888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

The age-long conflict between the Sadducees and the Pharisees was the most important factor in the development of Judaism. The Pharisees were the champions of the oral Law, which at first was quite independent of the written Torah and was deeply entrenched in old popular custom and usage. On the other hand, the Sadducees mainly represented the old conservative positions of the priesthood and inherited the tradition of the older scribism.

The "scribe," as he is depicted in Sirach (c. 190 BCC), is a judge and man of affairs, a cultivated student of "wisdom," well acquainted, of course, with the contents of the written Law, and a frequenter of the courts of kings. He belongs to the leisured, aristocratic class and is poles asunder from the typical Pharisee and teacher of the Law, who was drawn from the ranks of the people. It was in the reaction against Hellenism that Torah-study (study of the Law) was born.

The public reading and exposition of the Torah in the synagogue probably dates only from the Maccabean period. Both parties were compelled to devote themselves to Torah-study, in the new and exacting way demanded by the times, the Sadducees, because, in their view, the Law was the only valid standard for fixing juristic and religious practice, and the Pharisees, because it was necessary for them to adjust their oral tradition, as far as possible, to the written word.

The first result of Pharisaic activity in this direction was the development of a remarkably rich and subtle exegesis. A further result was the evolution of new laws by exegetical methods.

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

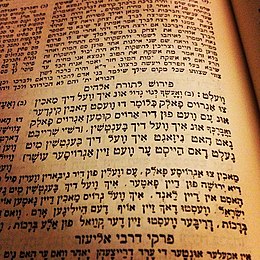

The Torah (/ˈtɔːrə/ or /ˈtoʊrə/;[1] Biblical Hebrew: תּוֹרָה Tōrā, "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy.[2] In Christianity, the Torah is also known as the Pentateuch (/ˈpɛntətjuːk/) or the Five Books of Moses. In Rabbinical Jewish tradition it is also known as the Written Torah (תּוֹרָה שֶׁבִּכְתָב, Tōrā šebbīḵṯāv). If meant for liturgic purposes, it takes the form of a Torah scroll (Hebrew: ספר תורה Sefer Torah). If in bound book form, it is called Chumash, and is usually printed with the rabbinic commentaries (perushim).

In rabbinic literature, the word Torah denotes both the five books (תורה שבכתב "Torah that is written") and the Oral Torah (תורה שבעל פה, "Torah that is spoken"). It has also been used, however, to designate the entire Hebrew Bible. The Oral Torah consists of interpretations and amplifications which according to rabbinic tradition have been handed down from generation to generation and are now embodied in the Talmud and Midrash.[3] Rabbinic tradition's understanding is that all of the teachings found in the Torah (both written and oral) were given by God through the prophet Moses, some at Mount Sinai and others at the Tabernacle, and all the teachings were written down by Moses, which resulted in the Torah that exists today. According to the Midrash, the Torah was created prior to the creation of the world, and was used as the blueprint for Creation.[4] Though hotly debated, the general trend in biblical scholarship is to recognize the final form of the Torah as a literary and ideological unity, based on earlier sources, largely complete by the Persian period,[5][6][7] with possibly some later additions during the Hellenistic period.[8][9]

The words of the Torah are written on a scroll by a scribe (sofer) in Hebrew. A Torah portion is read every Monday morning and Thursday morning at a shul (synagogue) but only if there are ten males above the age of thirteen. Reading the Torah publicly is one of the bases of Jewish communal life. The Torah is also considered a sacred book outside Judaism; in Samaritanism, the Samaritan Pentateuch is a text of the Torah written in the Samaritan script and used as sacred scripture by the Samaritans; the Torah is also common among all the different versions of the Christian Old Testament; in Islam, the Tawrat (Arabic: توراة) is the Arabic name for the Torah within its context as an Islamic holy book believed by Muslims to have been given by God to the prophets and messengers amongst the Children of Israel.[10]

Meaning and names

[edit]The word "Torah" in Hebrew is derived from the root ירה, which in the hif'il conjugation means 'to guide' or 'to teach'.[11] The meaning of the word is therefore "teaching", "doctrine", or "instruction"; the commonly accepted "law" gives a wrong impression.[12] The Alexandrian Jews who translated the Septuagint used the Greek word nomos, meaning norm, standard, doctrine, and later "law". Greek and Latin Bibles then began the custom of calling the Pentateuch (five books of Moses) The Law. Other translational contexts in the English language include custom, theory, guidance,[3] or system.[13]

The term "Torah" is used in the general sense to include both Rabbinic Judaism's written and oral law, serving to encompass the entire spectrum of authoritative Jewish religious teachings throughout history, including the Oral Torah which comprises the Mishnah, the Talmud, the Midrash and more. The inaccurate rendering of "Torah" as "Law"[14] may be an obstacle to understanding the ideal that is summed up in the term talmud torah (תלמוד תורה, "study of Torah").[3] The term "Torah" is also used to designate the entire Hebrew Bible.[15]

The earliest name for the first part of the Bible seems to have been "The Torah of Moses". This title, however, is found neither in the Torah itself, nor in the works of the pre-Exilic literary prophets. It appears in Joshua[16] and Kings,[17] but it cannot be said to refer there to the entire corpus (according to academic Bible criticism). In contrast, there is every likelihood that its use in the post-Exilic works[18] was intended to be comprehensive. Other early titles were "The Book of Moses"[19] and "The Book of the Torah",[20] which seems to be a contraction of a fuller name, "The Book of the Torah of God".[21][22]

Alternative names

[edit]Christian scholars usually refer to the first five books of the Hebrew Bible as the 'Pentateuch' (/ˈpɛn.təˌtjuːk/, PEN-tə-tewk; ‹See Tfd›Greek: πεντάτευχος, pentáteukhos, 'five scrolls'), a term first used in the Hellenistic Judaism of Alexandria.[23]

The "Tawrat" (also Tawrah or Taurat; Arabic: توراة) is the Arabic name for the Torah, which Muslims believe is an Islamic holy book given by God to the prophets and messengers amongst the Children of Israel.[10]

Contents

[edit]

The Torah starts with God creating the world, then describes the beginnings of the people of Israel, their descent into Egypt, and the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai. It ends with the death of Moses, just before the people of Israel cross to the Promised Land of Canaan. Interspersed in the narrative are the specific teachings (religious obligations and civil laws) given explicitly (i.e. Ten Commandments) or implicitly embedded in the narrative (as in Exodus 12 and 13 laws of the celebration of Passover).

In Hebrew, the five books of the Torah are identified by the incipits in each book;[24] and the common English names for the books are derived from the Greek Septuagint[citation needed] and reflect the essential theme of each book:

- Bəreshit (בְּרֵאשִׁית, literally "In the beginning")—Genesis, from Γένεσις (Génesis, "Creation")

- Shəmot (שְׁמוֹת, literally "Names")—Exodus, from Ἔξοδος (Éxodos, "Exit")

- Vayikra (וַיִּקְרָא, literally "And He called")—Leviticus, from Λευιτικόν (Leuitikón, "Relating to the Levites")

- Bəmidbar (בְּמִדְבַּר, literally "In the desert [of]")—Numbers, from Ἀριθμοί (Arithmoí, "Numbers")

- Dəvarim (דְּבָרִים, literally "Things" or "Words")—Deuteronomy, from Δευτερονόμιον (Deuteronómion, "Second-Law")

Genesis

[edit]The Book of Genesis is the first book of the Torah.[25] It is divisible into two parts, the Primeval history (chapters 1–11) and the Ancestral history (chapters 12–50).[26] The primeval history sets out the author's (or authors') concepts of the nature of the deity and of humankind's relationship with its maker: God creates a world which is good and fit for mankind, but when man corrupts it with sin God decides to destroy his creation, using the flood, saving only the righteous Noah and his immediate family to reestablish the relationship between man and God.[27] The Ancestral history (chapters 12–50) tells of the prehistory of Israel, God's chosen people.[28] At God's command Noah's descendant Abraham journeys from his home into the God-given land of Canaan, where he dwells as a sojourner, as does his son Isaac and his grandson Jacob. Jacob's name is changed to Israel, and through the agency of his son Joseph, the children of Israel descend into Egypt, 70 people in all with their households, and God promises them a future of greatness. Genesis ends with Israel in Egypt, ready for the coming of Moses and the Exodus. The narrative is punctuated by a series of covenants with God, successively narrowing in scope from all mankind (the covenant with Noah) to a special relationship with one people alone (Abraham and his descendants through Isaac and Jacob).[29]

Exodus

[edit]The Book of Exodus is the second book of the Torah, immediately following Genesis. The book tells how the ancient Israelites leave slavery in Egypt through the strength of Yahweh, the God who has chosen Israel as his people. Yahweh inflicts horrific harm on their captors via the legendary Plagues of Egypt. With the prophet Moses as their leader, they journey through the wilderness to Mount Sinai, where Yahweh promises them the land of Canaan (the "Promised Land") in return for their faithfulness. Israel enters into a covenant with Yahweh who gives them their laws and instructions to build the Tabernacle, the means by which he will come from heaven and dwell with them and lead them in a holy war to possess the land, and then give them peace.

