interpreting the Torah and applying it to contemporary problems.

Rather than blindly follow the letter of the Law even if it conflicted with reason or conscience, the Pharisees harmonized the teachings of the Torah with their own ideas or found their own ideas suggested or implied in it. They interpreted the Law according to its spirit. When in the course of time a law had been outgrown or superseded by changing conditions, they gave it a new and more-acceptable meaning, seeking scriptural support for their actions through a ramified system of hermeneutics. It was because of this progressive tendency of the Pharisees that their interpretation of the Torah continued to develop and has remained a living force in Judaism.

The Pharisees were primarily not a political party but a society of scholars and pietists. They enjoyed a large popular following, and in the New Testament they appear as spokesmen for the majority of the population. About 100 bce a long struggle ensued as the Pharisees tried to democratize the Jewish religion and remove it from the control of the Temple priests. The Pharisees asserted that God could and should be worshipped even away from the Temple and outside Jerusalem. To the Pharisees, worship consisted not in bloody sacrifices—the practice of the Temple priests—but in prayer and in the study of God’s law. Hence, the Pharisees fostered the synagogue as an institution of religious worship, outside and separate from the Temple. The synagogue may thus be considered a Pharasaic institution, since the Pharisees developed it, raised it to high eminence, and gave it a central place in Jewish religious life.

The active period of Pharasaism, the most-influential movement in the development of Orthodox Judaism, extended well into the 2nd and 3rd centuries ce. The Pharisees preserved and transmitted Judaism through the flexibility they gave to Jewish scriptural interpretation in the face of changing historical circumstances. The efforts they devoted to education also had a seminal importance in subsequent Jewish history. After the destruction of the Second Temple and the fall of Jerusalem in 70 ce, it was the synagogue and the schools of the Pharisees that continued to function and to promote Judaism in the long centuries following the Diaspora.

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

The Pharisees (/ˈfærəsiːz/; Hebrew: פְּרוּשִׁים, romanized: Pərūšīm, lit. 'separated ones') were a Jewish social movement and a school of thought in the Levant during the time of Second Temple Judaism. Following the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD, Pharisaic beliefs became the foundational, liturgical, and ritualistic basis for Rabbinic Judaism. Although the group does not exist anymore, their traditions are considered important among all various Jewish religious movements.

Conflicts between Pharisees and Sadducees took place in the context of much broader and longstanding social and religious conflicts among Jews, made worse by the Roman conquest.[2] One conflict was cultural, between those who favored Hellenization (the Sadducees) and those who resisted it (the Pharisees). Another was juridical-religious, between those who emphasized the importance of the Temple with its rites and services, and those who emphasized the importance of other Mosaic Laws. A specifically religious point of conflict involved different interpretations of the Torah and how to apply it to current Jewish life, with Sadducees recognizing only the Written Torah and rejecting Prophets, Writings, and doctrines such as the Oral Torah and the resurrection of the dead.

Josephus (c. 37 – c. 100 CE), believed by many historians to have been a Pharisee, estimated the total Pharisee population before the fall of the Second Temple to be around 6,000.[3] He claimed that the Pharisees' influence over the common people was so great that anything they said against the king or the high priest was believed,[4] apparently in contrast to the more elite Sadducees, who were the upper class. Pharisees claimed Mosaic authority for their interpretation[5] of Jewish religious law, while Sadducees represented the authority of the priestly privileges and prerogatives established since the days of Solomon, when Zadok, their ancestor, officiated as high priest.

Pharisees are notable by the numerous references to them in the New Testament. While the writers record hostilities between the Pharisees and Jesus, they also reference Pharisees who believed in him, including Nicodemus, who said it is known that Jesus is a teacher sent from God,[6] Joseph of Arimathea, who was a disciple,[7] and an unknown number of "those of the party of the Pharisees who believed",[8] among them the Apostle Paul – a student of Gamaliel,[9] who warned the Sanhedrin that opposing the disciples of Jesus could prove to be tantamount to opposing God.[10][11][12]

Etymology

[edit]"Pharisee" is derived from Ancient Greek Pharisaios (Φαρισαῖος),[13] from Aramaic Pərīšā (פְּרִישָׁא), plural Pərīšayyā (פְּרִישַׁיָּא), meaning "set apart, separated", related to Hebrew Pārūš (פָּרוּשׁ), plural Pərūšīm (פְּרוּשִׁים), the Qal passive participle of the verb pāraš (פָּרַשׁ).[14][15] It may refer to their separation from Gentiles, sources of ritual impurity or from irreligious Jews.[16]: 159 Alternatively, it may have a particular political meaning as "separatists" due to their division from the Sadducee elite, with Yitzhak Isaac Halevi characterizing the Sadducees and Pharisees as political sects, not religious ones.[17] Scholar Thomas Walter Manson and Talmud-expert Louis Finkelstein suggest that "Pharisee" derives from the Aramaic words pārsāh or parsāh, meaning "Persian" or "Persianizer",[18][19] based on the demonym pārsi, meaning 'Persian' in the Persian language and further akin to Pārsa and Fārs.[20] Harvard University scholar Shaye J. D. Cohen denies this, stating: "Practically all scholars now agree that the name "Pharisee" derives from the Hebrew and Aramaic parush or persushi."[16]

Sources

[edit]The first historical mention of the Pharisees and their beliefs comes in the four gospels and the Acts of the Apostles, in which both their meticulous adherence to their interpretation of the Torah as well as their eschatological views are described. A later historical mention of the Pharisees comes from the Jewish-Roman historian Josephus (37–100 CE) in a description of the "four schools of thought", or "four sects", into which he divided the Jews in the 1st century CE. (The other schools were the Essenes, who were generally apolitical and who may have emerged as a sect of dissident priests who rejected either the Seleucid-appointed or the Hasmonean high priests as illegitimate; the Sadducees, the main antagonists of the Pharisees; and the Zealots.[21]) Other sects may have emerged at this time, such as the Early Christians in Jerusalem and the Therapeutae in Egypt. However, their status as Jews is unclear.

The Books of the Maccabees, two deuterocanonical books in the Bible, focus on the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucids under king Antiochus IV Epiphanes and concludes with the defeat of General Nicanor, in 161 BCE by Judas Maccabeus, the hero of the work. It included several theological points: prayer for the dead, the last judgment, intercession of saints, and martyrology. The New Testament apocrypha known as the Gospel of Peter also alludes to the Pharisees.[22]

Judah ha-Nasi redacted the Mishnah, an authoritative codification of Pharisaic interpretations, around 200 CE. Most of the authorities quoted in the Mishnah lived after the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE; it thus marks the beginning of the transition from Pharisaic to Rabbinic Judaism. The Mishnah was supremely important because it compiled the oral interpretations and traditions of the Pharisees and, later on, the rabbis, into a single authoritative text, thus allowing oral tradition within Judaism to survive the destruction of the Second Temple.

However, none of the Rabbinic sources include identifiable eyewitness accounts of the Pharisees and their teachings.[23]

History

[edit]From c. 600 BC – c. 160 BC

[edit]The deportation and exile of an unknown number of Jews of the ancient Kingdom of Judah to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar II, starting with the first deportation in 597 BCE[24] and continuing after the fall of Jerusalem and destruction of the Temple in 587 BCE,[25] resulted in dramatic changes to Jewish culture and religion. During the 70-year exile in Babylon, Jewish houses of assembly (known in Hebrew as a beit knesset or in Greek as a synagogue) and houses of prayer (Hebrew Beit Tefilah; Greek προσευχαί, proseuchai) were the primary meeting places for prayer, and the house of study (beit midrash) was the counterpart for the synagogue.[citation needed]

In 539 BCE the Persians conquered Babylon, and in 537 BCE Cyrus the Great allowed Jews to return to Judea and rebuild the Temple. He did not, however, allow the restoration of the Judean monarchy, which left the Judean priests as the dominant authority. Without the constraining power of the monarchy, the authority of the Temple in civic life was amplified. It was around this time that the Sadducee party emerged as the party of priests and allied elites. However, the Second Temple, which was completed in 515 BCE, had been constructed under the auspices of a foreign power, and there were lingering questions about its legitimacy.[citation needed] This provided the condition for the development of various sects or "schools of thought," each of which claimed exclusive authority to represent "Judaism," and which typically shunned social intercourse, especially marriage, with members of other sects. In the same period, the council of sages known as the Sanhedrin may have codified and canonized the latter sections of the Hebrew Bible (Nakh), from which, following the return from Babylon, the Torah was read publicly on market-days.[citation needed]

The Temple was no longer the only institution for Jewish religious life. After the building of the Second Temple in the time of Ezra the Scribe, the houses of study and worship remained important secondary institutions in Jewish life. Outside Judea, the synagogue was often called a house of prayer. While most Jews could not regularly attend the Temple service, they could meet at the synagogue for morning, afternoon and evening prayers. On Mondays, Thursdays and Shabbat, a weekly Torah portion was read publicly in the synagogues, following the tradition of public Torah readings instituted by Ezra.[26]

Although priests controlled the rituals of the Temple, the scribes and sages, later called rabbis (Hebrew for "Teacher/master"), dominated the study of the Torah. These men maintained an oral tradition that they believed had originated at Mount Sinai alongside the Torah of Moses; a God-given interpretation of the Torah.[citation needed]

The Hellenistic period of Jewish history began when Alexander the Great conquered Persia in 332 BCE. The rift between the priests and the sages developed during this time, when Jews faced new political and cultural struggles. This created a sort of schism in the Jewish community. After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, Judea was ruled by the Egyptian-Hellenic Ptolemies until 198 BCE, when the Syrian-Hellenic Seleucid Empire, under Antiochus III, seized control. Then, in 167 BCE, the Seleucid king Antiochus IV invaded Judea, entered the Temple, and stripped it of money and ceremonial objects. He imposed a program of forced Hellenization, requiring Jews to abandon their own laws and customs, thus precipitating the Maccabean Revolt. Jerusalem was liberated in 165 BCE and the Temple was restored. In 141 BCE an assembly of priests and others affirmed Simon Maccabeus as high priest and leader, in effect establishing the Hasmonean dynasty.

Emergence of the Pharisees

[edit]

After defeating the Seleucid forces, Judas Maccabaeus's nephew John Hyrcanus established a new monarchy in the form of the priestly Hasmonean dynasty in 152 BCE, thus establishing priests as political as well as religious authorities. Although the Hasmoneans were considered heroes for resisting the Seleucids, their reign lacked the legitimacy conferred by descent from the Davidic dynasty of the First Temple era.[27]

The Pharisees emerged[when?] largely out of the group of scribes and sages.[citation needed] Some scholars observe significant Idumean influences in the development of Pharisaical Judaism.[28] The Pharisees, among other Jewish sects, were active from the middle of the second century BCE until the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE.[16]: 143 Josephus first mentions them in connection with Jonathan, the successor of Judas Maccabeus.[29] One of the factors that distinguished the Pharisees from other groups prior to the destruction of the Temple was their belief that all Jews had to observe the purity laws (which applied to the Temple service) outside the Temple. The major difference, however, was the continued adherence of the Pharisees to the laws and traditions of the Jewish people in the face of assimilation. As Josephus noted, the Pharisees were considered the most expert and accurate expositors of Jewish law.[citation needed]

Josephus indicates that the Pharisees received the backing and good-will of the common people,[30] apparently in contrast to the more elite Sadducees associated with the ruling classes. In general, whereas the Sadducees were aristocratic monarchists, the Pharisees were eclectic, popular, and more democratic.[31] The Pharisaic position is exemplified by the assertion that "A learned mamzer takes precedence over an ignorant High Priest." (A mamzer, literally, bastard, according to the Pharisaic definition, is an outcast child born of a forbidden relationship, such as adultery or incest, in which marriage of the parents could not lawfully occur. The word is often, but incorrectly, translated as "illegitimate".)[32]

Sadducees rejected the Pharisaic tenet of an Oral Torah, creating two Jewish understandings of the Torah. An example of this differing approach is the interpretation of, "an eye in place of an eye". The Pharisaic understanding was that the value of an eye was to be paid by the perpetrator.[33] In the Sadducees' view the words were given a more literal interpretation, in which the offender's eye would be removed.[34]

The sages of the Talmud see a direct link between themselves and the Pharisees, and historians generally consider Pharisaic Judaism to be the progenitor of Rabbinic Judaism, that is normative, mainstream Judaism after the destruction of the Second Temple. All mainstream forms of Judaism today consider themselves heirs of Rabbinic Judaism and, ultimately, the Pharisees.

The Hasmonean period

[edit]Although the Pharisees did not support the wars of expansion of the Hasmoneans and the forced conversions of the Idumeans, the political rift between them became wider when a Pharisee named Eleazar insulted the Hasmonean ethnarch John Hyrcanus at his own table, suggesting that he should abandon his role as High Priest due to a rumour, probably untrue, that he had been conceived while his mother was a prisoner of war. In response, he distanced himself from the Pharisees.[35][36]

After the death of John Hyrcanus, his younger son Alexander Jannaeus made himself king and openly sided with the Sadducees by adopting their rites in the Temple. His actions caused a riot in the Temple, and led to a brief civil war that ended with a bloody repression of the Pharisees. However, on his deathbed Jannaeus advised his widow, Salome Alexandra, to seek reconciliation with the Pharisees. Her brother was Shimon ben Shetach, a leading Pharisee. Josephus attests that Salome was favorably inclined toward the Pharisees, and their political influence grew tremendously under her reign, especially in the Sanhedrin or Jewish Council, which they came to dominate.

After her death her elder son Hyrcanus II was generally supported by the Pharisees. Her younger son, Aristobulus II, was in conflict with Hyrcanus, and tried to seize power. The Pharisees seemed to be in a vulnerable position at this time.[37] The conflict between the two sons culminated in a civil war that ended when the Roman general Pompey intervened, and captured Jerusalem in 63 BCE.

Josephus' account may overstate the role of the Pharisees. He reports elsewhere that the Pharisees did not grow to power until the reign of Queen Salome Alexandra.[38] As Josephus was himself a Pharisee, his account might represent a historical creation meant to elevate the status of the Pharisees during the height of the Hasmonean Dynasty.[39]

Later texts like the Mishnah and the Talmud record a host of rulings by rabbis, some of whom are believed to be from among the Pharisees, concerning sacrifices and other ritual practices in the Temple, torts, criminal law, and governance. In their day, the influence of the Pharisees over the lives of the common people was strong and their rulings on Jewish law were deemed authoritative by many.[citation needed]

The Roman period

[edit]

According to Josephus, the Pharisees appeared before Pompey asking him to interfere and restore the old priesthood while abolishing the royalty of the Hasmoneans altogether.[40] Pharisees also opened Jerusalem's gates to the Romans, and actively supported them against the Sadducean faction.[41] When the Romans finally broke the entrance to the Jerusalem's Temple, the Pharisees killed the priests who were officiating the Temple services on Saturday.[42] They regarded Pompey's defilement of the Temple in Jerusalem as a divine punishment of Sadducean misrule. Pompey ended the monarchy in 63 BCE and named Hyrcanus II high priest and ethnarch (a lesser title than "king").[43] Six years later Hyrcanus was deprived of the remainder of political authority and ultimate jurisdiction was given to the Proconsul of Syria, who ruled through Hyrcanus's Idumaean associate Antipater, and later Antipater's two sons Phasael (military governor of Judea) and Herod (military governor of Galilee). In 40 BCE Aristobulus's son Antigonus overthrew Hyrcanus and named himself king and high priest, and Herod fled to Rome.

In Rome, Herod sought the support of Mark Antony and Octavian, and secured recognition by the Roman Senate as king, confirming the termination of the Hasmonean dynasty. According to Josephus, Sadducean opposition to Herod led him to treat the Pharisees favorably.[44] Herod was an unpopular ruler, perceived as a Roman puppet. Despite his restoration and expansion of the Second Temple, Herod's notorious treatment of his own family and of the last Hasmonaeans further eroded his popularity. According to Josephus, the Pharisees ultimately opposed him and thus fell victims (4 BCE) to his bloodthirstiness.[45] The family of Boethus, whom Herod had raised to the high-priesthood, revived the spirit of the Sadducees, and thenceforth the Pharisees again had them as antagonists.[46]

While it stood, the Second Temple remained the center of Jewish ritual life. Jews were required to travel to Jerusalem and offer sacrifices at the Temple three times a year: Pesach (Passover), Shavuot (the Feast of Weeks), and Sukkot (the Feast of Tabernacles). The Pharisees, like the Sadducees, were politically quiescent, and studied, taught, and worshiped in their own way. At this time serious theological differences emerged between the Sadducees and Pharisees. The notion that the sacred could exist outside the Temple, a view central to the Essenes, was shared and elevated by the Pharisees.[citation needed]

Legacy

[edit]At first, the values of the Pharisees developed through their sectarian debates with the Sadducees; then they developed through internal, non-sectarian debates over the law as an adaptation to life without the Temple, and life in exile, and eventually, to a more limited degree, life in conflict with Christianity.[47] These shifts mark the transformation of Pharisaic to Rabbinic Judaism.