Traditionally ascribed to Moses himself, modern scholarship sees the book as initially a product of the Babylonian exile (6th century BCE), from earlier written and oral traditions, with final revisions in the Persian post-exilic period (5th century BCE).[30][31] Carol Meyers, in her commentary on Exodus suggests that it is arguably the most important book in the Bible, as it presents the defining features of Israel's identity: memories of a past marked by hardship and escape, a binding covenant with God, who chooses Israel, and the establishment of the life of the community and the guidelines for sustaining it.[32]

Leviticus

[edit]The Book of Leviticus begins with instructions to the Israelites on how to use the Tabernacle, which they had just built (Leviticus 1–10). This is followed by rules of clean and unclean (Leviticus 11–15), which includes the laws of slaughter and animals permissible to eat (see also: Kashrut), the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 16), and various moral and ritual laws sometimes called the Holiness Code (Leviticus 17–26). Leviticus 26 provides a detailed list of rewards for following God's commandments and a detailed list of punishments for not following them. Leviticus 17 establishes sacrifices at the Tabernacle as an everlasting ordinance, but this ordinance is altered in later books with the Temple being the only place in which sacrifices are allowed.[citation needed]

Numbers

[edit]

The Book of Numbers is the fourth book of the Torah.[33] The book has a long and complex history, but its final form is probably due to a Priestly redaction (i.e., editing) of a Yahwistic source made some time in the early Persian period (5th century BCE).[6] The name of the book comes from the two censuses taken of the Israelites.

Numbers begins at Mount Sinai, where the Israelites have received their laws and covenant from God and God has taken up residence among them in the sanctuary.[34] The task before them is to take possession of the Promised Land. The people are counted and preparations are made for resuming their march. The Israelites begin the journey, but they "murmur" at the hardships along the way, and about the authority of Moses and Aaron. For these acts, God destroys approximately 15,000 of them through various means. They arrive at the borders of Canaan and send spies into the land. Upon hearing the spies' fearful report concerning the conditions in Canaan, the Israelites refuse to take possession of it. God condemns them to death in the wilderness until a new generation can grow up and carry out the task. The book ends with the new generation of Israelites in the "plains of Moab" ready for the crossing of the Jordan River.[35]

Numbers is the culmination of the story of Israel's exodus from oppression in Egypt and their journey to take possession of the land God promised their fathers. As such it draws to a conclusion the themes introduced in Genesis and played out in Exodus and Leviticus: God has promised the Israelites that they shall become a great (i.e. numerous) nation, that they will have a special relationship with Yahweh their god, and that they shall take possession of the land of Canaan. Numbers also demonstrates the importance of holiness, faithfulness and trust: despite God's presence and his priests, Israel lacks faith and the possession of the land is left to a new generation.[6]

Deuteronomy

[edit]The Book of Deuteronomy is the fifth book of the Torah. Chapters 1–30 of the book consist of three sermons or speeches delivered to the Israelites by Moses on the plains of Moab, shortly before they enter the Promised Land. The first sermon recounts the forty years of wilderness wanderings which had led to that moment, and ends with an exhortation to observe the law (or teachings), later referred to as the Law of Moses; the second reminds the Israelites of the need to follow Yahweh and the laws (or teachings) he has given them, on which their possession of the land depends; and the third offers the comfort that even should Israel prove unfaithful and so lose the land, with repentance all can be restored.[36] The final four chapters (31–34) contain the Song of Moses, the Blessing of Moses, and narratives recounting the passing of the mantle of leadership from Moses to Joshua and, finally, the death of Moses on Mount Nebo.

Presented as the words of Moses delivered before the conquest of Canaan, a broad consensus of modern scholars see its origin in traditions from Israel (the northern kingdom) brought south to the Kingdom of Judah in the wake of the Assyrian conquest of Aram (8th century BCE) and then adapted to a program of nationalist reform in the time of Josiah (late 7th century BCE), with the final form of the modern book emerging in the milieu of the return from the Babylonian captivity during the late 6th century BCE.[37] Many scholars see the book as reflecting the economic needs and social status of the Levite caste, who are believed to have provided its authors;[38] those likely authors are collectively referred to as the Deuteronomist.

One of its most significant verses is Deuteronomy 6:4,[39] the Shema Yisrael, which has become the definitive statement of Jewish identity: "Hear, O Israel: the LORD our God, the LORD is one." Verses 6:4–5 were also quoted by Jesus in Mark 12:28–34[40] as part of the Great Commandment.

Composition

[edit]The Talmud states that the Torah was written by Moses, with the exception of the last eight verses of Deuteronomy, describing his death and burial, being written by Joshua.[41] According to the Mishnah one of the essential tenets of Judaism is that God transmitted the text of the Torah to Moses[42] over the span of the 40 years the Israelites were in the desert[43] and Moses was like a scribe who was dictated to and wrote down all of the events, the stories and the commandments.[44]

According to Jewish tradition, the Torah was recompiled by Ezra during Second Temple period.[45][46] The Talmud says that Ezra changed the script used to write the Torah from the older Hebrew script to Assyrian script, so called according to the Talmud, because they brought it with them from Assyria.[47] Maharsha says that Ezra made no changes to the actual text of the Torah based on the Torah's prohibition of making any additions or deletions to the Torah in Deuteronomy 12:32. [48]

By contrast, the modern scholarly consensus rejects Mosaic authorship, and affirms that the Torah has multiple authors and that its composition took place over centuries.[6] The precise process by which the Torah was composed, the number of authors involved, and the date of each author are hotly contested. Throughout most of the 20th century, there was a scholarly consensus surrounding the documentary hypothesis, which posits four independent sources, which were later compiled together by a redactor: J, the Jahwist source, E, the Elohist source, P, the Priestly source, and D, the Deuteronomist source. The earliest of these sources, J, would have been composed in the late 7th or the 6th century BCE, with the latest source, P, being composed around the 5th century BCE.

The consensus around the documentary hypothesis collapsed in the last decades of the 20th century.[49] The groundwork was laid with the investigation of the origins of the written sources in oral compositions, implying that the creators of J and E were collectors and editors and not authors and historians.[50] Rolf Rendtorff, building on this insight, argued that the basis of the Pentateuch lay in short, independent narratives, gradually formed into larger units and brought together in two editorial phases, the first Deuteronomic, the second Priestly.[51] By contrast, John Van Seters advocates a supplementary hypothesis, which posits that the Torah was derived from a series of direct additions to an existing corpus of work.[52] A "neo-documentarian" hypothesis, which responds to the criticism of the original hypothesis and updates the methodology used to determine which text comes from which sources, has been advocated by biblical historian Joel S. Baden, among others.[53][54] Such a hypothesis continues to have adherents in Israel and North America.[54]

The majority of scholars today continue to recognize Deuteronomy as a source, with its origin in the law-code produced at the court of Josiah as described by De Wette, subsequently given a frame during the exile (the speeches and descriptions at the front and back of the code) to identify it as the words of Moses.[55] However, since the 1990s, the biblical description of Josiah's reforms (including his court's production of a law-code) have become heavily debated among academics.[56][57][58] Most scholars also agree that some form of Priestly source existed, although its extent, especially its end-point, is uncertain.[59] The remainder is called collectively non-Priestly, a grouping which includes both pre-Priestly and post-Priestly material.[60]

Date of compilation

[edit]The final Torah is widely seen as a product of the Persian period (539–332 BCE, probably 450–350 BCE).[61] This consensus echoes a traditional Jewish view which gives Ezra, the leader of the Jewish community on its return from Babylon, a pivotal role in its promulgation.[62] Many theories have been advanced to explain the composition of the Torah, but two have been especially influential.[63] The first of these, Persian Imperial authorisation, advanced by Peter Frei in 1985, holds that the Persian authorities required the Jews of Jerusalem to present a single body of law as the price of local autonomy.[64] Frei's theory was, according to Eskenazi, "systematically dismantled" at an interdisciplinary symposium held in 2000, but the relationship between the Persian authorities and Jerusalem remains a crucial question.[65] The second theory, associated with Joel P. Weinberg and called the "Citizen-Temple Community", proposes that the Exodus story was composed to serve the needs of a post-exilic Jewish community organised around the Temple, which acted in effect as a bank for those who belonged to it.[66]

A minority of scholars would place the final formation of the Pentateuch somewhat later, in the Hellenistic (332–164 BCE) or even Hasmonean (140–37 BCE) periods.[67] Russell Gmirkin, for instance, argues for a Hellenistic dating on the basis that the Elephantine papyri, the records of a Jewish colony in Egypt dating from the last quarter of the 5th century BCE, make no reference to a written Torah, the Exodus, or to any other biblical event, though it does mention the festival of Passover.[68]

Adoption of Torah law

[edit]

In his seminal Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels, Julius Wellhausen argued that Judaism as a religion based on widespread observance of the Torah and its laws first emerged in 444 BCE when, according to the biblical account provided in the Book of Nehemiah (chapter 8), a priestly scribe named Ezra read a copy of the Mosaic Torah before the populace of Judea assembled in a central Jerusalem square.[69] Wellhausen believed that this narrative should be accepted as historical because it sounds plausible, noting: "The credibility of the narrative appears on the face of it."[70] Following Wellhausen, most scholars throughout the 20th and early 21st centuries[like whom?] have accepted that widespread Torah observance began sometime around the middle of the 5th century BCE.[clarify][citation needed]

More recently, Yonatan Adler has argued that in fact there is no surviving evidence to support the notion that the Torah was widely known, regarded as authoritative, and put into practice prior to the middle of the 2nd century BCE.[71] Adler explored the likelihhood that Judaism, as the widespread practice of Torah law by Jewish society at large, first emerged in Judea during the reign of the Hasmonean dynasty, centuries after the putative time of Ezra.[72] By contrast, John J. Collins has argued that the observance of the Torah started in Persian Yehud when the Judeans who returned from exile understood its normativity as the observance of selected, ancestral laws of high symbolic value, while during the Maccabean revolt Jews started a much more detailed observance of its precepts.[73]

Significance in Judaism

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

Traditional views on authorship

[edit]Rabbinic writings state that the Oral Torah was given to Moses at Mount Sinai, which, according to the tradition of Orthodox Judaism, occurred in 1312 BCE. The Orthodox rabbinic tradition holds that the Written Torah was recorded during the following forty years,[74] though many non-Orthodox Jewish scholars affirm the modern scholarly consensus that the Written Torah has multiple authors and was written over centuries.[75]

All classical rabbinic views hold that the Torah was entirely Mosaic and of divine origin.[76] Present-day Reform and Liberal Jewish movements all reject Mosaic authorship, as do most shades of Conservative Judaism.[77]

Ritual use

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

Torah reading (Hebrew: קריאת התורה, K'riat HaTorah, "Reading [of] the Torah") is a Jewish religious ritual that involves the public reading of a set of passages from a Torah scroll. The term often refers to the entire ceremony of removing the Torah scroll (or scrolls) from the ark, chanting the appropriate excerpt with traditional cantillation, and returning the scroll(s) to the ark. It is distinct from academic Torah study.

Regular public reading of the Torah was introduced by Ezra the Scribe after the return of the Jewish people from the Babylonian captivity (c. 537 BCE), as described in the Book of Nehemiah.[78] In the modern era, adherents of Orthodox Judaism practice Torah-reading according to a set procedure they believe has remained unchanged in the two thousand years since the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem (70 CE). In the 19th and 20th centuries CE, new movements such as Reform Judaism and Conservative Judaism have made adaptations to the practice of Torah reading, but the basic pattern of Torah reading has usually remained the same:

As a part of the morning prayer services on certain days of the week, fast days, and holidays, as well as part of the afternoon prayer services of Shabbat, Yom Kippur, a section of the Pentateuch is read from a Torah scroll. On Shabbat (Saturday) mornings, a weekly section ("parashah") is read, selected so that the entire Pentateuch is read consecutively each year. The division of parashot found in the modern-day Torah scrolls of all Jewish communities (Ashkenazic, Sephardic, and Yemenite) is based upon the systematic list provided by Maimonides in Mishneh Torah, Laws of Tefillin, Mezuzah and Torah Scrolls, chapter 8. Maimonides based his division of the parashot for the Torah on the Aleppo Codex. Conservative and Reform synagogues may read parashot on a triennial rather than annual schedule,[79][80] On Saturday afternoons, Mondays, and Thursdays, the beginning of the following Saturday's portion is read. On Jewish holidays, the beginnings of each month, and fast days, special sections connected to the day are read.

Jews observe an annual holiday, Simchat Torah, to celebrate the completion and new start of the year's cycle of readings.

Torah scrolls are often dressed with a sash, a special Torah cover, various ornaments, and a keter (crown), although such customs vary among synagogues. Congregants traditionally stand in respect when the Torah is brought out of the ark to be read, while it is being carried, and lifted, and likewise while it is returned to the ark, although they may sit during the reading itself.

Biblical law

[edit]The Torah contains narratives, statements of law, and statements of ethics. Collectively these laws, usually called biblical law or commandments, are sometimes referred to as the Law of Moses (Torat Moshɛ תּוֹרַת־מֹשֶׁה), Mosaic Law, or Sinaitic Law.

The Oral Torah

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

Rabbinic tradition holds that Moses learned the whole Torah while he lived on Mount Sinai for 40 days and nights and both the Oral and the written Torah were transmitted in parallel with each other. Where the Torah leaves words and concepts undefined, and mentions procedures without explanation or instructions, the reader is required to seek out the missing details from supplemental sources known as the Oral Law or Oral Torah.[81] Some of the Torah's most prominent commandments needing further explanation are:

- Tefillin: As indicated in Deuteronomy 6:8 among other places, tefillin are to be placed on the arm and on the head between the eyes. However, there are no details provided regarding what tefillin are or how they are to be constructed.

- Kashrut: As indicated in Exodus 23:19 among other places, a young goat may not be boiled in its mother's milk. In addition to numerous other problems with understanding the ambiguous nature of this law, there are no vowelization characters in the Torah; they are provided by the oral tradition. This is particularly relevant to this law, as the Hebrew word for milk (חלב) is identical to the word for animal fat when vowels are absent. Without the oral tradition, it is not known whether the violation is in mixing meat with milk or with fat.

- Shabbat laws: With the severity of Sabbath violation, namely the death penalty, one would assume that direction would be provided as to how exactly such a serious and core commandment should be upheld. However, most information regarding the rules and traditions of Shabbat are dictated in the Talmud and other books deriving from Jewish oral law.

According to classical rabbinic texts this parallel set of material was originally transmitted to Moses at Sinai, and then from Moses to Israel. At that time it was forbidden to write and publish the oral law, as any writing would be incomplete and subject to misinterpretation and abuse.[82]

However, after exile, dispersion, and persecution, this tradition was lifted when it became apparent that in writing was the only way to ensure that the Oral Law could be preserved. After many years of effort by a great number of tannaim, the oral tradition was written down around 200 CE by Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi, who took up the compilation of a nominally written version of the Oral Law, the Mishnah (משנה). Other oral traditions from the same time period not entered into the Mishnah were recorded as Baraitot (external teaching), and the Tosefta. Other traditions were written down as Midrashim.

After continued persecution more of the Oral Law was committed to writing. A great many more lessons, lectures and traditions only alluded to in the few hundred pages of Mishnah, became the thousands of pages now called the Gemara. Gemara is written in Aramaic (specifically Jewish Babylonian Aramaic), having been compiled in Babylon. The Mishnah and Gemara together are called the Talmud. The rabbis in the Land of Israel also collected their traditions and compiled them into the Jerusalem Talmud. Since the greater number of rabbis lived in Babylon, the Babylonian Talmud has precedence should the two be in conflict.

Orthodox and Conservative branches of Judaism accept these texts as the basis for all subsequent halakha and codes of Jewish law, which are held to be normative. Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism deny that these texts, or the Torah itself for that matter, may be used for determining normative law (laws accepted as binding) but accept them as the authentic and only Jewish version for understanding the Torah and its development throughout history.[citation needed] Humanistic Judaism holds that the Torah is a historical, political, and sociological text, but does not believe that every word of the Torah is true, or even morally correct. Humanistic Judaism is willing to question the Torah and to disagree with it, believing that the entire Jewish experience, not just the Torah, should be the source for Jewish behavior and ethics.[83]

Divine significance of letters, Jewish mysticism

[edit]

Kabbalists hold that not only do the words of Torah give a divine message, but they also indicate a far greater message that extends beyond them. Thus they hold that even as small a mark as a kotso shel yod (קוצו של יוד), the serif of the Hebrew letter yod (י), the smallest letter, or decorative markings, or repeated words, were put there by God to teach scores of lessons. This is regardless of whether that yod appears in the phrase "I am the LORD thy God" (אָנֹכִי יְהוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ, Exodus 20:2) or whether it appears in "And God spoke unto Moses saying" (וַיְדַבֵּר אֱלֹהִים, אֶל-מֹשֶׁה; וַיֹּאמֶר אֵלָיו, אֲנִי יְהוָה. Exodus 6:2). In a similar vein, Rabbi Akiva (c. 50 – c. 135 CE), is said to have learned a new law from every et (את) in the Torah (Talmud, tractate Pesachim 22b); the particle et is meaningless by itself, and serves only to mark the direct object. In other words, the Orthodox belief is that even apparently contextual text such as "And God spoke unto Moses saying ..." is no less holy and sacred than the actual statement.[citation needed]

Production and use of a Torah scroll

[edit]

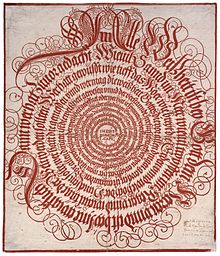

Manuscript Torah scrolls are still scribed and used for ritual purposes (i.e., religious services); this is called a Sefer Torah ("Book [of] Torah"). They are written using a painstakingly careful method by highly qualified scribes. It is believed that every word, or marking, has divine meaning and that not one part may be inadvertently changed lest it lead to error. The fidelity of the Hebrew text of the Tanakh, and the Torah in particular, is considered paramount, down to the last letter: translations or transcriptions are frowned upon for formal service use, and transcribing is done with painstaking care. An error of a single letter, ornamentation, or symbol of the 304,805 stylized letters that make up the Hebrew Torah text renders a Torah scroll unfit for use, hence a special skill is required and a scroll takes considerable time to write and check.