Beliefs

[edit]No single tractate of the key Rabbinic texts, the Mishnah and the Talmud, is devoted to theological issues; these texts are concerned primarily with interpretations of Jewish law, and anecdotes about the sages and their values. Only one chapter of the Mishnah deals with theological issues; it asserts that three kinds of people will have no share in "the world to come:" those who deny the resurrection of the dead, those who deny the divinity of the Torah, and Epicureans (who deny divine supervision of human affairs). Another passage suggests a different set of core principles: normally, a Jew may violate any law to save a life, but in Sanhedrin 74a, a ruling orders Jews to accept martyrdom rather than violate the laws against idolatry, murder, or adultery. (Judah ha-Nasi, however, said that Jews must "be meticulous in small religious duties as well as large ones, because you do not know what sort of reward is coming for any of the religious duties," suggesting that all laws are of equal importance).

Monotheism

[edit]One belief central to the Pharisees which was shared by all Jews of the time is monotheism. This is evident in the practice of reciting the Shema, a prayer composed of select verses from the Torah (Deuteronomy 6:4), at the Temple and in synagogues; the Shema begins with the verses, "Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God; the Lord is one." According to the Mishna, these passages were recited in the Temple along with the twice-daily Tamid offering; Jews in the diaspora, who did not have access to the Temple, recited these passages in their houses of assembly. According to the Mishnah and Talmud, the men of the Great Assembly instituted the requirement that Jews both in Judea and in the diaspora pray three times a day (morning, afternoon and evening), and include in their prayers a recitation of these passages in the morning (Shacharit) and evening (Ma'ariv) prayers.

Wisdom

[edit]Pharisaic wisdom was compiled in one book of the Mishna, Pirkei Avot. The Pharisaic attitude is perhaps[citation needed] best exemplified by a story about the sages Hillel the Elder and Shammai, who both lived in the latter half of the 1st century BCE. A Gentile once challenged Shammai to teach him the wisdom of the Torah while he stood on one foot. Shammai drove him away. The same gentile approached Hillel and asked of him the same thing. Hillel chastised him gently by saying, "What is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow. That is the whole Torah; the rest is the explanation – now go and study."[48]

Free will and predestination

[edit]According to Josephus, whereas the Sadducees believed that people have total free will and the Essenes believed that all of a person's life is predestined, the Pharisees believed that people have free will but that God also has foreknowledge of human destiny. This also accords with the statement in Pirkei Avot 3:19, "Rabbi Akiva said: All is foreseen, but freedom of choice is given". According to Josephus, Pharisees were further distinguished from the Sadducees in that Pharisees believed in the resurrection of the dead.

The afterlife

[edit]Unlike the Sadducees, who are generally held to have rejected any existence after death, the sources vary on the beliefs of the Pharisees on the afterlife. According to the New Testament the Pharisees believed in the resurrection of the dead.[49] According to Josephus, who himself was a Pharisee, the Pharisees held that only the soul was immortal and the souls of good people would be resurrected or reincarnated[50] and "pass into other bodies," while "the souls of the wicked will suffer eternal punishment."[51] Paul the Apostle declared himself to be a Pharisee even after his belief in Jesus.[52][53]

Practices

[edit]A kingdom of priests

[edit]Fundamentally, the Pharisees continued a form of Judaism that extended beyond the Temple, applying Jewish law to mundane activities in order to sanctify the everyday world. This was monumental as a practice during this era, as it helped the Jews of the time to truly align themselves with the law, applying even to the mundanities of life. This was a more participatory (or "democratic") form of Judaism, in which rituals were not monopolized by an inherited priesthood but rather could be performed by all adult Jews individually or collectively, whose leaders were not determined by birth but by scholarly achievement.[citation needed]

Many, including some scholars, have characterized the Sadducees as a sect that interpreted the Torah literally, and the Pharisees as interpreting the Torah liberally. R' Yitzhak Isaac Halevi suggests that this was not, in fact, a matter of religion. He claims that the complete rejection of Judaism would not have been tolerated under the Hasmonean rule and therefore Hellenists maintained that they were rejecting not Judaism but Rabbinic law. Thus, the Sadducees were in fact a political party not a religious sect.[17] However, according to Jacob Neusner, this view is a distortion. He suggests that two things fundamentally distinguished the Pharisaic from the Sadducean approach to the Torah. First, Pharisees believed in a broad and literal interpretation of Exodus (19:3–6), "you shall be my own possession among all peoples; for all the earth is mine, and you shall be to me a kingdom of priests and a holy nation,"[54]: 40 and the words of 2 Maccabees (2:17): "God gave all the people the heritage, the kingdom, the priesthood, and the holiness."

The Pharisees believed that the idea that all of the children of Israel were to be like priests was expressed elsewhere in the Torah, for example, when the Law itself was transferred from the sphere of the priesthood to every man in Israel.[55] Moreover, the Torah already provided ways for all Jews to lead a priestly life: the laws of kosher animals were perhaps[citation needed] intended originally for the priests, but were extended to the whole people;[56] similarly the prohibition of cutting the flesh in mourning for the dead.[57] The Pharisees believed that all Jews in their ordinary life, and not just the Temple priesthood or Jews visiting the Temple, should observe rules and rituals concerning purification.[citation needed]

The Oral Torah

[edit]The standard view is that the Pharisees differed from Sadducees in the sense that they accepted the Oral Torah in addition to the Scripture. Anthony J. Saldarini argues that this assumption has neither implicit nor explicit evidence. A critique of the ancient interpretations of the Bible are distant from what modern scholars consider literal. Saldarini states that the Oral Torah did not come about until the third century CE, although there was an unstated idea about it in existence. Every Jewish community in a way possessed their own version of the Oral Torah which governed their religious practices. Josephus stated that the Sadducees only followed literal interpretations of the Torah. To Saldarini, this only means that the Sadducees followed their own way of Judaism and rejected the Pharisaic version of Judaism.[58] To Rosemary Ruether, the Pharisaic proclamation of the Oral Torah was their way of freeing Judaism from the clutches of Aaronite priesthood, represented by the Sadducees. The Oral Torah was to remain oral but was later given a written form. It did not refer to the Torah in a status as a commentary, rather had its own separate existence which allowed Pharisaic innovations.[59]

The sages of the Talmud believed that the Oral law was simultaneously revealed to Moses at Sinai, and the product of debates among rabbis. Thus, one may conceive of the "Oral Torah" as both based on the fixed text and as an ongoing process of analysis and argument in which God is actively involved; it was this ongoing process that was revealed at Sinai along with the scripture, and by participating in this ongoing process rabbis and their students are actively participating in God's ongoing act of revelation.[citation needed]

As Jacob Neusner has explained, the schools of the Pharisees and rabbis were and are holy:

The commitment to relate religion to daily life through the law has led some (notably, Saint Paul and Martin Luther) to infer that the Pharisees were more legalistic than other sects in the Second Temple Era. The authors of the Gospels present Jesus as speaking harshly against some Pharisees (Josephus does claim that the Pharisees were the "strictest" observers of the law).[60] Yet, as Neusner has observed, Pharisaism was but one of many "Judaisms" in its day,[61] and its legal interpretation are what set it apart from the other sects of Judaism.[62]

Innovators or preservers

[edit]The Mishna in the beginning of Avot and (in more detail) Maimonides in his Introduction to Mishneh Torah records a chain of tradition (mesorah) from Moses at Mount Sinai down to R' Ashi, redactor of the Talmud and last of the Amoraim. This chain of tradition includes the interpretation of unclear statements in the Bible (e.g. that the "fruit of a beautiful tree" refers to a citron as opposed to any other fruit), the methods of textual exegesis (the disagreements recorded in the Mishna and Talmud generally focus on methods of exegesis), and Laws with Mosaic authority that cannot be derived from the Biblical text (these include measurements (e.g. what amount of a non-kosher food must one eat to be liable), the amount and order of the scrolls to be placed in the phylacteries, etc.).

The Pharisees were also innovators in that they enacted specific laws as they saw necessary according to the needs of the time. These included prohibitions to prevent an infringement of a biblical prohibition (e.g. one does not take a Lulav on Shabbat "Lest one carry it in the public domain") called gezeirot, among others. The commandment to read the Megillah (Book of Esther) on Purim and to light the Menorah on Hanukkah are Rabbinic innovations. Much of the legal system is based on "what the sages constructed via logical reasoning and from established practice".[63] Also, the blessings before meals and the wording of the Amidah. These are known as Takanot. The Pharisees based their authority to innovate on the verses: "....according to the word they tell you... according to all they instruct you. According to the law they instruct you and according to the judgment they say to you, you shall do; you shall not divert from the word they tell you, either right or left" (Deuteronomy 17:10–11) (see Encyclopedia Talmudit entry "Divrei Soferim").

In an interesting twist, Abraham Geiger posits that the Sadducees were the more hidebound adherents to an ancient Halacha whereas the Pharisees were more willing to develop Halacha as the times required. See however, Bernard Revel's "Karaite Halacha" which rejects many of Geiger's proofs.

Significance of debate and study of the law

[edit]Just as important as (if not more important than) any particular law was the value the rabbis placed on legal study and debate. The sages of the Talmud believed that when they taught the Oral Torah to their students, they were imitating Moses, who taught the law to the children of Israel. Moreover, the rabbis believed that "the heavenly court studies Torah precisely as does the earthly one, even arguing about the same questions."[54]: 8 Thus, in debating and disagreeing over the meaning of the Torah or how best to put it into practice, no rabbi felt that he (or his opponent) was rejecting God or threatening Judaism; on the contrary, it was precisely through such arguments that the rabbis imitated and honored God.

One sign of the Pharisaic emphasis on debate and differences of opinion is that the Mishnah and Talmud mark different generations of scholars in terms of different pairs of contending schools. In the first century, for example, the two major Pharisaic schools were those of Hillel and Shammai. After Hillel died in 20 CE, Shammai assumed the office of president of the Sanhedrin until he died in 30 CE. Followers of these two sages dominated scholarly debate over the following decades. Although the Talmud records the arguments and positions of the school of Shammai, the teachings of the school of Hillel were ultimately taken as authoritative.[citation needed]

From Pharisees to rabbis

[edit]Following the Jewish–Roman wars, revolutionaries like the Zealots had been crushed by the Romans, and had little credibility (the last Zealots died at Masada in 73 CE).[dubious – discuss] Similarly, the Sadducees, whose teachings were closely connected to the Temple, disappeared with the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. The Essenes too disappeared, perhaps because their teachings so diverged from the concerns of the times, perhaps because they were sacked by the Romans at Qumran.[64][65]

Of all the major Second Temple sects, only the Pharisees remained. Their vision of Jewish law as a means by which ordinary people could engage with the sacred in their daily lives was a position meaningful to the majority of Jews. Such teachings extended beyond ritual practices. According to the classic midrash in Avot D'Rabbi Nathan (4:5):

Following the destruction of the Temple, Rome governed Judea through a Procurator at Caesarea and a Jewish Patriarch and levied the Fiscus Judaicus. Yohanan ben Zakkai, a leading Pharisee, was appointed the first Patriarch (the Hebrew word, Nasi, also means prince, or president), and he reestablished the Sanhedrin at Yavneh (see the related Council of Jamnia) under Pharisee control. Instead of giving tithes to the priests and sacrificing offerings at the (now-destroyed) Temple, the rabbis instructed Jews to give charity. Moreover, they argued that all Jews should study in local synagogues, because Torah is "the inheritance of the congregation of Jacob" (Deuteronomy 33:4).[citation needed]

After the destruction of the First Temple, Jews believed that God would forgive them and enable them to rebuild the Temple – an event that actually occurred within three generations. After the destruction of the Second Temple, Jews wondered whether this would happen again. When the Emperor Hadrian threatened to rebuild Jerusalem as a pagan city dedicated to Jupiter, in 132, Aelia Capitolina, some of the leading sages of the Sanhedrin supported a rebellion led by Simon Bar Kosiba (later known as Bar Kokhba), who established a short-lived independent state that was conquered by the Romans in 135. With this defeat, Jews' hopes that the Temple would be rebuilt were crushed. Nonetheless, belief in a Third Temple remains a cornerstone of Jewish belief.[citation needed]

Romans forbade Jews to enter Jerusalem (except for the day of Tisha B'Av), and forbade any plan to rebuild the Temple. Instead, it took over the Province of Judea directly, renaming it Syria Palaestina, and renaming Jerusalem Aelia Capitolina. Romans did eventually reconstitute the Sanhedrin under the leadership of Judah haNasi (who claimed to be a descendant of King David). They conferred the title of "Nasi" as hereditary, and Judah's sons served both as Patriarch and as heads of the Sanhedrin.[citation needed]

Post-Temple developments

[edit]According to historian Shaye Cohen, by the time three generations had passed after the destruction of the Second Temple, most Jews concluded that the Temple would not be rebuilt during their lives, nor in the foreseeable future. Jews were now confronted with difficult and far-reaching questions:

- How to achieve atonement without the Temple?

- How to explain the disastrous outcome of the rebellion?

- How to live in the post-Temple, Romanized world?

- How to connect present and past traditions?

Regardless of the importance they gave to the Temple, and despite their support of Bar Koseba's revolt, the Pharisees' vision of Jewish law as a means by which ordinary people could engage with the sacred in their daily lives provided them with a position from which to respond to all four challenges in a way meaningful to the vast majority of Jews. Their responses would constitute Rabbinic Judaism.[16]

After the destruction of the Second Temple, these sectarian divisions ended. The Rabbis avoided the term "Pharisee," perhaps because it was a term more often used by non-Pharisees, but also because the term was explicitly sectarian.[citation needed] The Rabbis claimed leadership over all Jews, and added to the Amidah the birkat haMinim, a prayer which in part exclaims, "Praised are You O Lord, who breaks enemies and defeats the wicked," and which is understood as a rejection of sectarians and sectarianism. This shift by no means resolved conflicts over the interpretation of the Torah; rather, it relocated debates between sects to debates within Rabbinic Judaism. The Pharisaic commitment to scholarly debate as a value in and of itself, rather than merely a byproduct of sectarianism, emerged as a defining feature of Rabbinic Judaism.[citation needed]

Thus, as the Pharisees argued that all Israel should act as priests, the Rabbis argued that all Israel should act as rabbis: "The rabbis furthermore want to transform the entire Jewish community into an academy where the whole Torah is studied and kept .... redemption depends on the "rabbinization" of all Israel, that is, upon the attainment of all Jewry of a full and complete embodiment of revelation or Torah, thus achieving a perfect replica of heaven."[54]: 9 Rabbinic Judaism at this time and afterwards contained the idea of the Heavenly Academy, a heavenly institute where God taught scripture.[66]

The Rabbinic era itself is divided into two periods. The first period was that of the Tannaim (from the Aramaic word for "repeat;" the Aramaic root TNY is equivalent to the Hebrew root SNY, which is the basis for "Mishnah." Thus, Tannaim are "Mishnah teachers"), the sages who repeated and thus passed down the Oral Torah. During this period rabbis finalized the canonization of the Tanakh, and in 200 Judah haNasi edited together Tannaitic judgements and traditions into the Mishnah, considered by the rabbis to be the definitive expression of the Oral Torah (although some of the sages mentioned in the Mishnah are Pharisees who lived prior to the destruction of the Second Temple, or prior to the Bar Kozeba Revolt, most of the sages mentioned lived after the revolt).

The second period is that of the Amoraim (from the Aramaic word for "speaker") rabbis and their students who continued to debate legal matters and discuss the meaning of the books of the Bible. In Judea, these discussions occurred at important academies at Tiberias, Caesarea, and Sepphoris. In Babylonia, these discussions largely occurred at important academies that had been established at Nehardea, Pumpeditha and Sura. This tradition of study and debate reached its fullest expression in the development of the Talmudim, elaborations of the Mishnah and records of Rabbinic debates, stories, and judgements, compiled around 400 in Judea and around 500 in Babylon.