According to Jewish law, a sefer Torah (plural: Sifrei Torah) is a copy of the formal Hebrew text handwritten on gevil or klaf (forms of parchment) by using a quill (or other permitted writing utensil) dipped in ink. Written entirely in Hebrew, a sefer Torah contains 304,805 letters, all of which must be duplicated precisely by a trained sofer ("scribe"), an effort that may take as long as approximately one and a half years. Most modern Sifrei Torah are written with forty-two lines of text per column (Yemenite Jews use fifty), and very strict rules about the position and appearance of the Hebrew letters are observed. See for example the Mishnah Berurah on the subject.[84] Any of several Hebrew scripts may be used, most of which are fairly ornate and exacting.

The completion of the Sefer Torah is a cause for great celebration, and it is a mitzvah for every Jew to either write or have written for him a Sefer Torah. Torah scrolls are stored in the holiest part of the synagogue in the Ark known as the "Holy Ark" (אֲרוֹן הקֹדשׁ aron hakodesh in Hebrew.) Aron in Hebrew means "cupboard" or "closet", and kodesh is derived from "kadosh", or "holy".

Torah translations

[edit]

Aramaic

[edit]The Book of Ezra refers to translations and commentaries of the Hebrew text into Aramaic, the more commonly understood language of the time. These translations would seem to date to the 6th century BCE. The Aramaic term for translation is Targum.[85] The Encyclopaedia Judaica has:

However, there is no suggestion that these translations had been written down as early as this. There are suggestions that the Targum was written down at an early date, although for private use only.

Greek

[edit]One of the earliest known translations of the first five books of Moses from the Hebrew into Greek was the Septuagint. This is a Koine Greek version of the Hebrew Bible that was used by Greek speakers. This Greek version of the Hebrew Scriptures dates from the 3rd century BCE, originally associated with Hellenistic Judaism. It contains both a translation of the Hebrew and additional and variant material.[88]

Later translations into Greek include seven or more other versions. These do not survive, except as fragments, and include those by Aquila, Symmachus, and Theodotion.[89]

Latin

[edit]Early translations into Latin—the Vetus Latina—were ad hoc conversions of parts of the Septuagint. With Saint Jerome in the 4th century CE came the Vulgate Latin translation of the Hebrew Bible.[90]

Arabic

[edit]From the eighth century CE, the cultural language of Jews living under Islamic rule became Arabic rather than Aramaic. "Around that time, both scholars and lay people started producing translations of the Bible into Judeo-Arabic using the Hebrew alphabet." Later, by the 10th century, it became essential for a standard version of the Bible in Judeo-Arabic. The best known was produced by Saadiah (the Saadia Gaon, aka the Rasag), and continues to be in use today, "in particular among Yemenite Jewry".[91]

Rav Sa'adia produced an Arabic translation of the Torah known as Targum Tafsir and offered comments on Rasag's work.[92] There is a debate in scholarship whether Rasag wrote the first Arabic translation of the Torah.[93]

Modern languages

[edit]Jewish translations

[edit]The Torah has been translated by Jewish scholars into most of the major European languages, including English, German, Russian, French, Spanish and others. The most well-known German-language translation was produced by Samson Raphael Hirsch. A number of Jewish English Bible translations have been published, for example by Artscroll publications.[94]

Christian translations

[edit]As a part of the Christian biblical canons, the Torah has been translated into hundreds of languages.

In other religions

[edit]Samaritanism

[edit]

The Samaritan Torah (ࠕࠫࠅࠓࠡࠄ, Tōrāʾ), also called the Samaritan Pentateuch, is the scripture of Samaritanism, which is slightly different from the Torah of Judaism. The Samaritan Pentateuch was written in the Samaritan script, a direct descendant of the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet that emerged around 600 BCE. Some 6,000 differences exist between the Samaritan and Jewish Masoretic Text, most of which are minor spelling and grammar variations, while others involve significant semantic changes, such as the uniquely Samaritan commandment to construct an altar on Mount Gerizim.[95] Nearly 2,000 textual variations are found to be consistent with the Koine Greek[96] Septuagint, some with the Latin Vulgate.[97] It is reported that Samaritans translated their Pentateuch into Aramaic, Greek and Arabic.[98]

Christianity

[edit]Although different Christian denominations have slightly different versions of the Old Testament in their Bibles, the Torah as the "Five Books of Moses" (or "the Mosaic Law") is common among them all.

Islam

[edit]Islam states that the Torah was sent by God. The "Tawrat" (Arabic: توراة) is the Arabic name for the Torah within its context as an Islamic holy book believed by Muslims to be given by God to Prophets among the Children of Israel, and often refers to the entire Hebrew Bible.[10] According to the Quran, God says, "It is He Who has sent down the Book (the Quran) to you with truth, confirming what came before it. And He sent down the Taurat (Torah) and the Injeel (Gospel)." (Q3:3) However, the Muslims believe that this original revelation was corrupted (tahrif) (or simply altered by the passage of time and human fallibility) over time by Jewish scribes.[99] The Torah in the Quran is always mentioned with respect in Islam. The Muslims' belief in the Torah, as well as the prophethood of Moses, is one of the fundamental tenets of Islam.

The Islamic methodology of tafsir al-Qur'an bi-l-Kitab (Arabic: تفسير القرآن بالكتاب) refers to interpreting the Qur'an with/through the Bible.[100] This approach adopts canonical Arabic versions of the Bible, including the Torah, both to illuminate and to add exegetical depth to the reading of the Qur'an. Notable Muslim mufassirun (commentators) of the Bible and Qur'an who weaved from the Torah together with Qur'anic ones include Abu al-Hakam Abd al-Salam bin al-Isbili of Al-Andalus and Ibrahim bin Umar bin Hasan al-Biqa'i.[100]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Torah". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 September 2024. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Torah | Definition, Meaning, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ^ a b c Birnbaum 1979, p. 630.

- ^ Vol. 11 Trumah Section 61

- ^ Blenkinsopp 1992, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d McDermott 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Schniedewind 2022, p. 23.

- ^ Schmid, Konrad; Lackowski, Mark; Bautch, Richard. "How to Identify a Persian Period Text in the Pentateuch". R. J. Bautch / M. Lackowski (eds.), On Dating Biblical Texts to the Persian Period, FAT II/101, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2019, 101–118. "There are, however, a few exceptions regarding the pre-Hellenistic dating of the Pentateuch. The best candidate for a post-Persian, Hellenistic text in the Pentateuch seems to be the small 'apocalypse' in Num 24:14-24, which in v. 24 mentions the victory of the ships of the כִּתִּים over Ashur and Eber. This text seems to allude to the battles between Alexander and the Persians, as some scholars suggested. Another set of post-Persian text elements might be the specific numbers in the genealogies of Gen 5 and 11. These numbers build the overall chronology of the Pentateuch and differ significantly in the various versions. But these are just minor elements. The substance of the Pentateuch seems pre- Hellenistic."

- ^ Römer, Thomas "How "Persian" or "Hellenistic" is the Joseph Narrative?", in T. Römer, K. Schmid et A. Bühler (ed.), The Joseph Story Between Egypt and Israel (Archaeology and Bible 5), Tübinngen: Mohr Siebeck, 2021, pp. 35-53. "The date of the original narrative can be the late Persian period, and while there are several passages that fit better into a Greek, Ptolemaic context, most of these passages belong to later revisions."

- ^ a b c Lang 2015, p. 98.