Rabbinic Judaism eventually emerged as normative Judaism and in fact many today refer to Rabbinic Judaism simply as "Judaism." Jacob Neusner, however, states that the Amoraim had no ultimate power in their communities. They lived at a time when Jews were subjects of either the Roman or Iranian (Parthian and Persian) empires. These empires left the day-to-day governance in the hands of the Jewish authorities: in Roman Palestine, through the hereditary office of Patriarch (simultaneously the head of the Sanhedrin); in Babylonia, through the hereditary office of the Reish Galuta, the "Head of the Exile" or "Exilarch" (who ratified the appointment of the heads of Rabbinical academies.) According to Professor Neusner:

In Neusner's view, the rabbinic project, as acted out in the Talmud, reflected not the world as it was but the world as rabbis dreamed it should be.

According to S. Baron however, there existed "a general willingness of the people to follow its self imposed Rabbinic rulership". Although the Rabbis lacked authority to impose capital punishment "Flagellation and heavy fines, combined with an extensive system of excommunication were more than enough to uphold the authority of the courts." In fact, the Rabbis took over more and more power from the Reish Galuta until eventually R' Ashi assumed the title Rabbana, heretofore assumed by the exilarch, and appeared together with two other Rabbis as an official delegation "at the gate of King Yazdegard's court." The Amorah (and Tanna) Rav was a personal friend of the last Parthian king Artabenus and Shmuel was close to Shapur I, King of Persia. Thus, the Rabbis had significant means of "coercion" and the people seem to have followed the Rabbinic rulership.[citation needed]

Pharisees and Christianity

[edit]

The Pharisees appear in the New Testament, engaging in conflicts between themselves and John the Baptist[67] and with Jesus, and because Nicodemus the Pharisee (John 3:1) with Joseph of Arimathea entombed Jesus' body at great personal risk. Gamaliel, the highly respected rabbi and, according to Christianity, defender of the apostles, was also a Pharisee, and according to some Christian traditions secretly converted to Christianity.[68]

There are several references in the New Testament to Paul the Apostle being a Pharisee before converting to Christianity,[69] and other members of the Pharisee sect are known from Acts 15:5 to have become Christian believers. It was some members of his group who argued that gentile converts must be circumcised and obliged to follow the Mosaic law, leading to a dispute within the early Church addressed at the Apostolic Council in Jerusalem,[70] in 50 CE.

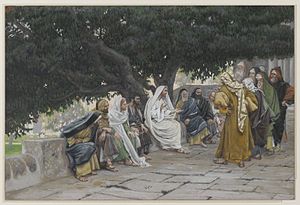

The New Testament, particularly the Synoptic Gospels, presents especially the leadership of the Pharisees as obsessed with man-made rules (especially concerning purity) whereas Jesus is more concerned with God's love; the Pharisees scorn sinners whereas Jesus seeks them out. (The Gospel of John, which is the only gospel where Nicodemus is mentioned, particularly portrays the sect as divided and willing to debate.) Because of the New Testament's frequent depictions of Pharisees as self-righteous rule-followers (see also Woes of the Pharisees and Legalism (theology)), the word "pharisee" (and its derivatives: "pharisaical", etc.) has come into semi-common usage in English to describe a hypocritical and arrogant person who places the letter of the law above its spirit.[71] Jews today typically find this insulting and some consider the use of the word to be anti-Semitic.[72]

Hyam Maccoby speculated that Jesus was himself a Pharisee and that his arguments with Pharisees is a sign of inclusion rather than fundamental conflict (disputation being the dominant narrative mode employed in the Talmud as a search for truth, and not necessarily a sign of opposition).[73] However, Maccoby's views have been widely rejected by scholars.[74]

Examples of passages include the story of Jesus declaring the sins of a paralytic man forgiven and the Pharisees calling the action blasphemy. In the story, Jesus counters the accusation that he does not have the power to forgive sins by pronouncing forgiveness of sins and then healing the man. The account of the Paralytic Man[75] and Jesus's performance of miracles on the Sabbath[76] are often interpreted as oppositional and at times antagonistic to that of the Pharisees' teachings.[77]

However, according to E. P. Sanders, Jesus' actions are actually similar to and consistent with Jewish beliefs and practices of the time, as recorded by the Rabbis, that commonly associate illness with sin and healing with forgiveness. Jews (according to E.P. Sanders) reject the New Testament suggestion that the healing would have been critical of, or criticized by, the Pharisees as no surviving Rabbinic source questions or criticizes this practice,[78] and the notion that Pharisees believed that "God alone" could forgive sins is more of a rhetorical device than historical fact.[79] Another argument from Sanders is that, according to the New Testament, Pharisees wanted to punish Jesus for healing a man's withered hand on Sabbath. Despite the Mishna and Gemara being replete with restrictions on healing on the Sabbath (for example, Mishna Shabbat, 22:6), E.P. Sanders stated that no Rabbinic rule has been found according to which Jesus would have violated Sabbath.[80]

According to Chris Keith, there have been many scholars on both sides who were either highly critical of the historicity of the controversy narratives between Jesus and the scribes and Pharisees or found the stories to be historically credible. Some of the former went as far as to claim that these narratives tried to hide the truth that Jesus in actuality was a Pharisee himself. Keith himself agrees with the latter and agrees that conflicts between Jesus and the literate interpreters of the text happened as the Gospels say and can be traced back to the Historical Jesus, disputing E.P. Sanders in particular. While he acknowledges that the Gospels' stories are a "product of the time(s) in which they were formed" and were affected by later struggles between Christians and Jews, he argues that such symbolism that drapes the Gospel narratives does not mean they are not historical and that there are convincing arguments Jesus did have such debates.[81]

Paula Frederiksen and Michael J. Cook believe that those passages of the New Testament that are seemingly most hostile to the Pharisees were written sometime after the destruction of Herod's Temple in 70 CE.[82][83] Only Christianity and Pharisaism survived the destruction of the Temple, and the two competed for a short time until the Pharisees emerged as the dominant form of Judaism [citation needed]. When many Jews did not convert, Christians sought new converts from among the Gentiles.[84]

Some scholars have found evidence of continuous interactions between Jewish-Christian and rabbinic movements from the mid to late second century to the fourth century.[85][86]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Roth, Cecil (1961). A History of the Jews. Schocken Books. p. 84. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ Sussman, Ayala; Peled, Ruth. "The Dead Sea Scrolls: History & Overview". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ Antiquities of the Jews, 17.42

- ^ Josephus, Flavius. The Antiquities of the Jews, 13.288.

- ^ Ber. 48b; Shab. 14b; Yoma 80a; Yeb. 16a; Nazir 53a; Ḥul. 137b; et al.

- ^ John 3:2

- ^ John 19:38

- ^ Acts 15:5

- ^ "Acts 22:3 Greek Text Analysis". biblehub.com.

- ^ Acts 5:39

- ^ "Acts 23:6 Greek Text Analysis". biblehub.com.

- ^ Philippians 3:5

- ^ Greek word #5330 in Strong's Concordance

- ^ Klein, Ernest (1987). A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the Hebrew Language for Readers of English. University of Haifa. ISBN 965-220-093-X.

- ^ Hebrew word #6567 in Strong's Concordance

- ^ a b c d Cohen, Shaye J.D. (1987). From the Maccabees to the Mishnah. The Westminster Press. ISBN 9780664219116.

- ^ a b Dorot Ha'Rishonim

- ^ Manson, Thomas Walter (1938). "Sadducee and Pharisee". Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 2: 144–159. doi:10.7227/BJRL.22.1.6.

- ^ Finkelstein, Louis (1929). "The Pharisees: Their Origin and Their Philosophy". Harvard Theological Review. 2: 223–231.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Persia". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Ant. 18.1

- ^ Walter Richard (1894). The Gospel According to Peter: A Study. Longmans, Green. p. 9. Retrieved 2022-04-02.

- ^ Neusner, Jacob (12 May 2016). "Jacob Neusner, 'The Rabbinic traditions about the Pharisees before 70'". Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ Coogan, Michael D., ed. (1999). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. p. 350.

- ^ Jeremiah 52:28–30

- ^ See Nehemiah 8:1–18

- ^ Catherwood, Christopher (2011). A Brief History of the Middle East. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-1849018074. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ Levin, Yigal (2020). "The Religion of Idumea and Its Relationship to Early Judaism". Religions. 11 (10): 487. doi:10.3390/rel11100487.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities, 13:5 § 9

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities, 13:10 § 6

- ^ Roth, Cecil A History of the Jews: From Earliest Times Through the Six Day War 1970 ISBN 0-8052-0009-6, p. 84

- ^ Baron, Salo Wittmayer (1956). Schwartz, Leo Walden (ed.). Great Ages and Ideas of the Jewish People. Random House. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud tractate Bava Kamma Ch. 8

- ^ Encyclopaedia Judaica s.v. "Sadducees"

- ^ Ant. 13.288–296.

- ^ Nickelsburg, 93.

- ^ Choi, Junghwa (2013). Jewish Leadership in Roman Palestine from 70 C.E. to 135 C.E. Brill. p. 90. ISBN 978-9004245143. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ Josephus, Jewish War 1:110

- ^ Sievers, 155

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities, 14:3 § 2

- ^ The History of the Second Temple Period, Paolo Sacchi, ch. 8 p. 269: "At this point, the majority of the city's inhabitants, pro-Pharisee and pro-Hyrcanus, decided to open the city's gates to the Romans. Only a small minority of Sadducees took refuge in the Temple and decided to hold out until the very end. This was Autumn 63 BCE. On this occasion Pompey broke into the Temple."

- ^ The Wars of the Jews, Flavius Josephus, Translated by William Whiston, A.M. Auburn and Buffalo John E. Beardsley, 1895, sections 142–150: "And now did many of the priests, even when they saw their enemies assailing them with swords in their hands, without any disturbance, go on with their Divine worship, and were slain while they were offering their drink-offerings, ... The greatest part of them were slain by their own countrymen, of the adverse faction, and an innumerable multitude threw themselves down precipices"

- ^ A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben-Sasson, p. 223: "Thus the independence of Hasmonean Judea came to an end;"

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities, 14:9 § 4; 15:1 § 1; 10 § 4; 11 §§ 5–6

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities, 17:2 § 4; 6 §§ 2–4

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities, 18:1, § 4

- ^ Philip S. Alexander (7 April 1999). Dunn, James D. G. (ed.). Jews and Christians : the parting of the ways, A.D. 70 to 135 : the second Durham-Tübingen Research Symposium on Earliest Christianity and Judaism (Durham, September 1989). W.B. Eerdmans. pp. 1–25. ISBN 0802844987.

- ^ Talmud, Shabbat 31a

- ^ Acts 23.8

- ^ John Hick (Death & Eternal Life, 1994, p. 395) interprets Josephus to be most likely talking about resurrection, while Jason von Ehrenkrook ("The Afterlife in Philo and Josephus", in Heaven, Hell, and the Afterlife: Eternity in Judaism, ed. J. Harold Ellens; vol. 1, pp. 97–118) understands the passage to refer to reincarnation

- ^ Josephus Jewish War 2.8.14; cf. Antiquities 8.14–15.

- ^ Acta 23.6, 26.5.

- ^ Udo Schnelle (2013). Apostle Paul: His Life and Theology. Baker Publishing Group. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-1-4412-4200-6.

- ^ a b c d e Neusner, Jacob Invitation to the Talmud: a Teaching Book (1998)

- ^ Exodus 19:29–24; Deuteronomy 6:7, Deuteronomy 11:19; compare Deuteronomy 31:9; Jeremiah 2:8, Jeremiah 18:18

- ^ Leviticus 11; Deuteronomy 14:3–21

- ^ Deuteronomy 14:1–2, Leviticus 19:28; compare Leviticus 21:5

- ^ Anthony J. Saldarini (2001). Pharisees, Scribes and Sadducees in Palestinian Society: A Sociological Approach. W.B. Eerdmans. pp. 303–. ISBN 978-0-8028-4358-6.

- ^ Rosemary Ruether (1996). Faith and Fratricide: The Theological Roots of Anti-Semitism. Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-0-9653517-5-1.

- ^ Josepheus. The Antiquities of the Jews. pp. 13.5.9.

- ^ Neusner, Jacob (1993). Judaic law from Jesus to the Mishnah : a systematic reply to Professor E.P. Sanders. Scholars Press. pp. 206–207. ISBN 1555408737.

- ^ Neusner, Jacob (1979). From Politics to Piety: the emergence of Pharisaic Judaism. KTAV. pp. 82–90.

- ^ See Zvi Hirsch Chajes The Students Guide through the Talmud Ch. 15 (English edition by Jacob Schacter

- ^ VanderKam, James; Flint, Peter (26 November 2002). The meaning of the Dead Sea scrolls : their significance for understanding the Bible, Judaism, Jesus, and Christianity (1st ed.). HarperSanFrancisco. p. 292. ISBN 006068464X.

- ^ Wise, Michael; Abegg, Martin Jr.; Cook, Edward, eds. (11 October 1996). The Dead Sea scrolls : a new translation (First ed.). HarperCollins. p. 20. ISBN 0060692006.

- ^ Zaleski, Carol (2023-03-04). "heaven". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2023-05-11.

- ^ Matthew 3:1–7, Luke 7:28–30

- ^ Acts 5 merely reads: "33 When they heard this, they were furious and plotted to kill them. 34 Then one in the council stood up, a Pharisee named Gamaliel, a teacher of the law held in respect by all the people, and commanded them to put the apostles outside for a little while. 35 And he said to them: "Men of Israel, take heed to yourselves what you intend to do regarding these men. 36 For some time ago Theudas rose up, claiming to be somebody. A number of men, about four hundred, joined him. He was slain, and all who obeyed him were scattered and came to nothing. 37 After this man, Judas of Galilee rose up in the days of the census, and drew away many people after him. He also perished, and all who obeyed him were dispersed. 38 And now I say to you, keep away from these men and let them alone; for if this plan or this work is of men, it will come to nothing; 39 but if it is of God, you cannot overthrow it—lest you even be found to fight against God."" (New King James Version)

- ^ Apostle Paul as a Pharisee Acts 26:5 See also Acts 23:6, Philippians 3:5

- ^ Acts 15

- ^ "pharisee" The Free Dictionary

- ^ Michael Cook 2008 Modern Jews Engage the New Testament 279

- ^ H. Maccoby, 1986 The Mythmaker. Paul and the Invention of Christianity

- ^ Gregerman, Adam (2012-02-09). "It's 'Kosher' To Accept Real Jesus?". The Forward. Archived from the original on 2016-04-27. Retrieved 2023-03-10.

- ^ Mark 2:1–1

- ^ Mark 3:1–6

- ^ Hooker, Morna D. (1999). The Gospel according to St. Mark (3rd ed.). Hendrickson Publishers. pp. 83–88, 105–108. ISBN 1565630106.

- ^ E.P. Sanders 1993 The Historical Figure of Jesus 213

- ^ Sanders, E. P. (1985). Jesus and Judaism (1st Fortress Press ed.). Fortress Press. p. 273. ISBN 0800620615.

- ^ E.P. Sanders 1993 The Historical Figure of Jesus 215

- ^ Keith, Chris (2020). Jesus against the Scribal Elite: The Origins of the Conflict. T&T Clark. p. 27-28, 187, 190, 191, 197-202. ISBN 978-0567687098.

- ^ Paula Frederiksen, 1988 From Jesus to Christ: The Origins of the New Testament Images of Jesus

- ^ Michael J. Cook, 2008 Modern Jews Engage the New Testament

- ^ e.g., Romans 11:25

- ^ See for instance: Lily C. Vuong, Gender and Purity in the Protevangelium of James, Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2.358 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2013), 210–213; Jonathan Bourgel, "The Holders of the "Word of Truth": The Pharisees in Pseudo-Clementine Recognitions 1.27–71," Journal of Early Christian Studies 25.2 (2017) 171–200.

- ^ Philippe Bobichon, "Autorités religieuses juives et 'sectes' juives dans l'œuvre de Justin Martyr", Revue des Études Augustiniennes 48/1 (2002), pp. 3–22 online; Philippe Bobichon, Dialogue avec Tryphon (Dialogue with Trypho), édition critique, Editions universitaires de Fribourg, 2003, Introduction, pp. 73–108 online

References

[edit]- Baron, Salo W. A Social and Religious History of the Jews Vol 2.

- Boccaccini, Gabriele 2002 Roots of Rabbinic Judaism ISBN 0-8028-4361-1

- Bruce, F.F., The Book of Acts, Revised Edition (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1988)

- Cohen, Shaye J.D. 1988 From the Maccabees to the Mishnah ISBN 0-664-25017-3

- Fredriksen, Paula 1988 From Jesus to Christ ISBN 0-300-04864-5

- Gowler, David B. 1991/2008 Host, Guest, Enemy, and Friend: Portraits of the Pharisees in Luke and Acts (Peter Lang, 1991; ppk, Wipf & Stock, 2008)

- Halevi, Yitzchak Isaac Dorot Ha'Rishonim (Heb.)