- ^ cf. Lev 10:11

- ^ Rabinowitz, Louis; Harvey, Warren (2007). "Torah". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 20 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. pp. 39–46. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- ^ Alcalay (1996), p. 2767.

- ^ Scherman 2001, pp. 164–165, Exodus 12:49.

- ^ "Torah | Definition, Meaning, & Facts | Britannica". 28 December 2023.

- ^ Joshua 8:31–32; 23:6

- ^ I Kings 2:3; II Kings 14:6; 23:25

- ^ Malachi 3:22; Daniel 9:11, 13; Ezra 3:2; 7:6; Nehemiah 8:1; II Chronicles 23:18; 30:16

- ^ Ezra 6:18; Neh. 13:1; II Chronicles 35:12; 25:4; cf. II Kings 14:6

- ^ Nehemiah 8:3

- ^ Nehemiah 8:8, 18; 10:29–30; cf. 9:3

- ^ Sarna, Nahum M.; et al. (2007). "Bible". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. pp. 576–577. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- ^ Merrill, Rooker & Grisanti 2011, p. 163, Part 4. The Pentateuch by Michael A. Grisanti: "The Term 'Pentateuch' derives from the Greek pentateuchos, literally, ... The Greek term was apparently popularized by the Hellenized Jews of Alexandria, Egypt, in the first century AD..."

- ^ Pattanaik, David (9 July 2017). "The Fascinating Design Of The Jewish Bible". Mid-Day. Mumbai.

- ^ Hamilton 1990, p. 1.

- ^ Bergant 2013, p. xii.

- ^ Bandstra 2008, p. 35.

- ^ Bandstra 2008, p. 78.

- ^ Bandstra 2004, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Johnstone 2003, p. 72.

- ^ Finkelstein & Silberman 2002, p. 68.

- ^ Meyers 2005, p. xv.

- ^ Ashley 1993, p. 1.

- ^ Olson 1996, p. 9.

- ^ Stubbs 2009, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Phillips 1973, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Rogerson 2003, pp. 153–154.

- ^ Sommer 2015, p. 18.

- ^ Deuteronomy 6:4

- ^ Mark 12:28–34

- ^ Bava Basra 14b

- ^ Mishnah, Sanhedrin 10:1

- ^ Talmud Gitten 60a,

- ^ language of Maimonides, Commentary on the Mishnah, Sanhedrin 10:1

- ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews Vol. IV: Ezra (Translated by Henrietta Szold) Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society.

- ^ Ross 2004, p. 192.

- ^ Sanhedrin 21b

- ^ Commentary on the Talmud, Sanhedrin 21b

- ^ Carr 2014, p. 434.

- ^ Thompson 2000, p. 8.

- ^ Ska 2014, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Van Seters 2004, p. 77.

- ^ Baden 2012.

- ^ a b Gaines 2015, p. 271.

- ^ Otto 2014, p. 605.

- ^ Grabbe, Lester (2017). Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How Do We Know It?. T&T Clark. p. 249-250. "It was once conventional to accept Josiah's reform at face value, but the question is currently much debated (Albertz 1994: 198–201; 2005; Lohfink 1995; P. R. Davies 2005; Knauf 2005a)."

- ^ Pakkala, Juha (2010). "Why the Cult Reforms In Judah Probably Did Not Happen". In Kratz, Reinhard G.; Spieckermann, Hermann (eds.). One God – One Cult – One Nation. De Gruyter. pp. 201–235. ISBN 9783110223576. Retrieved 2024-01-25 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ Hess, Richard S. (2022). "2 Kings 22-3: Belief in One God in Preexilic Judah?". In Watson, Rebecca S.; Curtis, Adrian H. W. (eds.). Conversations on Canaanite and Biblical Themes: Creation, Chaos and Monotheism. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 135–150. ISBN 978-3-11-060629-4.

- ^ Carr 2014, p. 457.

- ^ Otto 2014, p. 609.

- ^ Frei 2001, p. 6.

- ^ Romer 2008, p. 2 and fn.3.

- ^ Ska 2006, p. 217.

- ^ Ska 2006, p. 218.

- ^ Eskenazi 2009, p. 86.

- ^ Ska 2006, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Greifenhagen 2003, pp. 206–207, 224 fn.49.

- ^ Gmirkin 2006, pp. 30, 32, 190.

- ^ Wellhausen 1885, pp. 405–410.

- ^ Wellhausen 1885, p. 408 n. 1.

- ^ Adler 2022.

- ^ Adler 2022, pp. 223–234.

- ^ Collins, John J. (2022). "The Torah in its Symbolic and Prescriptive Functions". Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel. 11 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1628/hebai-2022-0003 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 2192-2276.

- ^ Spiro, Ken (9 May 2009). "History Crash Course #36: Timeline: From Abraham to Destruction of the Temple". Aish.com. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- ^ Berlin, Brettler & Fishbane 2004, pp. 3–7.

- ^ For more information on these issues from an Orthodox Jewish perspective, see Modern Scholarship in the Study of Torah: Contributions and Limitations, Ed. Shalom Carmy, and Handbook of Jewish Thought, Volume I, by Aryeh Kaplan.

- ^ Siekawitch 2013, pp. 19–30.

- ^ Neh. 8

- ^ Rogovin, Richard D. (2006). "The Authentic Triennial Cycle: A Better Way to Read Torah?". United Synagogue Review. 59 (1). Archived from the original on 6 September 2009 – via The United Synagoue of Conservative Judaism.

- ^ Fields, Harvey J. (1979). "Section Four: The Reading of the Torah". Bechol Levavcha: with all your heart. New York: Union of American Hebrew Congregations Press. pp. 106–111. Archived from the original on 19 February 2005 – via Union for Reform Judaism.

- ^ "Rabbi Jonathan Rietti | New York City | Breakthrough Chinuch". breakthroughchunich.

- ^ Talmud, Gittin 60b

- ^ "FAQ for Humanistic Judaism, Reform Judaism, Humanists, Humanistic Jews, Congregation, Arizona, AZ". Oradam.org. Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- ^ Mishnat Soferim The forms of the letters Archived 2008-05-23 at the Wayback Machine translated by Jen Taylor Friedman (geniza.net)

- ^ Chilton 1987, p. xiii.

- ^ Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred, eds. (2007). "Torah, Reading of". Encyclopaedia Judaica (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- ^ Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred, eds. (2007). "Bible: Translations". Encyclopaedia Judaica (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- ^ Greifenhagen 2003, p. 218.

- ^ Greenspoon, Leonard J. (2007). "Greek: The Septuagint". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. p. 597. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- ^ Harkins, Franklin T.; Harkins, Angela Kim (2007). "Old Latin/Vulgate". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. p. 598. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- ^ Sasson, Ilana (2007). "Arabic". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. p. 603. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4.

- ^ Robinson 2008, pp. 167–: "Sa'adia's own major contribution to the Torah is his Arabic translation, Targum Tafsir."

- ^ Zohar 2005, pp. 106–: "Controversy exists among scholars as to whether Rasag was the first to translate the Hebrew Bible into Arabic."

- ^ Greenspoon, Leonard J. (2020). "Jewish Bible Translations: Personalities, Passions, Politics,Progress" (DOCX). Jewish Publication Society.

- ^ Giles, Terry; T. Anderson, Robert (2012). The Samaritan Pentateuch: an introduction to its origin, history, and significance for Biblical studies. Resources for Biblical Study. Society of Biblical Literature. doi:10.2307/j.ctt32bzhn. ISBN 978-1-58983-699-0. JSTOR j.ctt32bzhn.

- ^ The common supra-regional form of Greek used during the Hellenistic period, the eras of the Roman Empire and early Byzantine Empire.

- ^ A late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bible.

- ^ Florentin, Moshe (2013). "Samaritan Pentateuch". In Khan, Geoffrey; Bolozky, Shmuel; Fassberg, Steven; Rendsburg, Gary A.; Rubin, Aaron D.; Schwarzwald, Ora R.; Zewi, Tamar (eds.). Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/2212-4241_ehll_EHLL_COM_00000282. ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3.

- ^ Is the Bible God's Word Archived 2008-05-13 at the Wayback Machine by Sheikh Ahmed Deedat

- ^ a b McCoy 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adler, Yonatan (2022). The Origins of Judaism: An Archaeological-Historical Reappraisal. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300254907.

- Alcalay, Reuben (1996). The Complete Hebrew – English dictionary. Vol. 2. New York: Hemed Books. ISBN 978-965-448-179-3.

- Ashley, Timothy R. (1993). The Book of Numbers. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802825230.

- Baden, Joel S. (2012). The Composition of the Pentateuch: Renewing the Documentary Hypothesis. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300152647.

- Bandstra, Barry L. (2004). Reading the Old Testament: an introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth. ISBN 9780495391050.

- Bandstra, Barry L. (2008). Reading the Old Testament. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0495391050.

- Bergant, Dianne (2013). Genesis: In the Beginning. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0814682753.

- Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Fishbane, Michael, eds. (2004). The Jewish Study Bible. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195297515.

- Birnbaum, Philip (1979). Encyclopedia of Jewish Concepts. Wadsworth.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (1992). The Pentateuch: An introduction to the first five books of the Bible. Anchor Bible Reference Library. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-41207-0.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2004). Treasures old and new: essays in the theology of the Pentateuch. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802826794.

- Campbell, Antony F; O'Brien, Mark A (1993). Sources of the Pentateuch: texts, introductions, annotations. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451413670.

- Carr, David M (1996). Reading the fractures of Genesis. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664220716.

- Carr, David M. (2014). "Changes in Pentateuchal Criticism". In Sæbø, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Chilton, B.D., ed. (1987). The Isaiah Targum: Introduction, Translation, Apparatus and Notes. Michael Glazier, Inc.

- Clines, David A (1997). The theme of the Pentateuch. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780567431967.

- Davies, G.I (1998). "Introduction to the Pentateuch". In John Barton (ed.). Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198755005.

- Eskenazi, Tamara Cohn (2009). "From Exile and Restoration to Exile and Reconstruction". In Grabbe, Lester L.; Knoppers, Gary N. (eds.). Exile and Restoration Revisited: Essays on the Babylonian and Persian Periods. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780567465672.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743223386.

- Frei, Peter (2001). "Persian Imperial Authorization: A Summary". In Watts, James (ed.). Persia and Torah: The Theory of Imperial Authorization of the Pentateuch. Atlanta, GA: SBL Press. p. 6. ISBN 9781589830158.

- Friedman, Richard Elliot (2001). Commentary on the Torah With a New English Translation. Harper Collins Publishers.

- Gaines, Jason M.H. (2015). The Poetic Priestly Source. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-5064-0046-4.

- Gmirkin, Russell (2006). Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-13439-4.

- Gooder, Paula (2000). The Pentateuch: a story of beginnings. T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567084187.

- Greifenhagen, Franz V. (2003). Egypt on the Pentateuch's Ideological Map. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-39136-0.

- Hamilton, Victor P. (1990). The Book of Genesis: chapters 1–17. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802825216.

- Jacobs, Louis (1995). The Jewish Religion: a companion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-826463-7. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- Johnstone, William D. (2003). "Exodus". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Bible Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Kugler, Robert; Hartin, Patrick (2009). An Introduction to the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802846365.

- Lang, Isabel (31 December 2015). Intertextualität als hermeneutischer Zugang zur Auslegung des Korans: Eine Betrachtung am Beispiel der Verwendung von Israiliyyat in der Rezeption der Davidserzählung in Sure 38: 21–25 (in German). Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH. ISBN 9783832541514.

- Levin, Christoph L (2005). The Old testament: a brief introduction. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691113944.

- McCoy, R. Michael (2021-09-08). Interpreting the Qurʾān with the Bible (Tafsīr al-Qurʾān bi-l-Kitāb). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-46682-1.

- McDermott, John J. (2002). Reading the Pentateuch: a historical introduction. Pauline Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-4082-4. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- McEntire, Mark (2008). Struggling with God: An Introduction to the Pentateuch. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780881461015.

- Meyers, Carol (2005). Exodus. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521002912.

- Merrill, Eugene H.; Rooker, Mark; Grisanti, Michael A., eds. (2011). The World and the Word: An Introduction to the Old Testament.

- Nadler, Steven (2008). "The Bible Hermeneutics of Baruch de Spinoza". In Sæbø, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament: The History of its Interpretation, II: From the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3525539828. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- Neusner, Jacob (2004). The Emergence of Judaism. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

- Olson, Dennis T (1996). Numbers. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664237363.

- Otto, Eckart (2014). "The Study of Law and Ethics in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament". In Sæbø, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Phillips, Anthony (1973). Deuteronomy. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780521097727.

- Robinson, George (17 December 2008). Essential Torah: A Complete Guide to the Five Books of Moses. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-48437-6.

- Rogerson, John W. (2003). "Deuteronomy". In James D. G. Dunn; John William Rogerson (eds.). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Romer, Thomas (2008). "Moses Outside the Torah and the Construction of a Diaspora Identity" (PDF). Journal of Hebrew Scriptures. 8, article 15: 2–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-10-21. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- Ross, Tamar (2004). Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism. UPNE. p. 192.

- Scherman, Nosson, ed. (2001). Tanakh, Vol. I, The Torah (Stone ed.). New York: Mesorah Publications, Ltd.

- Schniedewind, William M. (2022). "Diversity and Development of tôrâ in the Hebrew Bible". In Schniedewind, William M.; Zurawski, Jason M.; Boccaccini, Gabriele (eds.). Torah: Functions, Meanings, and Diverse Manifestations in Early Judaism and Christianity. SBL Press. ISBN 978-1-62837-504-6.

- Siekawitch, Larry (2013). The Uniqueness of the Bible. Cross Books. ISBN 9781462732623.

- Ska, Jean-Louis (2006). Introduction to reading the Pentateuch. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061221.

- Ska, Jean Louis (2014). "Questions of the 'History of Israel' in Recent Research". In Sæbø, Magne; Ska, Jean Louis; Machinist, Peter (eds.). Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. III: From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Part II: The Twentieth Century – From Modernism to Post-Modernism. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-54022-0.

- Sommer, Benjamin D. (30 June 2015). Revelation and Authority: Sinai in Jewish Scripture and Tradition. Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library.

- Stubbs, David L (2009). Numbers (Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible). Brazos Press. ISBN 9781441207197.

- Thompson, Thomas L. (2000). Early History of the Israelite People: From the Written & Archaeological Sources. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004119437.

- Van Seters, John (1998). "The Pentateuch". In Steven L. McKenzie, Matt Patrick Graham (ed.). The Hebrew Bible today: an introduction to critical issues. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256524.

- Van Seters, John (2004). The Pentateuch: a social-science commentary. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780567080882.

- Walsh, Jerome T (2001). Style and structure in Biblical Hebrew narrative. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658970.

- Wellhausen, Julius (1885). Prolegomena to the History of Israel. Black. ISBN 9781606202050.

- Zohar, Zion (June 2005). Sephardic and Mizrahi Jewry: From the Golden Age of Spain to Modern Times. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9705-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Adler, Yonatan (16 February 2023). "When Did Jews Start Observing Torah? – TheTorah.com". thetorah.com. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- Rothenberg, Naftali, (ed.), Wisdom by the week – the Weekly Torah Portion as an Inspiration for Thought and Creativity, Yeshiva University Press, New York 2012

- Friedman, Richard Elliott, Who Wrote the Bible?, HarperSanFrancisco, 1997

- Welhausen, Julius, Prolegomena to the History of Israel, Scholars Press, 1994 (reprint of 1885)

- Kantor, Mattis, The Jewish time line encyclopedia: A year-by-year history from Creation to the present, Jason Aronson Inc., London, 1992

- Wheeler, Brannon M., Moses in the Quran and Islamic Exegesis, Routledge, 2002

- DeSilva, David Arthur, An Introduction to the New Testament: Contexts, Methods & Ministry, InterVarsity Press, 2004

- Heschel, Abraham Joshua, Tucker, Gordon & Levin, Leonard, Heavenly Torah: As Refracted Through the Generations, London, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2005

- Hubbard, David "The Literary Sources of the Kebra Nagast" Ph.D. dissertation St Andrews University, Scotland, 1956

- Peterson, Eugene H., Praying With Moses: A Year of Daily Prayers and Reflections on the Words and Actions of Moses, HarperCollins, New York, 1994 ISBN 9780060665180

888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888

The Book of Sirach (/ˈsaɪræk/)[a], also known as The Wisdom of Jesus the Son of Sirach[1] or Ecclesiasticus (/ɪˌkliːziˈæstɪkəs/),[2] is a Jewish literary work, originally written in Biblical Hebrew. The longest extant wisdom book from antiquity,[1][3] it consists of ethical teachings, written approximately between 196 and 175 BCE by Yeshua ben Eleazar ben Sira (Ben Sira), a Hellenistic Jewish scribe of the Second Temple period.[1][4]

Ben Sira's grandson translated the text into Koine Greek and added a prologue sometime around 117 BCE.[3] This prologue is generally considered to be the earliest witness to a tripartite canon of the books of the Old Testament[5] and thus the date of the text is the subject of intense scrutiny by biblical scholars. The ability to precisely date the composition of Sirach within a few years provides great insight into the historical development and evolution of the Jewish canon. Although the Book of Sirach is not included in the Hebrew Bible, it is included in the Septuagint.