- Neusner, Jacob Torah From our Sages: Pirke Avot ISBN 0-940646-05-6

- Neusner, Jacob Invitation to the Talmud: a Teaching Book (1998) ISBN 1-59244-155-6

- Roth, Cecil A History of the Jews: From Earliest Times Through the Six Day War 1970 ISBN 0-8052-0009-6

- Schwartz, Leo, ed. Great Ages and Ideas of the Jewish People ISBN 0-394-60413-X

- Segal, Alan F. Rebecca's Children: Judaism and Christianity in the Roman World, Harvard University Press, 1986, ISBN 0-674-75076-4

- Sacchi, Paolo 2004 The History of the Second Temple Period, London [u.a.] : T & T Clark International, 2004, ISBN 9780567044501

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Sadducees צְדוּקִים | |

|---|---|

| Historical leaders | |

| Founded | 167 BCE |

| Dissolved | 73 CE |

| Headquarters | Jerusalem |

| Ideology | |

| Religion | Hellenistic Judaism |

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

Sadducee, member of a Jewish priestly sect that flourished for about two centuries before the destruction of the Second Temple of Jerusalem in 70 ce. Not much is known of the Sadducees’ origin and early history, but their name may be derived from that of Zadok, who was high priest in the time of Kings David and Solomon. Ezekiel later selected this family as worthy of being entrusted with control of the Temple, and Zadokites formed the Temple hierarchy down to the 2nd century bce.

The Sadducees were the party of high priests, aristocratic families, and merchants—the wealthier elements of the population. They came under the influence of Hellenism, tended to have good relations with the Roman rulers of Palestine, and generally represented the conservative view within Judaism. While their rivals, the Pharisees, claimed the authority of piety and learning, the Sadducees claimed that of birth and social and economic position. During the long period of the two parties’ struggle—which lasted until the Romans’ destruction of Jerusalem in 70 ce—the Sadducees dominated the Temple and its priesthood.

The Sadducees and Pharisees were in constant conflict with each other, not only over numerous details of ritual and the Law but most importantly over the content and extent of God’s revelation to the Jewish people. The Sadducees refused to go beyond the written Torah (first five books of the Bible) and thus, unlike the Pharisees, denied the immortality of the soul, bodily resurrection after death, and—according to the Acts of the Apostles (23:8), the fifth book of the New Testament—the existence of angelic spirits. For the Sadducees, the Oral Law—i.e., the vast body of postbiblical Jewish legal traditions—meant next to nothing. By contrast, the Pharisees revered the Torah but further claimed that oral tradition was part and parcel of Mosaic Law. Because of their strict adherence to the Written Law, the Sadducees acted severely in cases involving the death penalty, and they interpreted literally the Mosaic principle of lex talionis (“an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth”).

Though the Sadducees were conservative in religious matters, their wealth, their haughty bearing, and their willingness to compromise with the Roman rulers aroused the hatred of the common people. As defenders of the status quo, the Sadducees viewed the ministry of Jesus with considerable alarm and apparently played some role in his trial and death. Their lives and political authority were so intimately bound up with Temple worship that after Roman legions destroyed the Temple, the Sadducees ceased to exist as a group, and mention of them quickly disappeared from history.

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

The Sadducees (/ˈsædjəsiːz/; Hebrew: צְדוּקִים, romanized: Ṣəḏūqīm, lit. 'Zadokites') were a sect of Jews active in Judea during the Second Temple period, from the second century BCE to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. The Sadducees are described in contemporary literary sources in contrast to the two other major sects at the time, the Pharisees and the Essenes.

Josephus, writing at the end of the 1st century CE, associates the sect with the upper echelons of Judean society.[1] As a whole, they fulfilled various political, social, and religious roles, including maintaining the Temple in Jerusalem. The group became extinct sometime after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE.

Etymology

[edit]The English term entered via Latin from Koinē Greek: Σαδδουκαῖοι, romanized: Saddukaioi. The name Zadok is related to the root צָדַק, ṣāḏaq (to be right, just),[2] which could be indicative of their aristocratic status in society in the initial period of their existence.[3]

History

[edit]According to Abraham Geiger, the Sadducee sect of Judaism derived their name from that of Zadok, the first High Priest of Israel to serve in Solomon's Temple. The leaders of the sect were proposed as the Kohanim (priests, the "Sons of Zadok", descendants of Eleazar, son of Aaron).[4] The aggadic work Avot of Rabbi Natan tells the story of the two disciples of Antigonus of Sokho (3rd century BCE), Zadok and Boethus. Antigonus having taught the maxim, "Be not like the servants who serve their masters for the sake of the wages, but be rather like those who serve without thought of receiving wages",[5] his students repeated this maxim to their students. Eventually, either the two teachers or their pupils understood this to express the belief that there was neither an afterlife nor a resurrection of the dead, and founded the Sadducee and Boethusian sects. They lived luxuriously, using silver and golden vessels, because (as they claimed) the Pharisees led a hard life on earth and yet would have nothing to show for it in the world to come.[6] The two sects of the Sadducees and Boethusians are thus, in all later Rabbinic sources, always mentioned together, not only as being similar, but as originating at the same time.[7] The use of gold and silver vessels perhaps argues against a priestly association for these groups, as priests at the time would typically use stone vessels, to prevent transmission of impurity.

Josephus mentioned in Antiquities of the Jews that "one Judas, a Gaulonite, of a city whose name was Gamala, who taking with him Sadduc, a Pharisee, became zealous to draw them to a revolt".[8] Paul L. Maier suggests that the sect drew their name from the Sadduc mentioned by Josephus.[9]

The Second Temple period

[edit]

The Second Temple period is the period between the construction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 516 BCE and its destruction by the Romans during the Siege of Jerusalem. Throughout the Second Temple period, Jerusalem saw several shifts in rule. In Achaemenid Judea, the Temple in Jerusalem became the center of worship in Judea. Its priests and attendants appear to have been powerful and influential in secular matters as well, a trend that would continue into the Hellenistic period.

This power and influence also brought accusations of corruption. Alexander's conquest of the Mediterranean world brought an end to Achaemenid control of Jerusalem (539–334/333 BCE) and ushered in the Hellenistic period, which saw the spread of Greek language, culture, and philosophical ideas, which intermixed with Judaism and created Hellenistic Judaism.

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, his generals divided the empire amongst themselves, and for the next 30 years they fought for control of the empire. Judea was first controlled by Ptolemaic Egypt (r. 301–200 BCE) and later by the Seleucid Empire of Syria (r. 200 – 142 BCE). During this period, the High Priest of Israel was generally appointed with the direct approval of the Greek rulership, continuing the intermixing of religious politics with government. King Antiochus IV Epiphanes of the Seleucids began a persecution of traditional Jewish practices around 168–167 BCE, which set off a rebellion in Judea. The most successful rebels were led by the Hasmonean family in what became the Maccabean Revolt, and eventually established the independent Hasmonean kingdom around 142 BCE. While the Sadducees are not attested to this early, many scholars presume that the later sects began to form during the Maccabean era (see Jewish sectarianism below).[10] It is often speculated that the Sadducees grew out of the Judean religious elite in the early Hasmonean period, under rulers such as John Hyrcanus.

Hasmonean rule lasted until 63 BCE, when the Roman general Pompey conquered Jerusalem, at which point the Roman period of Judea began. The province of Roman Judea was created in 6 CE (see also Syria Palaestina). While cooperation between the Romans and the Jews had been strongest during the reigns of Herod and his grandson, Agrippa I, the Romans moved power out of the hands of vassal kings and into the hands of Roman administrators, beginning with the Census of Quirinius in 6 CE. The First Jewish–Roman War broke out in 66 CE. After a few years of conflict, the Romans retook Jerusalem and destroyed the temple, bringing an end to the Second Temple period in 70 CE.[11]

After the Temple destruction

[edit]After the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 CE, the Sadducees appear only in a few references in the Talmud and some Christian texts.[12] In the beginning of Karaite Judaism, the followers of Anan ben David were called "Sadducees" and set a claim of the former being a historical continuity from the latter.[citation needed]

The Sadducee concept of the mortality of the soul is reflected on by Uriel da Costa, who mentions them in his writings.