Authorship

[edit]

Yeshua ben Eleazar ben Sira (Ben Sira, or—according to the Greek text—"Jesus the son of Sirach of Jerusalem") was a Hellenistic Jewish scribe of the Second Temple period. He wrote the Book of Sirach in Biblical Hebrew around 180 BCE.[3] Among all Old Testament and apocryphal writers, Ben Sira is unique in that he is the only one to have claimed authorship of his work.[1]

Date and historical setting

[edit]The Book of Sirach is generally dated to the first quarter of the 2nd century BCE. The text refers in the past tense to "the high priest, Simon son of Onias" (chapter 50:1). This passage almost certainly refers to Simon the High Priest, the son of Onias II, who died in 196 BCE. Because the struggles between Simon's successors (Onias III, Jason, and Menelaus) are not alluded to in the book, nor is the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes (who acceded to the throne in 175 BCE), the book must therefore have been written between 196 and 175 BCE.[4]

Translation into Koine Greek

[edit]The person who translated the Book of Sirach into Koine Greek states in his prologue that he was the grandson of the author, and that he came to Egypt (most likely Alexandria) in the thirty-eighth year of the reign of "Euergetes".[3] This epithet was borne by only two of the Ptolemaic kings. Of these, Ptolemy III Euergetes reigned only twenty-five years (247–222 BCE), and thus Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II must be intended. Since this king dated his reign from the date of his first ascension to the throne in the year 170 BCE, the translator must therefore have gone to Egypt in 132 BCE. Ben Sira's grandson completed his translation and added the prologue circa 117 BCE, around the time of the death of Ptolemy VIII.[3] At that time, the usurping Hasmonean dynasty had ousted the heirs of Simon II after long struggles and was finally in control of the High Priesthood. A comparison of the Hebrew and Greek versions shows that he altered the prayer for Simon and broadened its application ("may He entrust to us his mercy") to avoid closing a work praising God's covenanted faithfulness on an unanswered prayer.[6]

The Greek version of the Book of Sirach is found in many codices of the Septuagint.[7]

Alternative titles

[edit]The Koine Greek translation was accepted in the Septuagint under the abbreviated name of the author: Sirakh (Σιραχ). Some Greek manuscripts give as the title the "Wisdom of Iēsous Son of Sirakh" or in short the "Wisdom of Sirakh". The Old Latin Bible was based on the Septuagint, and simply transliterated the Greek title into Latin letters: Sirach. In the Latin Vulgate, the book is called Sapientia Jesu Filii Sirach ("The Wisdom of Jesus the Son of Sirach").

The Greek Church Fathers also called it the "All-Virtuous Wisdom", while the Latin Church Fathers, beginning with Cyprian,[8] termed it Ecclesiasticus because it was frequently read in churches, leading the Latin Church Fathers to call it Liber Ecclesiasticus ("Church Book"). Similarly, the New Latin Vulgate and many modern English translations of the Apocrypha use the title Ecclesiasticus, literally "of the Church" because of its frequent use in Christian teaching and worship.

Structure

[edit]As with other wisdom books, there is no easily recognizable structure in Sirach; in many parts it is difficult to discover a logical progression of thought or to discern the principles of arrangement.[3] However, a series of six poems about the search for and attainment of wisdom (1:1–10, 4:11–19; 6:18–37; 14:20–15:10; 24:1–33; and 38:24–39:11) divide the book into something resembling chapters, although the divisions are not thematically based.[3] The exceptions are the first two chapters, whose reflections on wisdom and fear of God provide the theological framework for what follows, and the last nine chapters, which function as a sort of climax, first in an extended praise of God's glory as manifested through creation (42:15–43:33) and second in the celebration of the heroes of ancient Israel's history dating back to before the Great Flood through contemporary times (see previous section).[3]

Despite the lack of structure, there are certain themes running through the book which reappear at various points. The New Oxford Annotated Apocrypha identifies ten major recurring topics:

- The Creation: 16:24–17:24; 18:1–14; 33:7–15; 39:12–35; and 42:15–43:33

- Death: 11:26–28; 22:11–12; 38:16–23; and 41:1–13

- Friendship: 6:5–17; 9:10–16; 19:13–17; 22:19–26; 27:16–21; and 36:23–37:15

- Happiness: 25:1–11; 30:14–25; and 40:1–30

- Honor and shame: 4:20–6:4; 10:19–11:6; and 41:14–42:8

- Money matters: 3:30–4:10; 11:7–28; 13:1–14:19; 29:1–28; and 31:1–11

- Sin: 7:1–17; 15:11–20; 16:1–17:32; 18:30–19:3; 21:1–10; 22:27–23:27; and 26:28–28:7

- Social justice: 4:1–10; 34:21–27; and 35:14–26

- Speech: 5:6, 9–15; 18:15–29; 19:4–17; 20:1–31; 23:7–15; 27:4–7, 11–15; and 28:8–26

- Women: (9:1–9; 23:22–27; 25:13–26:27; 36:26–31; and 42:9–14.[3][9]

Some scholars contend that verse 50:1 seems to have formed the original ending of the text, and that Chapters 50 (from verse 2) and 51 are later interpolations.[10]

Content

[edit]

The Book of Sirach is a collection of ethical teachings that closely resembles Proverbs, except that—unlike the latter—it is presented as the work of a single author and not as an anthology of maxims or aphorisms drawn from various sources. The teachings of the Book of Sirach are intended to apply to all people regardless of circumstances. Many of them are rules of courtesy and politeness, and they contain advice and instruction as to the duties of man toward himself and others, especially the poor and the oppressed, as well as toward society and the state, and most of all toward God. Wisdom, in Ben Sira's view, is synonymous with submission to the will of God, and sometimes is identified in the text with adherence to the Mosaic law. The question of which sayings originated with the Book of Sirach is open to debate, although scholars tend to regard Ben Sira as a compiler or anthologist.[3]

By contrast, the author exhibits little compassion for women and slaves. He advocates distrust of and possessiveness over women,[11] and the harsh treatment of slaves (which presupposes the validity of slavery as an institution),[12] positions which are not only difficult for modern readers, but cannot be completely reconciled with the social milieu at the time of its composition.

The Book of Sirach contains the only instance in a biblical text of explicit praise for physicians (chapter 38), though other biblical passages take for granted that medical treatment should be used when necessary.[13][14] This is a direct challenge against the idea that illness and disease were seen as penalties for sin, to be cured only by repentance.[15]

As in Ecclesiastes, the author exhibits two opposing tendencies: the faith and the morality of earlier times, and an Epicureanism of modern date. Occasionally Ben Sira digresses to attack theories that he considers dangerous; for example, that man has no freedom of will, and that God is indifferent to the actions of mankind and does not reward virtue. Some of the refutations of these views are developed at considerable length.

Throughout the text runs the prayer of Israel imploring God to gather together his scattered children, to bring to fulfillment the predictions of the Prophets, and to have mercy upon his Temple and his people. The book concludes with a justification of God, whose wisdom and greatness are said to be revealed in all God's works as well as in the history of Israel. The book ends with the author's attestation, followed by two hymns (chapter 51), the latter a sort of alphabetical acrostic.

Of particular interest to biblical scholars are Chapters 44–50, in which Ben Sira praises "famous men, our ancestors in their generations", starting from the antediluvian Enoch and continuing through to Simon, son of Onias (300–270 BCE). Within the text of these chapters, Ben Sira identifies, either directly or indirectly, each of the books of the Hebrew Bible that would eventually become canonical (all of the five books of the Torah, the eight books of the Nevi'im, and six of the eleven books of the Ketuvim). The only books that are not referenced are Ezra, Daniel, Ruth, Esther, and perhaps Chronicles.[16] The ability to date the composition of Sirach within a few years given the autobiographical hints of Ben Sira and his grandson (author of the introduction to the work) provides great insight regarding the historical development and evolution of the Jewish canon.[17]

Canonical status

[edit]

Judaism

[edit]Despite containing the oldest known list of Jewish canonical texts, the Book of Sirach itself is not part of the Jewish canon. Some authors suggest this is due to its late authorship,[3][18] although the canon was not yet closed at the time of Ben Sira.[19] For example, the Book of Daniel was included in the canon, despite the fact that its date of composition (between 168 and 164 BCE)[20][21][22] was later than that of the Book of Sirach. Others have suggested that Ben Sira's self-identification as the author precluded it from attaining canonical status, which was reserved for works that were attributed (or could be attributed) to the prophets,[23] or that it was denied entry to the canon as a rabbinical counter-reaction to its embrace by the nascent Christian community.[24]

Christianity

[edit]The Book of Sirach is accepted as part of the canon by Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox Christians. It was cited in some writings in early Christianity. Clement of Alexandria and Origen quote from it repeatedly, as from a γραφή (Scripture).[1]