Role of the Sadducees

[edit]Religious

[edit]The religious responsibilities of the Sadducees included the maintenance of the Temple in Jerusalem. Their high social status was reinforced by their priestly responsibilities, as mandated in the Torah. The priests were responsible for performing sacrifices at the Temple, the primary method of worship in ancient Israel. This included presiding over sacrifices during the three festivals of pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Their religious beliefs and social status were mutually reinforcing, as the priesthood often represented the highest class in Judean society. However, Sadducees and the priests were not completely synonymous. Cohen writes that "not all priests, high priests, and aristocrats were Sadducees; many were Pharisees, and many were not members of any group at all."[13]

Political

[edit]The Sadducees oversaw many formal affairs of the state.[14] Members of the Sadducees:

- Administered the state domestically

- Represented the state internationally

- Participated in the Sanhedrin, and often encountered the Pharisees there.

- Collected taxes. These also came in the form of international tribute from Jews in the Diaspora.

- Equipped and led the army

- Regulated relations with the Roman Empire

- Mediated domestic grievances

Beliefs

[edit]Knowledge about the beliefs of the Sadducees is limited by the fact that not a single line of their own writings has survived out of antiquity, as the destruction of Jerusalem and much of the Judean elite in 70 CE seems to have broken them. Extant writings on the Sadducees are often from sources hostile to them; Josephus was a rival Pharisee, Christian records were generally not sympathetic, and the rabbinic tradition (descended from the Pharisees) is uniformly hostile.[15]

General

[edit]The Sadducees rejected the Oral Torah as proposed by the Pharisees. Rather, they saw the Written Torah as the sole source of divine authority.[16] Later writings of the Pharisees criticized this belief as one that strengthened the Sadducees' own power.

According to Josephus, the Sadducees beliefs included:

- Rejection of the idea of fate or a pre-ordained future.

- God does not commit or even think evil.

- Man has free will; "man has the free choice of good or evil".

- The soul is not immortal and there is no afterlife, and no rewards or penalties after death.

- It is a virtue to debate and dispute with philosophy teachers.[15][17]

The Sadducees did not believe in resurrection of the dead, but believed (contrary to the claim of Josephus) in the traditional Jewish concept of Sheol for those who had died.[18] Josephus also includes a claim that the Sadducees are rude compared to loving and compassionate Pharisees, but this is generally considered more of a sectarian insult rather than an unbiased judgment of the Sadducees on their own terms.[15] Similarly, Josephus brags that the Sadducees were often forced to back down if their judgments clashed with the Pharisees, as he says that the Pharisees were more popular with the multitude.[15]

The Sadducees occasionally show up in the Christian gospels, but without much detail: usually merely as parts of a list of opponents of Jesus. The Christian Acts of the Apostles contains somewhat more information:[15]

- The Sadducees were associated with the party of the high priest of the era, and seem to have had a majority of the Sanhedrin, if not all (Gamaliel is a Pharisee member).[19]

- The Sadducees did not believe in resurrection, whereas the Pharisees did. In Acts, Paul of Tarsus chose this point of division to attempt to gain the protection of the Pharisees (around 59 CE).[20]

- The Sadducees rejected the notion of spirits or angels, whereas the Pharisees acknowledged them.[20]

Disputes with the Pharisees

[edit]- According to the Sadducees, spilt water becomes ritually impure through its pouring. The Pharisees denied that this was sufficient grounds for impurity in Mishnah Yadaim 4:7. Many Pharisee–Sadducee disputes revolved around issues of ritual purity.

- According to the Jewish laws of inheritance, the property of a deceased man is inherited by his sons. If the man had only daughters, his property would be inherited by his daughters upon his death, according to Numbers 27:8. The Sadducees, however, whenever dividing the inheritance among the relatives of the deceased, such as when the deceased left no issue, would perfunctorily seek familial ties so that the near of kin to the deceased and who inherits his property could, hypothetically, be his paternal aunt. The Sadducees would justify their practice by a fortiori, an inference from minor to major premise, saying: "If the daughter of his son's son can inherit him (i.e., such as when her father left no male issue), is it not then fitting that his own daughter inherit him?!" (i.e., who is more closely related to him than his great-granddaughter), according to the Jerusalem Talmud (Baba Bathra 21b). The early Jewish sage Yohanan ben Zakkai tore down their argument, saying that the only reason the daughter was empowered to inherit her father was because her father left no male issue. However, a man's daughter – where there are sons, has no power to inherit her father's estate. Moreover, a deceased man who leaves no issue always has a distant male relative to whom his estate can be given. The Sadducees eventually agreed with the Pharisaic teaching. The vindication of Yohanan ben Zakkai and the Pharisees over the Sadducees gave rise to this date being held in honor in the Megillat Taanit according to the Rashbam in the Babylonian Talmud, Baba Bathra 115b–116a); Jerusalem Talmud (Baba Bathra 8:1 [21b–22a])

- The Sadducees demanded that a master pay for damages caused by his slave. The Pharisees imposed no such obligation, viewing that a slave could intentionally cause damage to see the liability for it brought on his master in Mishnah Yadaim 4:7

- The Pharisees posited that false witnesses should be executed if the verdict was pronounced based on their testimony—even if not yet carried out. The Sadducees argued that false witnesses should be executed only if the death penalty had already been carried out on the falsely accused in Mishnah Makot 1.6.

Later rabbinic literature took a dim view of both the Sadducees and Boethusians, not only due to their perceived carefree approach to keeping to the Torah and the Oral Torah but also due to their attempts to persuade the common folk to join their ranks according to Sifri to Deuteronomy (p. 233, Torah Ve'Hamitzvah edition).[verification needed] Maimonides viewed the Sadducees as rejecting the Oral Torah as an excuse to interpret the Written Torah in a lenient, personally convenient manner in his commentary to Pirkei Avot, 1.3.1 1:3. He described the Sadducees as "harming Israel and causing the nation to stray from following God" in the Mishneh Torah, Hilchoth Avodah Zarah 10:2.

Jewish sectarianism

[edit]

The Jewish community of the Second Temple period is often defined by its sectarian and fragmented attributes. Josephus, in Antiquities, contextualizes the Sadducees as opposed to the Pharisees and the Essenes. The Sadducees are also notably distinguishable from the growing Jesus movement, which later evolved into Christianity. These groups differed in their beliefs, social statuses, and sacred texts. Though the Sadducees produced no primary works themselves, their attributes can be derived from other contemporaneous texts, including the New Testament, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and later, the Mishnah and Talmud. Overall, the Sadducees represented an aristocratic, wealthy, and traditional elite within the hierarchy.

Opposition to the Essenes

[edit]The Dead Sea Scrolls, which are often attributed to the Essenes, suggest clashing ideologies and social positions between the Essenes and the Sadducees. In fact, some scholars suggest that the Essenes originated as a sect of Zadokites, which would indicate that the group itself had priestly, and thus Sadducaic origins. Within the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Sadducees are often referred to as Manasseh. The scrolls suggest that the Sadducees (Manasseh) and the Pharisees (Ephraim) became religious communities that were distinct from the Essenes, the true Judah. Clashes between the Essenes and the Sadducees are depicted in the Pesher on Nahum, which states "They [Manasseh] are the wicked ones ... whose reign over Israel will be brought down ... his wives, his children, and his infant will go into captivity. His warriors and his honored ones [will perish] by the sword."[21] The reference to the Sadducees as those who reign over Israel corroborates their aristocratic status as opposed to the more fringe group of Essenes. Furthermore, it suggests that the Essenes challenged the authenticity of the rule of the Sadducees, blaming the downfall of ancient Israel and the siege of Jerusalem on their impiety. The Dead Sea Scrolls specify the Sadducaic elite as those who broke the covenant with God in their rule of the Judean state, and thus became targets of divine vengeance.

Opposition to the early Christian church

[edit]The New Testament, specifically the books of Mark and Matthew, describe anecdotes which hint at hostility between Jesus and the Sadducaic establishment. A pericope in Mark 12 and Matthew 22 recounts a dispute between Jesus and a Sadducee who challenged the resurrection of the dead by asking who the husband of a resurrected woman would be who had been married to each of seven brothers at one point. Jesus responds by saying that the resurrected "neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like angels in heaven." He also insults them on their own terms as knowing neither the scriptures nor the power of God, presumably a claim that even though the Sadducee insisted on the written law, Jesus considered them to have gotten it wrong.[22][23]