Augustine of Hippo[25] (c. 397), Pope Innocent I (405),[26] the Council of Rome (382 AD),[27][28] the Synod of Hippo (in 393),[29] followed by the Council of Carthage (397), the Council of Carthage (419)[30] Quinisext Council (692), and the Council of Florence (1442)[31] all regarded it as a canonical book, although Jerome, Rufinus of Aquileia and the Council of Laodicea ranked it instead as an ecclesiastical book.[1] In the 4th and 5th centuries, the Church Fathers recommended the Book of Sirach among other deuterocanonical books for edification and instruction.[32] The Apostolic Canons (recognized by the Eastern Orthodox Church during the 5th and 6th centuries) also described "the Wisdom of the very learned Sirach" as a recommended text for teaching young people.[33][28] The Catholic Church then reaffirmed The Book of Sirach and the other deuterocanonical books in 1546 during the fourth session of the Council of Trent, and attached an excommunication to the denial of their scriptural status.[1][34] Catholic canonical recognition only extends to the Greek text.[35]

Because it was excluded from the Jewish canon, the Book of Sirach was not counted as being canonical in Christian denominations originating from the Protestant Reformation, although some retained the book in an appendix to the Bible called "Apocrypha". The Anglican tradition considers the book (which was published with other Greek Jewish books in a separate section of the King James Bible) among the biblical apocrypha as deuterocanonical books, and reads them "for example of life and instruction of manners; but yet [does] not apply them to establish any doctrine".[36] The Lutheran Churches take a similar position.

Manuscripts

[edit]

The Book of Sirach was originally written in Biblical Hebrew and was also known as the "Proverbs of ben Sira" (משלי בן סירא, Mišlē ben Sirā) or the "Wisdom of ben Sira" (חכמת בן סירא, Ḥokhmat ben Sirā). The book was not accepted into the Hebrew Bible and the original Hebrew text was not preserved by the Masoretes. However, in 1896, several scroll fragments of the original Hebrew texts of the Book of Sirach, copied in the 11th and 12th centuries, were found in the Cairo Geniza (a synagogue storage room for damaged manuscripts).[37][38][39] Although none of these manuscripts are complete, together they provide the text for about two-thirds of the Book of Sirach.[40] According to scholars including Solomon Schechter and Frederic G. Kenyon, these findings support the assertion that the book was originally written in Hebrew.[41]

In the 1950s and 1960s, three fragments of parchment scrolls of the Book of Sirach written in Hebrew were discovered near the Dead Sea. The largest scroll, Mas1H (MasSir), was discovered in casemate room 1109 at Masada, the Jewish fortress destroyed by the Romans in 73 CE.[42][43] This scroll contains Sirach 39:27–44:17.[44] The other two scroll fragments were found at Qumran. One of these, the Great Psalms Scroll (11Q5 or 11QPsa), contains Sirach chapter 51 (verses 13-20, and 30).[45] The other fragment, 2Q18 (2QSir), contains Sirach 6:14–15, 20–31. These early Hebrew texts are in substantial agreement with the Hebrew texts discovered in Cairo, although there are numerous minor textual variants. With these findings, scholars are now more confident that the Cairo texts are reliable witnesses to the Hebrew original.[46][47]

Theological significance

[edit]Influence in Jewish doctrine and liturgy

[edit]

Although excluded from the Jewish canon, the Book of Sirach was well-known among Jews during the late Second Temple period. The Greek translation made by Ben Sira's grandson was included in the Septuagint (the 2nd-century BCE Greek version of the Hebrew Bible), which became the foundation of the early Christian canon.[42] Furthermore, the many manuscript fragments discovered in the Cairo Genizah evince its authoritative status among Egyptian Jewry until well into the Middle Ages.[18]

The Book of Sirach was read and quoted as authoritative from the beginning of the rabbinic period. The Babylonian Talmud and other works of rabbinic literature occasionally paraphrase Ben Sira (e.g., Sanhedrin 100b, Hagigah 13a, Bava Batra 98b, Niddah 16b, etc.), but it does not mention his name. These quotes found in the Talmud correspond very closely to those found in the three scroll fragments of the Hebrew version of the Book of Sirach found at Qumran. Tractate Sanhedrin 100b records an unresolved debate between R'Joseph and Abaye as to whether it is forbidden to read the Book of Sirach, wherein Abaye repeatedly draws parallels between statements in Sirach cited by R'Joseph as objectionable and similar statements appearing in canonical books.[48]

The Book of Sirach may have been used as a basis for two important parts of the Jewish liturgy. In the Mahzor (High Holiday prayer book), a medieval Jewish poet may have used the Book of Sirach as the basis for a poem, Mar'e Kohen, in the Yom Kippur musaf ("additional") service for the High Holidays.[49] Yosef Tabori questioned whether this passage in the Book of Sirach is referring at all to Yom Kippur, and thus argued it cannot form the basis of this poem.[50] Some early 20th-century scholars also argued that the vocabulary and framework used by the Book of Sirach formed the basis of the most important of all Jewish prayers, the Amidah, but that conclusion is disputed as well.[51]

Current scholarship takes a more conservative approach. On one hand, scholars find that "Ben Sira links Torah and wisdom with prayer in a manner that calls to mind the later views of the Rabbis", and that the Jewish liturgy echoes the Book of Sirach in the "use of hymns of praise, supplicatory prayers and benedictions, as well as the occurrence of [Biblical] words and phrases [that] take on special forms and meanings."[52] However, they stop short of concluding a direct relationship existed; rather, what "seems likely is that the Rabbis ultimately borrowed extensively from the kinds of circles which produced Ben Sira and the Dead Sea Scrolls ....".[52]

Influence in Christian doctrine

[edit]Some of the earliest Christian writings, including those of the Apostolic Fathers, reference the Book of Sirach. For example, Didache 4:7[53] and Barnabas 19:9[54] both appear to reference Sirach 4:31.[18] Although the Book of Sirach is not quoted directly, there are many apparent references to it in the New Testament.[42][55] For example:

- in Matthew 6:7, Jesus said "But when ye pray, use not vain repetitions", where Sirach has "Do not babble in the assembly of the elders, and do not repeat yourself when you pray".(Sirach 7:14)

- Matthew 6:12 has "And forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors", where Sirach has "Forgive your neighbor a wrong, and then, when you petition, your sins will be pardoned" (Sirach 28:2)

- in Matthew 7:16, Jesus said "Ye shall know them by their fruits. Do men gather grapes of thorns, or figs of thistles?", where Sirach has "Its fruit discloses the cultivation of a tree" (Sirach 27:6) [56]

- in Matthew 11:28, Jesus said "Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest", where Sirach has "See with your own eyes that I have laboured but little and found for myself much serenity." (Sirach 51:27)

- Mark 4:5 has "Other seed fell on shallow soil with underlying rock. The seed sprouted quickly because the soil was shallow",[57] where Sirach has "The children of the ungodly won't grow many branches, and are as unhealthy roots on a sheer rock." (Sirach 40:15)

- Luke 1:52 has "He has put down the mighty from their thrones, and exalted the lowly",[58] where Sirach has "The Lord overthrows the thrones of rulers, and enthrones the lowly in their place." (Sirach 10:14)

- in Acts 20:35, Paul the Apostle said "It is more blessed to give than to receive", whereas Sirach has "Do not let your hand be stretched out to receive and closed when it is time to give" (Sirach 4:31)

- James 1:19 has "Wherefore, my beloved brethren, let every man be swift to hear, slow to speak, slow to wrath",[59] where Sirach has "Be quick to hear, but deliberate in answering." (Sirach 5:11)

Messianic interpretation by Christians

[edit]

Some Christians[who?] regard the catalogue of famous men in the Book of Sirach as containing several messianic references. The first occurs during the verses on David. Sirach 47:11 reads "The Lord took away his sins, and exalted his power for ever; he gave him the covenant of kings and a throne of glory in Israel." This references the covenant of 2 Samuel 7, which pointed toward the Messiah. "Power" (Hebrew qeren) is literally translated as 'horn'. This word is often used in a messianic and Davidic sense (e.g. Ezekiel 29:21, Psalms 132:17, Zechariah 6:12, Jeremiah 33:15). It is also used in the Benedictus to refer to Jesus ("and has raised up a horn of salvation for us in the house of his servant David").[60]

Another verse (47:22) that Christians interpret messianically begins by again referencing 2 Samuel 7. This verse speaks of Solomon and goes on to say that David's line will continue forever. The verse ends stating that "he gave a remnant to Jacob, and to David a root of his stock". This references Isaiah's prophecy of the Messiah: "There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of his roots"; and "In that day the root of Jesse shall stand as an ensign to the peoples; him shall the nations seek…" (Isaiah 11:1, 10).[61]

References in the Book of Sirach and pre-modern texts

[edit]Note: verse numbers may vary slightly between versions.

- Aesop's fable of The Two Pots is referenced at Sirach 13:2–3[62][63]